Bangladesh's Attorney General, Md Asaduzzaman, has stirred up controversy by suggesting changes to the country's constitution. Asaduzzaman proposed removing terms such as socialism, secularism, Bengali nationalism, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's title as "Father of the Nation".

Asaduzzaman made these arguments during High Court hearings on the 15th Constitutional Amendment's legality on Wednesday. The amendment, passed in 2011 increased the number of reserved seats for women in parliament from 45 to 50 and reinstated secularism and religious freedom in the constitution. It also recognised Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the Father of the Nation.

Also Read | The Hindu Question In Bangladesh

Asaduzzaman argued these concepts no longer reflect Bangladesh's current state, particularly given its large Muslim population. According to the 2022 national government census, Muslims constitute approximately 91 per cent of the population. This proposal has revived the debate about Bangladesh's identity and the role of religion in governance.

This is not the first time the term secularism is being questioned in Bangladesh. The South Asian country first adopted secularism as a core principle in its constitution in 1972. However, the term was removed in 1977 by a Martial Law directive during the military dictatorship of Ziaur Rahman.

In 1988, Parliament designated Islam the state religion, and subsequent governments have retained this designation. In 2010, the Bangladesh Supreme Court ruled that the removal of secularism in 1977 was illegal since it was done by an unconstitutional martial law regime. The court reinstated secularism in the constitution.

Countries Struggle To Balance Religion And Politics

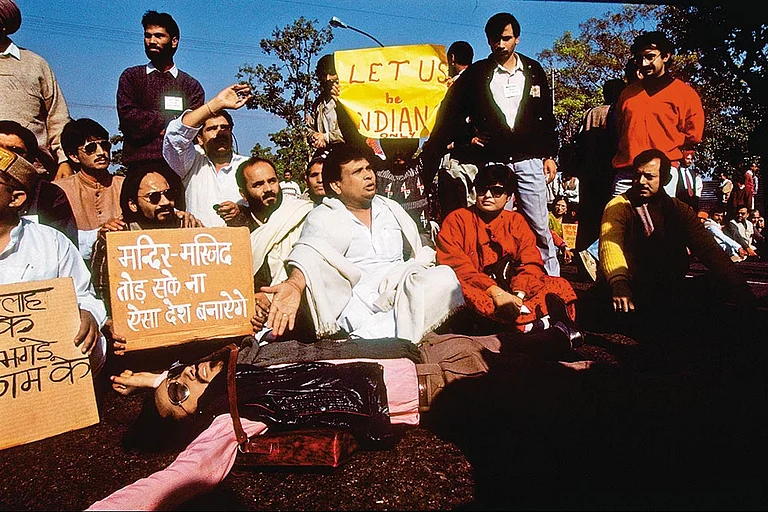

The boundary between religion and secular life is a contentious issue around the world, with various countries struggling to find a balance. In India, for instance, there's been a growing push from right-wing groups to establish India as a Hindu nation, enshrining Hindu supremacy in law.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban's 2021 takeover led to the institution of strict Qur'anic interpretations and the conversion of secular schools and universities into Islamic seminaries.

Also Read | Hindutva Ideology: A Challenge to Stay Relevant in 2024

Similarly, Europe faces its own secularism-related challenges, particularly with the rise of multiculturalism and immigration. This can be seen in the banning of Islamic clothing, kosher or halal meals and “burkinis” in France.

The backlash against migrants following the UK's decision to leave the EU and the rejection of former German Chancellor Angela Merkel's pro-migration policy by a portion of the German population are both indicators of this struggle.

Similarly, Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan has pushed to mainstream Islam in politics during his 17-year tenure. In 2020, he redesignated Istanbul's Hagia Sophia as a mosque, fulfilling his long-held ambition. The sixth-century building was converted into a museum in the early days of the modern secular Turkish state under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

The influence of ultra-Orthodox parties in government formation in Israel is also worth noting. Although some governments have been formed without their direct participation, the resulting coalitions have always considered preserving the interests of religious parties crucial for future support.

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center analysis of data covering 199 countries and territories around the world, a vast majority of countries worldwide favour a specific religion, either officially or through preferential treatment. More than 80 countries out of 199 surveyed have an official or unofficial connection to a particular faith.

Islam is the most common government-endorsed religion, with 27 countries - mostly in the Middle East and North Africa - declaring it their state religion. By comparison, 13 countries, including nine European nations, designate Christianity or a specific Christian denomination as their official state religion.

On the other hand, 10 countries - including China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam, and several former Soviet republics - tightly regulate all religious institutions or are actively hostile to religion in general. In these countries, government officials seek to control worship practices, public expressions of religion, and political activity by religious groups.