“I have loved my people with a love that dominated all my sentiments and believed deeply and unreservedly in the fraternity of all peoples.”

—Words inscribed on the tombstone of Emile Touma (1919-1985)

Born in Haifa, Israel, Touma was a Palestinian and Israeli Arab political historian, journalist and theorist. He was one of the most prominent Palestinian Marxist leaders who contributed to the preservation of the Arab identity of the Palestinians in Israel. A distinguished historian and eminent literary critic, he has written many books and hundreds of studies and articles.

In 1937, Touma travelled to Cambridge University to study law, but returned to Palestine after the outbreak of World War II. After the 1948 Nakba—the Palestinian catastrophe that led to the displacement of a majority of the Palestinian Arabs—Touma’s family was forced to take refuge in Lebanon.

In 1949, he decided to return to Haifa, his hometown, which had fallen under Zionist control. His home, too, was taken over by the government. Touma could never enter his home again. Just like millions of Palestinians, who, even today, are longing for the right to return to the hometowns of their grandparents.

For him, home was elusive. However, his wife Haya Touma has kept the memories alive. Born in the town of Orgeyev in Moldova in 1931, she immigrated to Eretz, Israel with her family in 1934. In 1941, the family moved to Haifa. Haya met Emile when she was 18. They married a couple of years later. Haya’s marriage with Emile, an Arab Orthodox Christian, is an example of Jewish-Arab unity.

In this conversation with Sophie Ernst, a visual artist who explores architecture in relation to memory and cultural relativity in works that mix video projection and sculptural installation, Haya, who was also a prominent artist, talks about the childhood home of her husband Emile in Haifa. Unfortunately, Haya passed away in 2009, soon after their meeting.

These are edited excerpts from that conversation where Haya talks about home, memories, belonging, displacement and identity.

The beginning ...

Touma: Always, in your memory and imagination, things are not exactly the same. And so, you begin to build a story. Later on, it becomes a folk story, passed through generations. So, if I tell you the story of my parents, it will be a story that has come back for five generations, talking about mother, grandmother, and so on, until it came to me. I am the fifth generation that was born in the same house that my grandfather lived in, and it will be another story. When I came back (to Moldova), it was a root journey to my people in Moldova. When I came, I saw the house; the one that my great-great-grandfather had built. I came (back from there) and I told my children and it was quite another story. Yes, because we, you see, we are speaking about immigration. We are the Jews who came to Palestine, and then it was Israel. It is a collection of immigrants that came here. In certain times, they came out of ideological or other reasons. If you would ask, let us say, the people who came from the Eastern country, they will tell you another story.

They, or my parents, did not come to Palestine out of any ideological obligation. They came from a very small village, a Jewish village, which was a typical Jewish village. And then in time, it was a changing of history. The Zionist movement began to spread. It was the time of the Russian Revolution. So winds of new ideas came and the young people wanted to look for a new world that was different from the world of their parents who lived in little states. Some of them came to Israel for ideological reasons. The others went to America. They spread all over to find their old ways. Then we had the Holocaust. People lost their roots in many countries and they found other roots to come and build their life in Israel. So, there are many reasons. My parents came here because they wanted to find new ways of life and not to be stuck in this little village or state. My parents brought with them the culture, the Russian culture, the Moldova culture.

They brought with them the food, the songs, the memories of Moldova, of the people and of the history of where they were born. I grew up with the memories that my parents came with. I grew up on the basis of the culture of my parents. It was not Israel, it was not the Jew, it was the Moldova culture. I grew up on the food that my mother brought from the kitchen of my grandmother. You understand? So it was a collection of a lot of people here. Everyone brought with them their own culture, their own food, and it began to build something inside Israel that we did not know how it would develop. We didn’t know how our language will develop, how our culture will develop, how our songs will develop. Everything was new.

When I grew up, I met Emile. It is another story. Emile came from a Palestinian family. They were not immigrants. For centuries, they didn’t know that they had a family tree, that they were Palestinian. They were living here. They had their own culture. They have their own songs, they have their own food, they have their own history; history that belongs to this piece of land.

We were the ones who were the strangers. We had to adapt ourselves to the climate, to the new life. When I say we, I don’t mean the generation that was born here. It is the generation that came from the diaspora here. The generation that was born here, they are already Israelis because they have their own language. The culture began to develop over 60 years. Even the language changed. The way they used to write 60 or 100 years ago changed. It was a new form of the language. It happened out of necessity. Even now, the language is changing with the new generation that is joining the army or they are a part of the kibbutz or are in the other part of Israel. You can’t stop it. It is a process. How will this end? I don’t know how long the change in language will last, or what form it will take. I don’t know.

It is very interesting that when we came to the house, there was an arch. And suddenly, I saw Emile was jumping and he was hitting the arch. “Every time I used to come from school, I used to jump and hit the stone of this arch,” he told me. And then he told me where he was born, about his house and people, but they did not allow us to come. This woman was afraid that we had come to claim our rights to the house. I don’t know. They left in 1948, when Haifa fell.

Two days before Haifa fell, they couldn’t come back because they found themselves as refugees. The house of Emile was situated in Haifa. You have to understand, Haifa has three levels—downtown, the middle town, and the Carmel Mountains. And this is Hadar. So the house of Emile was situated between Hadar and downtown. The fighting was between the Jewish section in Hadar and the Arab section in the downtown. And the bullets fired went through the house.

You can still see the signs of the bullets on the house. So the father of Emile, his brother, they were living in the same house. It was the family house. Every summer, they used to go to Beit Mery, the mountain of Lebanon, to spend the summer there. So they decided to go to Lebanon until everything settled and decided to come back. And because they were living on the second floor, they put a ladder to the balcony. A taxi came to pick them. They couldn’t pass from the other side because it was the Jewish section. My mother-in-law, who was very attached to the carpets, threw them (from the balcony). She threw them and took out the gold. I don’t know how she did that. Later, she brought me some carpets from the old house.

While they were going to Lebanon, the moment they came to Nakura, Haifa fell. They couldn’t come back. They were now refugees, like millions. The house was occupied by the government and a Jewish family came to live there. They did not allow us to come and see the house. It had a balcony, a very big balcony. And they used to tell us that every summer they used to sit on this balcony. They also had horses.

Ernst: And where was the gate that he touched?

Touma: From the other side. This. The gate is still there. The house is still standing. Here, it was here.

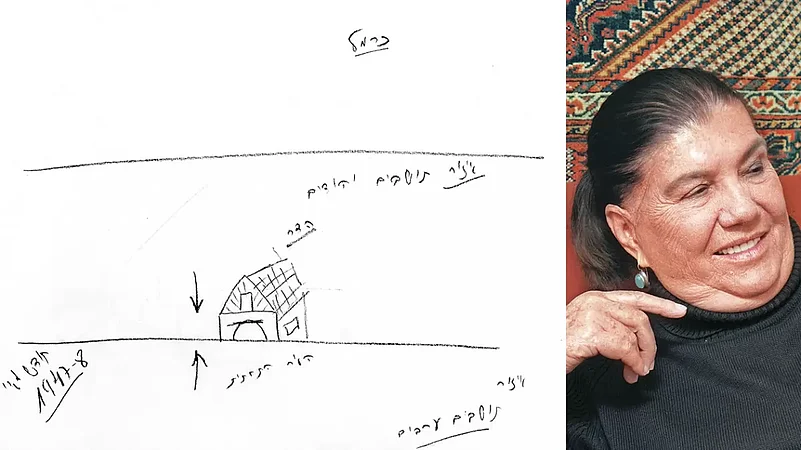

Do you know anything from the inside of the house? Could you draw a floor plan?

(Refer to the image on the first page) Yes. Because it was a Liwan, a very Arabic-style house. This was the gate to the house. This was the main room, which was big. And from this room, you could go to the other rooms. This was the one from here. And here, another room was here. Here was the bathroom and here was the kitchen and here was another room. And then here was the bathroom and here was the kitchen. Here was the kitchen and here was another room. And Emile’s room was here. He was born here. And they told me that the floor was made from white marble, and they had a roof, a wooden roof that was painted. It is still there. And what else they used to tell me? Yes, that the roof was painted with... I don’t know what style of painting it was. They were very rich people. Were they religious Christians? Yes, they were Orthodox, religious people. But the man (Emile) was not. He left home very early. He was studying in Bishop Gobert English School when he was eight or 10.

He was studying in Jerusalem, and then in Cambridge. He came back during the Second World War. And then they established the movement, a national liberation.

I don’t know about this. Can you explain this to me?

This was the first leftist movement in Palestine. They formed, you can say, the first Palestinian Communist Party. But they did not call themselves communist. They called themselves the League to Liberation. They began to organise the workers. They also formed the first Congress for the workers in Palestine. It is like our Histadrut (Israel’s national trade union centre). They were also against British colonialism. They were of the opinion that the Palestine and the Jewish people had to have one government to dismiss the colonialism of the British and to build a mutual Jewish-Palestine government. They said that war will only separate them and it will be centuries of bloodshed. They were against the separation. Then Andrei Gromyko (a Soviet politician and diplomat during the Cold War) and the Soviet Union also supported the separation. Everything is already history. But if you ask me, this was the aim of this group of people.

Then after 1948, the two Communist Parties, the Palestinians and the Israelis, the Jewish, let us say, they are still together. They also have a representation of three in our Parliament.

We met the family many times in Cyprus. It is not only the memory of the house, it is also the memory of and yearning for the country. It is not only bound to the people where you were born. It is all about the complexion of the country, of the people, the place that you are so connected to, the history and the cultural …

And?

It’s about community and family because everybody has left. Some went to America, the young people found their own new way of life. It reminds me a bit of our Jewish history, how people begin to look for other places to begin to build another life. So many people, the young ones, went to America, to Canada. You will find them all over the world. So it was not only the yearning or memory. It is the whole complex, you can say. It is a home. Birthplace is our home. It doesn’t matter if it is in Haifa or ... Understand? This is a connection to the place, to the history of the place. My children, they are living in Germany. They tell me, come and live with us there. I’m not going to live in Germany. I don’t find any connection to Germany. I feel that this is my land, this is my home. I am an artist. I was working in Haga. Every year, we are celebrating these three feasts—Hanukkah, Ramadan, and Christmas or New Year.

And then what I’m doing in my work, already six pieces of work are there in the body. It is on the step of the memory; of individual memory and collective memory. Once I saw in the house a very nice arch; a building that was built at the end of the 19th century. It was blocked. And I said to myself, ‘Who was living in this house?’ Then I noticed a man. He did not leave in 1948 because the original people living here, left in 1948. He stayed there. He went from the house and he collected the photos and also certain documents, and so on. So, when people will return, everybody will like to have the photo of his family.

He actually went from house to house?

Yes. And he collected what he could. He had a huge place there. He died. His son is there. So I talked to Tony, and his father delivered Tony all the stories and everything. I told him, ‘Tony, you know what?’ He told me, give me a few days and I will look through the pictures.

He found a photo of a young couple that was married in the beginning of the century, or next, the last century. I took this photo. I made it bigger, and I built a closed door there. And I put a key. The key is still there on the door. So two weeks ago, and the titles (headlines) were ‘Somebody was living here’, ‘Somebody was living here some time ago’. I had an interview with a journalist. He looked at this and he told me, ‘But it is political work’. I told him, ‘Look here. If a historical fact is politics, it is politics. What is bad about politics?’

Then there is a hand, like when you want to knock, there is a hand. And he said he was joking with me, and added: “But if I knock on the door, nobody will open the door.” I told him, ‘Here is the key, and it is still waiting for the owner to come and open the door. But they did not come. But there is a key. I don’t know how it came to my mind, but it was like this’.

Coming back to my husband and that memory. When we would talk about, let’s say food, he would say, ‘Oh, it reminds me of the food of my mother. And the house. And the feast. It reminded him of all the feasts and how all the uncles and the entire family would gather.

This is the memory about the entire family, about all the friends, about every son, it is ... it all comes together, in circles, the concentration of all—of everything that is the house. It is not just a house that has the windows and the walls. Or the hall. No, it is a whole life. He was 20 or more when he had to leave the house. So the whole the memory of 20 years—that he was born there, it was not only about how the roof looked and how the windows looked. And so, all his life was surrounded and concentrated in these things that you call home.

But there’s this very strange situation. He lived so close to the house because you lived here always.

In Haifa, no? We were in Haifa, yes.

So he lived.

Like he could …

See his house, but he could not go back to it.

He could pass the house twice a day, but he couldn’t reach. He couldn’t get there, because all the properties of people, refugees, it was under the government. You couldn’t get it back. That was the law. And all the houses were in the name of his father. And his father was a refugee.

But what was the law? Because they must have held the deed to the house, no? Didn’t they have an ownership deed to the house?

Like a contract? Like, if I have it, I have it. After the establishment of Israel, the law changed. The refugees did not get anything. Everything is dependent on the government. The government took it upon itself. It is now the property of the government. You couldn’t get it. Millions lost the land, they lost the houses, they lost their life, villages, all villages they destroyed.

You don’t even know the name of the villages in the Palestine time, you don’t know them. Well, the old people, if you wanted to make research work, you have the... But now the new generation, they do not know that above here it was there was a village, an Arab village that was named so and so, because on the ruins of the Arab villages was growing Carmel, let us say. Other cities or other villages, Jewish villages. So all the history, now it is changed. It is a process.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Elusive Home')