“[...] surely, according to any principles, principles they proclaim and the principles I uphold, the last voice in regard to Tibet should be the voice of the people of Tibet and of nobody else.”

— Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India (1947-64)

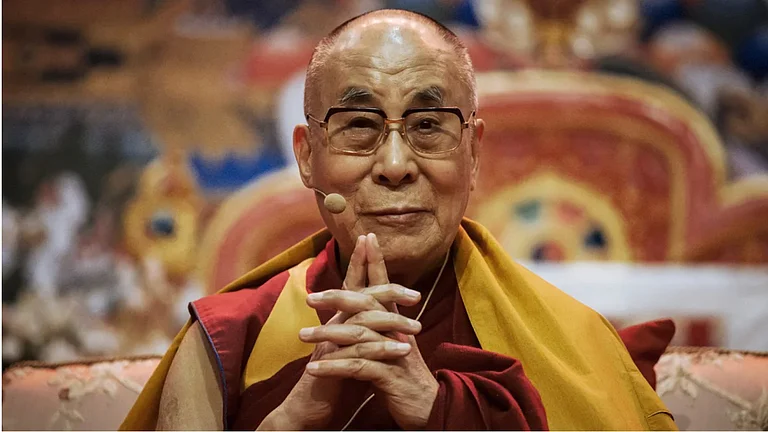

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi wished the Dalai Lama on his birthday in 2021, the Tibet watchers and China hawks saw it as hardening of Indian position on the question of Tibet. For years, New Delhi was quiet in its engagement with the Tibetans in exile in India, but that’s no longer the case.

The shift in New Delhi’s position comes in the midst of ongoing India-China stand-off that has completed three years. The Government of India believes the clashes on the de-facto border, the Line of Actual Control (LAC), drove the India-China relationship to its worst state since 1962 when the two countries fought a brief war that remains an embarrassment for India.

While the Dalai Lama could be compared to the Pope as the leader of a faith, he is much more than that. The Dalai Lama is not a person. It’s an institution. Every Dalai Lama is believed to be the reincarnation of the previous one — the current one is the 14th in line. His birth-name is Lhamo Thondup.

Since 1959, India has been the home of the Dalai Lama. He left the Tibetan seat at Lhasa to arrive in India in exile after Chinese suppression of a Tibetan uprising. Since then, Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh has hosted the Government in Exile of Tibet and over 1 lakh Tibetan refugees live in India, many of whom actively raise their voice for Tibetan nationhood. This remains a major irritant to China and Beijing has termed the Dalai Lama a “separatist” and “terrorist” in the past.

The question of Tibet therefore remains a key component to India-China relationship and the Dalai Lama, as the spiritual leader of the Tibetans, remains central to that component.

What’s the Tibet issue?

The core dispute over Tibet is the nature of the relationship of Tibet and China. While Beijing says Tibet is an integral part of China and has always been such, Tibetans claim that’s not the case.

Scholars say it’s a complex subject as while Lhasa and Beijing had some sort of relationship throughout history —one scholar told this writer it was like that of a princely state and their British overlords during British Raj— there is also evidence of independent or autonomous Tibetan rule. However, no foreign power ever recognised Tibet as an independent state.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Tibet in 1949-50. Following its conquest, the two sides signed a pact called the 17 Point Agreement. The pact promised autonomy; cultural and religious freedoms; continuation of existing political system; and local governance in Tibet. However, Tibetans claim these assurances were soon violated. The pact itself was signed under duress, say Tibetans — a point echoed by New Delhi at the time.

The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) told Beijing in a note in 1950, “Now that the invasion of Tibet has been ordered by Chinese government, peaceful negotiations can hardly be synchronised with it and there naturally will be fear on the part of Tibetans that negotiations will be under duress. In the present context of world events, invasion by Chinese troops of Tibet cannot but be regarded as deplorable and in the considered judgment of the Government of India, not in the interest of China or peace.”

The disgruntlement against the Chinese occupation led to an uprising in 1959 that was crushed by the Chinese. Following the failed uprising, the Dalai Lama along with a large number of his followers escaped to India. For over six decades now, the Dalai Lama and over a hundred thousand of his followers have called India their home. The Dalai Lama calls himself the “son of India”.

While the Dalai Lama talks about the teachings of Nalanda —ancient Buddhist learning centre— and preaches peace and non-violence, no one loses sight of the fact that India hosts one of the biggest irritants of China and allows a government in exile patronised by him to function from its soil.

The Tibet issue, therefore, remains key to India-China relationship, which means that New Delhi’s engagement with the Dalai Lama and Tibetans in exile has also been shaped by the evolving nature of India-China relationship.

The geopolitics of Tibet

As Tibetans in exile and the Dalai Lama remain key irritants to China, the Tibet issue too acquires a geopolitical value. The engagement of India and other countries like the United States with Tibetans is usually seen as part of manoeuvring aimed at China.

The Tibetans in exile, under the leadership of the Dalai Lama, have preached their cause over the decades. In doing so, they highlight the human rights abuses by Beijing and suppression of their culture and heritage. In recent years, such a discourse has found increased resonance as another victim of Beijing’s majoritarianism has found mainstream attention — the Uighur Muslims.

Together, the Uighur and Tibetan diasporas abroad are key challengers to the narrative that Beijing presents to the world. While Beijing presents a vision of a multipolar world where it leads by example of its own economic development, these two communities counter it. Therefore, in supporting Tibetans or Uighurs, the rivals of Beijing seek to score political points as well.

Even as some claim the ‘Tibet Card’ is now overused by New Delhi and has lost its value, the Tibet question remains relevant and unanswered. It is still a central element of the India-China relationship, says Tej Pratap Singh, Professor, Department of Political Science, Banaras Hindu University (BHU).

“India cannot afford to lose Tibet to China. At the same time, it cannot anger China as well. But then one mistake was already made decades back on the question of Tibet,” says Singh, referring to China's invasion of Tibet in 1949-50 to which New Delhi did not respond substantially.

There is evidence that New Delhi expected an invasion to happen at the time. Scholars have also noted that Nehru at the time —incorrectly, some say— did not take proactive action on the issue at the time.

“The invasion itself was not unexpected. A year before, in September 1949, Nehru had predicted that China would invade Tibet, possibly within the year, bringing it to India’s doorstep…Indian policymakers had crystallized their Tibet policy and conveyed it to American officials by January 1950. It basically involved 'leav[ing] the matter alone',” notes Tanvi Madan, Senior Fellow at Brookings Institution, in her book Fateful Triangle: How China Shaped U.S.-India Relations During the Cold War.

Madan further notes in her book, “If Beijing accepted Tibetan autonomy, Delhi would recognize Chinese authority over Tibet. In the meantime, India would continue and possibly expedite its sale of small arms to Tibet and even train Tibetan officers, but it would not welcome the establishment of a Tibetan liaison office in India. Menon also emphasized that India would not take military action if China attacked Tibet. Delhi also resisted Anglo-American pressure to increase aid to Tibet.”

“Such a mistake cannot be afforded again. This means that as China does not respect Indian sensitivities, India too should get harsher on subjects that are sensitive to China, such as Tibet,” says Singh, adding that Chinese actions like renaming places in Arunachal Pradesh should make India adopt a harsher tone in dealing with China.

This leads to the question of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. The Dalai Lama is currently 87. Though he told this writer in 2019 that he would live for another 30-40 years, the fact that his advanced age is a concern of both the Tibetans and New Delhi is not a secret. The succession of Dalai Lama is set to be a contested issue as Beijing has made it clear that it would appoint the Dalai Lama that is bound to be rejected by free Tibetans living outside China-controlled Tibet.

While some say the Tibet Card has been overused, Singh says New Delhi never realised its potential, so the question of it becoming overused does not arise.

“The Tibet card has been used very little and India has always been over-sensitive and accommodative to China. If this card would have been used properly, Sino-Indian border today would have been stable. When we were in position to use this card, we didn’t use it and now with ever-increasing asymmetry between India and China, this card is losing its significance. However, still not everything is lost. India has to show creative and imaginative leadership to use Tibet Card to protect and promote its national interests,” says Singh.

The question of Dalai Lama’s reincarnation

For over six decades now, the Dalai Lama has been the face of the Tibetan movement. While preaching compassion and non-violence, he also presents to the world an alternative side of China, one which suppresses a culture, interferes in religious affairs, and considers an octogenarian a separatist or a terrorist. This way, the Dalai Lama —while being a spiritual leader— has also been a geopolitical actor, though the geopolitical value is now under question with China's increased political and military might. The future of the Dalai Lama is also thus closely linked to geopolitics.

Singh of BHU, however, says that China is not yet at a position where it cannot completely ignore the Tibet issue.

He tells Outlook, “Don’t forget Soviet Union collapsed after more than 70 years of its existence and that too when Soviet Union was a superpower. China is still not a superpower with its limited capacity of power projection in the world. Tibet and Uighur questions are still alive and will remain alive in foreseeable future despite all Chinese repression and use of its deep pockets.”

Beijing has made it clear that it would appoint its own successor to the 14th Dalai Lama. The Tibetans in exile have rejected the idea and are bound to reject Beijing-anointed successor. That would be a major point of contention.

“The Dalai Lama appointed by China would pursue Chinese interests, whereas the one appointed by the Tibetans in exile would pursue an independent line. This would have national security implications as well,” says Singh.

If the Chinese-anointed Dalai Lama acquires acceptance, it would mean he would peddle Beijing's vision and would mark an end of the geopolitical role the 14th Dalai Lama has played for over six decades.

However, the Dalai Lama has made it clear that the future of the institution rests with him and the Tibetans. He has also said that the teachings of Buddhism are important, not the institution of the Dalai Lama.

The Dalai Lama told this writer in 2019, “Some Chinese hardliners express views about the 15th Dalai Lama. They have to wait at least another 30-40 years. The reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, the future of the Dalai Lama, is ultimately in my own hands. At the time of my death, I will write some will. So my rebirth, I think, will be somewhere in the Buddhist community. As early as 1969, I made clear even [that whether] the institution of the Dalai Lama should continue or not is up to Tibetan people. Reincarnation is not important. It’s important that Buddha’s teachings remain.”

Speaking to this writer and his fellow student-journalists at his residence in Dharamsala in 2019, the Dalai Lama further said he has written books and his teachings have been recorded, which would remain even after his death.

Even though the Dalai Lama downplays the question of succession at times, often with his characteristic laughter, the question acquires greater prominence by the day. In his book The Himalayan Face-Off: Chinese Assertion and the Indian Riposte, Shishir Gupta notes that the question is not just about the Tibetan spiritual leadership but about the broader movement as well.

“There is a strong need for a Tibetan leader to be in place during the current Dalai Lama’s lifetime with the credibility and political weight to lead Tibetan politics…A PRC-anointed Dalai Lama will clash with the Gelugpa sect head appointed outside of Tibet and sow the seeds of confusion among the Tibetan struggle,” notes Gupta.

Gupta further notes that, in the absence of the Dalai Lama, the extreme elements among Tibetans could turn the movement militant which would be a concern for India, which means that interests of India lie in a smooth succession.

He notes, “Naturally, it is in the interests of New Delhi that Tibetan refugees in India conduct a peaceful political struggle as any radicalisation or its subversion would have an irreversible impact on bilateral ties.

“In the absence of a widely accepted Dalai Lama, the pro-freedom struggle, which is already showing signs of frustration with its acts of self-immolation, could degenerate into a proper guerrilla struggle with sporadic acts of terrorism in the [Tibetan] plateau…Just as New Delhi felt that Tibet could go into a free fall after the demise of the 14th Dalai Lama, the Xi Jinping regime made preliminary overtures to Dharamshala in July 2013 in recognition of this concern.”