If the term ‘translation’—which is absent in all Indian languages in its etymological Western sense—is taken to represent anuvad, tarjuma, bhashantar, rupantar, teeka, vivartnam, etc., for convenience, one can easily claim that India boasted a dynamic, self-renewing and evolutionary tradition of translation until the onset of the 20th century, when, under the influence of the colonial discourse and romantic notions of faithfulness, equivalence and Frostian anxieties of what is lost in translation struck roots. Simple questions of who can best translate poetry, what is the ideal level of linguistic proficiency to undertake translation, which language to translate from and into, and so on, began to dominate the discourse around literary translation, as if to suggest that translation took place between languages and cultures poised on equal footing, and that the exercise was devoid of power politics. I too lapped up this theory and early in my career, ferociously translated mainstream Gujarati literature, partly out of naivete, partly out of a lust for climbing the academic ladder. Among other things, my translations confirmed my male, majoritarian upper class-caste worldview and shored up a proud identity of an inheritor of a rich cultural heritage. But in 2002, time froze and the ontological shift in the life of this translator occurred.

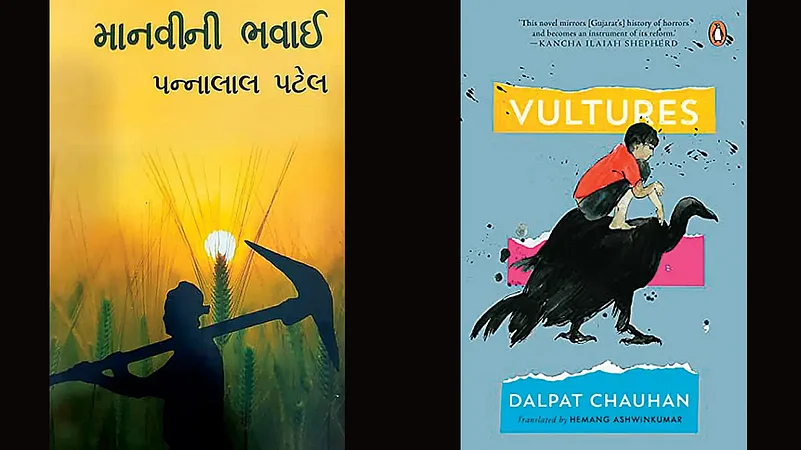

The horrors of Godhra and the massacre that followed made me rethink the role of translation in a society fractured not only on religious but also on linguistic lines. Shaken and sickened by the literary response to the spate of violence, I set out on the project of translating Arun Kolatkar’s long poem Sarpa Satra (2004) into Gujarati. Though I have elsewhere written at length on the politics of that translation, the rendering was in an alternative theoretical space altogether—a space of mourning. One thing became clear to me. Translation wasn’t a value-neutral exercise, taking place in an ideological vacuum. A translator, located at the intersection of multiple discourses within a contested multilingual, postcolonial terrain, turned out to be a vector of power and s/he had to decide which way it flowed, towards the powerful or the powerless, towards the oppressed or the oppressor. Disillusioned and deeply suspicious of the literary representations of the state, its people and its past, I embarked upon a reading spree of Gujarat’s literary and cultural histories, from above as well as from below, hoping to stumble upon alternatives and subversions. And stumble upon I did, when I ran into Dalit writer Dalpat Chauhan’s short story The Payback, which challenged the zeitgeist of the 20th-century Gujarat, the invincibility of its spirit and its proud agrarian identity. The story is a subversive take on eminent Gujarati writer Pannalal Patel’s novel Manavi ni Bhavai (Endurance: A Droll Saga), which, published on the eve of India’s Independence, fetched the author the prestigious Jnanpith Award in 1985. The defining theme of the novel, from which probably the English translation derives its title, is the crushing agrarian angst articulated by the protagonist Kalu, when he queues up for charity grains during the Great Indian Famine of 1899-1900. He says, “It’s not the hunger really, but the act of begging to douse it, which demeans.” In his story, Chauhan develops the theme within a caste framework, and brilliantly shows how during the famine, the pauperised, famished, upper-caste villagers shed their caste inhibitions and showed up under the cover of night at the door of untouchables to beg for sun-dried meat from carcasses. While Chauhan’s story subverted the collective memory, pointed out gaps in the popular narrative, and made silences therein, it also recovered an alternative memory—the vulture’s memory—which had been shunted to the margins for its starkness. Reading through the huge corpus of his literary output, through a vulture’s hermeneutic of lived realities—shot through with daily humiliations and unspeakably brutal caste violence—the translator in me broke out of his cultural cocoon. I realised the staggering magnitude of blood curdling atrocities, colossal injustice and gut-wrenching dehumanisation heaped by my ancestors on a community for thousands of years. It looked genocidal in proportion. Once again, I decided to step into the space of mourning to translate Chauhan’s works. But now, the stakes were high, almost Himalayan.

How to handle the issues of aesthetics, experience and epistemology? Reared within the conceptual triad of Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram, and accustomed to the aesthetics of dhwani and ouchitya, I was unnerved by the prospect of capturing the quintessential Dalit experience—the materiality of untouchability and consequent naming of the Dalit as the unclean, impure Other—“through a minute chronicling of the smallest detail of daily life in a language that is crude, impure and uncivil” (Limbale, 2004: 12). The roots of the non-canonical and counter-hegemonic aesthetics of Dalit literature lay in a unique epistemological foundation of Dalit consciousness, historically formed through an intimate, day-to-day interaction with prakriti, as well as through the experience of colonisation and exploitation. Concomitantly, a recurrent theme of Dalit epistemology related to a radical anti-caste ethos; a ceaseless questioning of caste irrationalities, exploitation of labour and negation of Dalit humanity. You could certainly imagine what all this would have meant to an urban, upper caste man who was trained into believing that caste was a thing of past. That apart, my biggest challenge lay in accessing and comprehending what political scientist Gopal Guru calls the “everyday social” unfolding in a Dalit text—the ensemble of the smell, sound, taste and touch that are peculiar to the Dalit social life, and the distinctive and differential associations they carry for dialectical socialities. If the issue: “Can a Savarna translate Dalit literature?” was not daunting enough, the question of who ‘may’ translate it, stared hard at my face. My hand began to shake at the shady dynamics of the cultural economy of English translations of Dalit texts—exposed by poet and publisher Yogesh Maitreya—where everything except the source text was Savarna. These were all valid issues to be considered while attempting to construct a social imaginary.

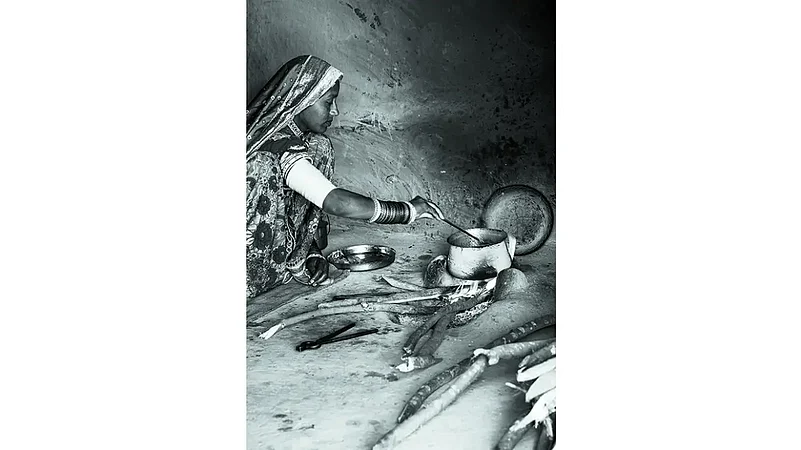

What to do? Despairing and restless, I began squirming as I sought a way to imagine a collective future that could avoid reducing social life to essentialised identities of different kinds. The pandemic helped by extending the “tortuous semantics of tactility” (V. Geetha, 2009: 97) across the hierarchical caste order, and directed the fear of death hidden in the act of “touch and recoil” (V. Geetha) from the body of the Other to the Self. It afforded me the experience of untouchability, though vicariously. For epistemological shift, I decided to scour the 1,000-year-old socio-cultural history of Dalits in Gujarat, which took me to the story of Veer Mayo, a Dalit cultural icon who bravely sacrificed his life to secure dignity and humanity for his community in the 12th century. The ghastly 19th-century practice of sacrificing Dalit children in times of epidemics to appease the goddess of epidemic, the untiring struggles of Dalits to enter schools, buses, hotels and temples, the injustices meted out during land reforms, and the gory details of anti-reservation riots of the 1980s, turned out to be a few high(lighted) points in the saga of suffering the community had underwent. Reading Dalit literature exposed me to a disturbing history that was missing from mainstream sociological and historical accounts. After such comprehensive debriefing, it began to seem possible for me to break through the Gujarati Dalit social, through an act of secondary witnessing—the act of attentive, empathetic and conscientious listening/reading. The final challenge was to comprehend the alternative discursiveness and poetics of Chauhan’s work, and map it, just as poignantly, on to the translation. A tough task, almost anthropological in its endeavour. Long discussions with Chauhan over the phone followed—threadbare discussions over the form, feel and symbolic features of the objects in his texts, the terms of social contract Dalits had with the village proper, specifics and rationale for Dalit rituals—not just religious, but also social—like the method of skinning a carcass, processing a hide, medicinal system, and so on. While this gave me an entry into a new experiential universe, I suddenly realised that without knowing it, I had begun to learn and use the Dalit dialect of north Gujarat in my everyday life. Emboldened, and much to the chagrin of my mainstream poet-friends, I rendered Arun Kolatkar’s poems Pi-dog, Song of Rubbish and Boomtown Lepers’ Band into

the Dalit dialect, in my book-length Gujarati translation of Kala Ghoda Poems, to underscore the direct correspondence between a dog, some rubbish and an untouchable, in Hindu orthodoxy.

In a decade, I was ready with English translations of Chauhan’s select stories and his novel Vultures. The difficulties I faced with magazine editors and publishers ranged from sublime to silly: the defamiliarising style of translation, the far-fetched idiom, the scatology, the unreality of the account to the plain, commercial “short stories don’t sell” spiel. Dwelling upon them would require a tome. But, after all these years, what has stayed with me—something which pegs me down with enormous pain and despair—is the stunning scale of violence Dalits have been subjected to. Its unimaginable brutality and inhumanity sobers me down. While I was translating the climactic episode in Vultures—in which Chauhan gives a searing description of Iso’s murdered body—a wooden peg used to tether a horse in a shed is hammered into his backside—out of deep anguish, I pressed my fingertip on the head of a needle, and realised what it means to be human. To translate is to be human, and a lifetime is not enough to realise the humanity of people, oppressed on account of their caste, religion, gender, sexuality, language and ethnicity.

(Views expressed are personal)

Hemang Ashwinkumar is a bilingual poet, translator, editor & critic