As the Chinese Communist Party amends its constitution for Xi Jinping’s emergence as its most powerful leader since Mao Zedong—forcing the outside world to take note of this extremely significant development—the leadership in New Delhi too, keeping the new ground reality in mind, has begun to make necessary adjustments in resetting its relations with the Middle Kingdom.

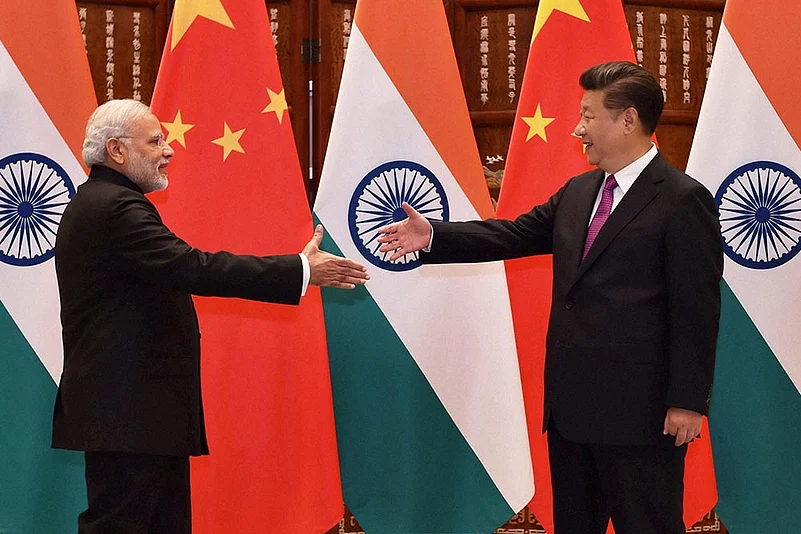

A serious attempt is being made by the Narendra Modi government to move away from the strains that plagued Sino-Indian ties for the better part of last year, culminating in the Doklam crisis—the longest military stand-off between the two neighbours since the Samdorong Chu crisis in 1987—to move to a more cordial engagement with China.

Indian defence minister Nirmala Sitharaman is likely to visit China later this month—a visit at this level from New Delhi after two years—to hold talks with senior members of the Chinese government and military for reviving the Confidence Building Measures agreed between the two sides to ensure a calm and stable border.

In coming months, a number of other visits are also being planned between officials and leaders of the two countries to strengthen bilateral engagement. All this is being done to create the right atmosphere for a meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi in Qingdao, China, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summit in June.

Former MEA secretary K. C. Singh says, “Modi’s foreign policy is mainly tactical. So we will have to see how it pans out.” But Oxford historian Rana Mitter, a specialist on republican China, feels, “The rapprochement should be encouraged. India and China are second-order problems for each other,” he says, pointing out that Pakistan is more important for India, while Japan and the US are for China. “Neither of the two countries would benefit from confrontation,” he adds.

A recent memo written by foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale to cabinet secretary P.K. Sinha reflects this shift in South Block’s approach towards Beijing. Advising caution on the Tibet issue, Gokhale has requested the cabinet secretary to ask government functionaries to stay away from a series of public functions planned in the capital to celebrate 60 years of the Dalai Lama’s exile in India. The note was clear that at “this very sensitive time” in Sino-Indian relations, it was best to avoid issues that can unnecessarily anger China.

The Tibetan government-in-exile has now cancelled two major events in Delhi—an inter-faith prayer meeting at Rajghat on March 31 and a ‘Thank You India’ event at the Thyagaraj Sports Complex on April 1.

Predictably, Gokhale’s pragmatic approach did not go down well with all sections. The fact that the sensitive memo to the cabinet secretary was leaked to the press clearly shows the level of disquiet among some government officials. The disappointment is acute among diehard Modi supporters and the hawks in New Delhi’s foreign policy establishment. Most of them believed that it was a mix of resolve and tough-minded diplomacy on India’s part that resolved the Doklam crisis and hence, infer that the best way to deal with our assertive neighbour was only through a tough response.

Some moderates in the establishment accept the need for a more cautious approach vis-a-vis China, but question whether India had to bend backwards to appease Beijing’s sensitivity, as was done in getting the Tibetans to call off the Rajghat prayer meeting.

As things stand, if at all there are any celebratory functions at the Dalai Lama’s headquarters in Dharamshala, they will be at a much lower key than what was planned.

Interestingly, the efficacy of ‘Tibet’ as a bargaining tool to deal with China has never quite been explicated by Indian policy planners. Yet, some of them continue to entertain hope that—being the host of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile—the ‘Tibet card’, if used effectively, can put Beijing on the back foot.

However, former foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal admits, “Though the Tibet card has been played from time to time, it is not very clear what we have got in return.” Similar views are expressed by senior fellow at Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research, Srinath Raghavan. “If we can’t even poke the Chinese in the eye, what is the point of playing a card that only exposes India’s hostile intentions and antagonise China?” he wonders.

Of course, China’s extreme, and relentless, sensitivity to the ‘Tibet’ issue ever since its takeover in 1950 is all too well known. And it has always been hyper-suspicious of any Indian ‘design to foment trouble’ there. In fact, Chinese apprehensions about India’s role in Tibet, along with the disputed boundary, were the key factors behind the Sino-Indian War in 1962.

Though with large-scale development, communication and resettlement programmes China has consummate—and globally unchallenged—control over Tibet, the leadership in Beijing bristle with rage at the slightest criticism of its Tibet policy. The Dalai Lama, a revered, spiritual figure in India, is seen more as a political leader and is called a ‘splitist’ by Beijing. Much of the tension that crept into Sino-Indian relations last year happened in the wake of India’s decision of allowing the Dalai Lama to attend a religious function in Arunachal Pradesh.

For all that, the recent move to re-engage with China emerged out of a mutual recognition for cooperation. Indian officials point out that the desire to make a fresh beginning came from the Chinese side, when two of its senior leaders—state councilor Yang Jeichi and foreign minister Wang Yi visited New Delhi last year and felt the strains of Doklam should be kept aside in favour of better ties. When foreign secretary Gokhale visited Beijing last month, New Delhi made clear its intention to match the Chinese gesture and put bilateral relations back on track.

However, the question remains in Delhi and elsewhere about how China, now under Xi’s elevated status, will behave.

“China could turn either way,” says Mitter, pointing out that economically, its expansion could be genuinely valuable to the wider world, with its commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement. But he also cautions about a probable scenario where China’s military strength drives it to restrict access to the Asia Pacific region or into a confrontation with neighbours. “It’s not all about China—the rest of the world needs to be assertive but positive about its goals,” he adds.

Modi certainly has taken a risk by backing his foreign policy team in this new initiative on China. But, for the current move to work smoothly, a lot will also depend on developments in the neighbourhood.

“A primary requirement is to urgently move away from this zero-sum rivalry where every move by India or China is seen as inimical to the other,” says Raghavan.

The attempt of the two sides is to revive the spirit of the 2015 Joint Statement that spoke of “respect and sensitivity to each other’s concerns, interests and aspirations”.

How much of this can be translated in real terms will be known after the meeting between Modi and Xi in June. The path they want their countries to tread in the coming days will be crucial for the future of Sino-Indian relations.