Despite recognising the pre-eminence of the US on the world stage, Indian leaders have traditionally been wary of getting too close to America. Successive governments have tried to forge strong bonds with Washington—a desire that became more evident in the post-Cold War period—but without compromising on their pursuit of an independent foreign policy, maintaining equally strong bonds with other major powers. But as Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares for next week’s visit to the US (June 7-8), his fourth in two years and second to Washington this year, the unprecedented bonhomie in Indo-US relations has begun to both encourage and bother many people, within and outside the country. What’s driving this closeness? What are its implications for India, the region and beyond?

For obvious reasons, Modi’s supporters and sections within the Indian establishment are charged up, hoping that with America’s active support, New Delhi will find a legitimate place on the world stage. But sceptics worry, considering the US’s long history of fickleness and of its proneness to entertain but not quite honour another country as an equal partner. So is India junking its foreign policy, derisively called “Nehruvian non-alignment”? Is India favouring a close partnership with the US to do its bidding in Asia—to become, in effect, the ‘Voice of America’? A proposed US Congress legislation to make India a NATO-like ally, bracketing it with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel and South Korea, considered by US critics as American stooges, is also deepening concerns about Delhi’s future and ‘sovereignity’. Or is India using its growing closeness with the US to create more strategic space for itself to push development and face regional and global challenges?

As most observers search for proper answers to explain these fast-paced developments, some point to an obvious third force—it’s the rise of an assertive China, they say, that is the driving force bringing India and the US in a tighter strategic embrace than ever before. “Of course China’s rise is one important factor underlying the new India-US partnership,” says John Garver, author and professor emeritus at Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta. “China’s military power has grown very rapidly. Virtually all the countries around China—and the US too—are apprehensive about how China will use its growing power. There are troubling signs in the South China and East China Seas.”

The US’s power and influence, in relative decline since the global economic crisis of 2008, is being seriously challenged by China, already the world’s second largest economy. And Asia, a region with most of the fast-growing economies, is being seen as a main area that could push the global recovery. For India, widely speculated to become the world’s third largest economy in 15 years, China is both an opportunity and a challenge. It needs Chinese investment for infrastructure development and makes common cause with Beijing on issues ranging from international finance and trade, to climate change and environment. But India also faces serious challenges from it on the disputed and unsettled boundary and other security-related issues, including Beijing’s growing military-political-economic cooperation with Islamabad. Joining up with America and its allies, especially those with a maritime boundary dispute with China, New Delhi feels, will give it the leverage, including in the taking of meaningful steps on boundary clarification and forcing Pakistan to stop terror activities against India. Says Garver, “Modi may be attempting to use China’s fear of Indian participation in a US-Japan-Australia-Vietnam coalition to persuade it to be more responsive to India’s security concerns.”

Many share this view. C. Raja Mohan, a leading columnist on international affairs, wrote in an article on the eve of President Pranab Mukherjee’s recent visit to Beijing that the president should convey to the Chinese in no uncertain terms India’s displeasure at China’s decision to block Delhi’s membership of the elite Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), adding that: “Whether we have leverage or not, we have to communicate directly to the Chinese on the importance we attach to the issue.”

President Xi Jinping and Modi in Delhi

Other observers sense different reasons behind the growing Indo-US ties. Some interpret Modi’s enthusiasm for America as a reflection of an “aspirational” leader’s attempt to be recognised by the world’s most powerful nation. Others point to India’s growing stature as a player on the world stage, its increasing economic clout, its military muscle and attractive market, and above all its attraction as a stable, peaceful democracy. “We always had cordial relations with India. But now we are becoming close, strategic partners,” says Nicholas Burns, former US undersecretary for political affairs in the state department and Harvard University professor.

Indian officials say Modi’s two days in Washington will be spent in wide-ranging discussions with President Barack Obama and senior members of his administration. But if one wonders how much is expected from a ‘lameduck’ president, one must remember Modi is also spending a lot of time on Capitol Hill. He’s being honoured with a joint address to the US Congress, something reserved only for leaders considered important. His scheduled engagements with important US politicians, including key members of the House of Representatives and the Senate, is also a clear indication of the keenness in the US for India as an ally. “The idea is to reinforce India’s image as a key partner to the US Congress,” says Srinath Raghavan of Delhi’s Centre for Policy Research. “The Congress, after all, has an important role to play. Doing this in a presidential election year will also help ensure continuity when the next government comes in.”

To put things in perspective, India has been searching for ways to tie up with the US since the Cold War ended. A drift towards America had begun soon after Pokhran-II in May 1998. Key members of previous governments in Delhi too were desirous of a strong Indo-US relationship. This finally led to the Indo-US civil nuclear deal a decade later, when the George W. Bush regime threw open the doors of the elite club to recognise India as a legitimate nuclear power. Meanwhile, Indian leaders had been building relationships with powers in the neighbourhood, including rivals like Pakistan and China.

But since Modi became prime minister, the equation seems to have undergone a significant change. His frequent trips to the US seem more surprising if one remembers that not too long ago, he was persona non grata for the US for his role in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Indeed, the US had denied him visa despite his being a chief minister. The 2014 parliamentary elections changed all that.

The massive mandate with which he came to power—a feat unmatched by other parties in 30 years—was something not lost on the Americans. His business-friendly image fuels hope in the American mind that reforms in the insurance and banking sectors, which could mean business opportunity for American corporates, seem more than a possibility. But while all these factors are important to make India an attractive partner for the US, most observers also recognise that in this growing partnership, the China factor is looming large, giving a geopolitical edge to a strong Indo-US partnership.

MEA officials point out that Modi’s visit to the US is part of his five-nation tour, which will also take him later to Afghanistan, Switzerland, Qatar and Mexico. But there is no doubt it is his visit to Washington that is being watched in other world capitals. It may therefore come as no surprise if developments in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly that in South China Sea, and possible maritime cooperation between the two sides and better coordination between their navies, figure prominently during discussions between the two sides.

“China is a balancing act,” says Burns, pointing out that both India and the US need its cooperation on a number of issues, ranging from the economy to climate change and in dealing with many other global challenges. “But at the same time, China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea is making its neighbours nervous. It is running roughshod over countries in the region.” It is here that America sees a role for India, a country that is not only “peaceful and stable” but one that is becoming a “very important player, economically and otherwise, in the world”.

However, the important question is, how will India respond to this American offer? “China is but one of the things that India is, or rather should be, concerned about,” points out Raghavan. But he feels that, while India is keeping a weather eye on South China Sea, there is no reason for New Delhi to be too concerned. “We are echoing the US line on the threat to ‘freedom of navigation’—a euphemism for the American navy being able to patrol close to China’s coastline. However, given China’s own overwhelming dependence on these sea lanes for its imports and exports, I don’t see why they would want to threaten navigation in the South China Sea,” he says. “The Chinese aren’t exactly given to cutting their nose to spite their face.”

But since coming to power, the Modi government has been reaching out to many countries on the periphery of China, especially in East and Southeast Asia, to forge closer and deeper bonds. Much of this is being done with the argument that if China can develop strong ties in South Asia, nothing should stop Delhi from doing the same in the domain closer to China. Modi chose Japan as the country for his first bilateral visit after becoming prime minister. Not only that, he also issued a joint statement with the Japanese criticising “expansionist” tendencies of countries, without naming China, but with the reference obvious. Subsequently, he also joined Obama to issue another statement committing India to work with the US to maintain peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean region—another clear signal.

Modi with Nawaz Sharif at a SAARC meet

So how do other countries in the region look at these developments, particularly the leadership in Tokyo, which too, has a very complex relation with China? “Japan has long had a great common interest with both the US and India, but particularly today, as China asserts itself in the maritime Indo-Pacific,” says Sheila Smith of the US-based Council for Foreign Relations. “Tokyo’s strategic planners hope to continue to deepen their ties with New Delhi.”

Smith points out that the Malabar exercise last year that Japan took jointly with India and the US took it a step closer to realising a full strategic partnership with these countries. She says there is room to improve economic ties and Japanese businesses would be eager partners with Indian firms in going forward in this area. She feels that “anchoring strategic cooperation to deepen and broaden economic ties would be yet another way to diversify the growing discomfort many in Japan and India have with China’s growing economic leverage.”

“Russia appreciates the geopolitical situation of India and its security requirements,” says Dmitri Trenin, head of Moscow’s Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “There is general trust, however, in India’s determination to be its own master. As long as that holds, the Russo-Indian relationship will remain largely intact.”

But while all this is being done to deal with an “assertive” China, a move seen in Beijing as an attempt to contain its rise, how will the Chinese leadership react? “The Chinese have already taken note of the series of things India has done to sidle up to the US on this issue,” says Raghavan. He points out a range of issues—from Pakistan-sponsored terrorism to the blocking India’s entry in the NSG or trying to increase India’s discomfort in the neighbouring countries, like Nepal—as clear indications that they won’t accommodate India’s interests if India goes blatantly against theirs. “A government which assumes that consequences don’t matter in making choices is clearly out on a vacation,” he says.

However, as indications suggest, despite its growing disappointment, China too needs India. As long New Delhi’s growing ties with Washington remain within the space for strategic gain, without getting into a military alliance with the US, the Chinese leadership perhaps will be able to live with the developments.

As Garver argues, for Modi’s triangular diplomacy to work, he needs to convince Beijing that there is a real danger of India abandoning its “strategic autonomy” without actually doing so. “Overplaying the US card would diminish, not strengthen, India’s security vis-a-vis China,” he says. One can only hope Modi and his enthusiastic advisors are listening to these cautionary remarks. Maybe the growing Indo-US ties will only help expanding India’s strategic space and not end its sovereignity.

***

Warming India-US Ties

- Modi has been the first Indian PM to visit the US thrice and hold as many bilateral meetings with an American president

- India’s defence cooperation with the US has increased significantly under the Modi government

- Ending its past reluctance, India signed the Logistics Assistance Agreement with the US that will bring the two navies closer

- India has increased its engagements with Japan and other US allies in Asia, seen largely as a move against China

- The US Congress is seriously considering a move to give India the status of a NATO-like ally to indicate their growing closeness

The Downside Of The Closeness

- US has not yet come out in support of India’s position in its boundary dispute with China—there is no guarantee it will do so in future

- The Sino-Indian boundary has been quiet for years unlike the one with Pakistan. Renewed tension can also make it active.

- India’s decision to host Chinese dissidents could lead Beijing to host and encourage similar anti-Indian forces within China

- The America-initiated G-2 arrangement with China is still on the table. If it is revived, India may find itself relegated to the sidelines.

- India’s growing closeness with the US, if turned into a military alliance, will also alienate traditional ally Russia

***

China’s growing closeness to Pakistan troubles India

India’s Grouse Against China

- Despite support of other countries, China has so far refused to back India’s entry in UN Security Council as its permanent member

- Raising “technical” points, China has blocked several Indian attempts at the UN to proscribe Jaish-e-Mohammed and Pakistani terrorist Masood Azhar

- China has also blocked India’s entry in the Nuclear Suppliers Group and demanded Pakistan should also be made a member

- China has made heavy investment in building highways and other infrastructures in PoK, though India and Pakistan are yet to resolve the Kashmir dispute

- China, which helped Pakistan develop its nuclear and missile programmes, continues to have a robust military cooperation with it

***

Shinzo Abe in Delhi

India’s Provocation Against China

- Modi openly criticised China for its “expansionist” tendencies in Japan while on a maiden bilateral visit there as India’s PM

- Unlike his predecessors, Modi is more vocal in demanding freedom of navigation in the Asia-Pacific region with an eye to pressurise China

- The Modi government has been more active and vocal in supporting Japan, Vietnam, Philippines in their maritime dispute against China

- Modi issued a joint statement with Obama to join US efforts to promote peace, security and stability in the Asia-Pacific region

- His government also allowed Chinese dissidents to meet in Dharamshala and demand political reforms in China

***

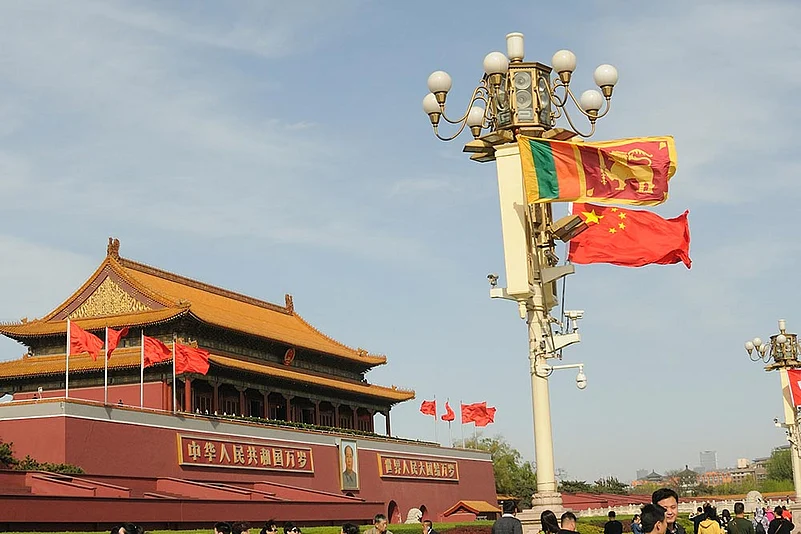

Chinese and Lankan flags on a pole in Tiananmen Square

China’s Growing Footprint In Asia

- China is Sri Lanka’s biggest investor and has been active in developing its infrastructure, including the Hambantota port and the mega Colombo port city project

- Chinese investment in Maldives tourism, infrastructure and maritime security has been on the rise in the past years

- Nepal entered into a trade and transit agreement with China, quite obviously to find an alternative to the Indian route

- Chinese presence in Bangladesh has been growing both in trade, infrastructure and also defence cooperation

- China is Pakistan’s closest and ‘time-tested’ ally and their all-round cooperation continues to grow further as Indo-Pak ties get strained

- China’s wide range of investments and involvement in Myanmar gives it an edge over others; tense Sino-Indian ties can lead China to encourage Northeast insurgents to create trouble