Nawaz Sharif could well have written his name, in indelible ink, in the history of Pakistan. Another 10 months through the crucial, last stretch of his tenure and he would have gone down as Pakistan’s first prime minister to have survived in office for a full five years.

In seven decades, Pakistan has not had a single premier to have lasted a full term. Despite its claim to be a democracy for over three decades, the country has largely been run by the army’s writ. The army looms over all other institutions; survival of elected politicians have mostly depended on the pleasure of the generals.

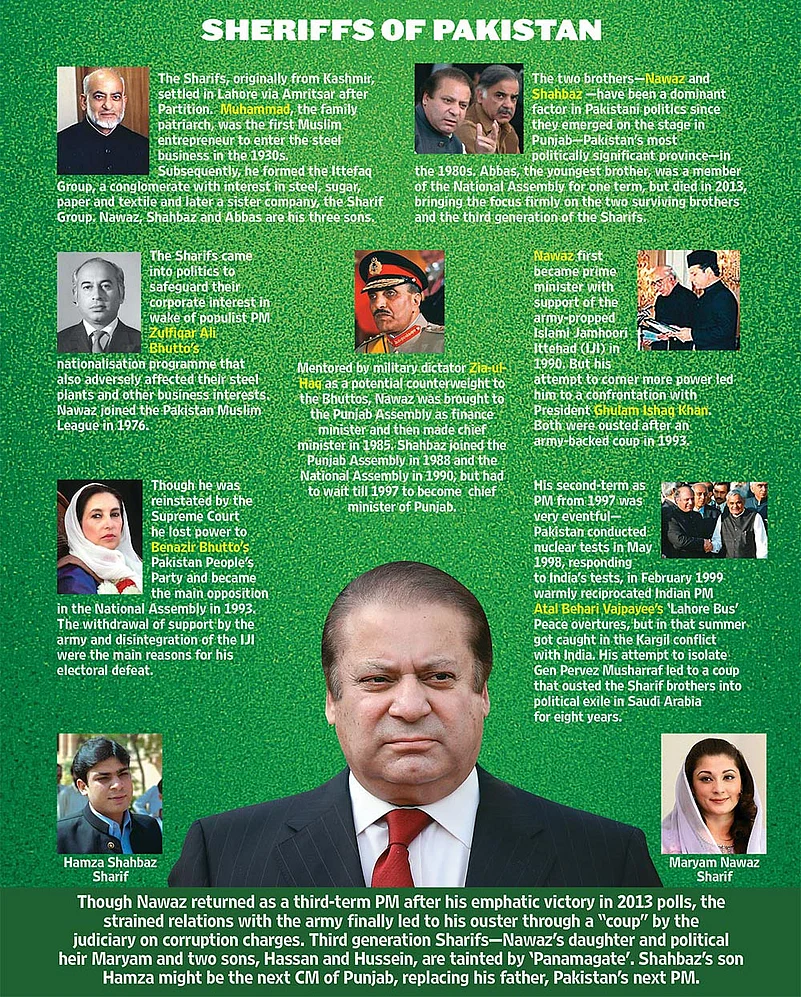

This time around, however, it was Pakistan’s apex court that dealt the blow to the elected prime minister, forcing his ouster. The Panamagate corruption charges against Nawaz and his children, including his daughter an heir-apparent, Maryam, claimed its prey as Sharif was disqualified by a five-member bench of the Supreme Court, forcing him to resign from Parliament and raising concerns that this would again lead to one of Pakistan’s cyclical phases of political uncertainty.

The country is unlikely to descend into “violence and chaos”, says former Indian diplomat M.K.Bhadrakumar. “There is great turbulence, but that is going to play out in the corridors of power and as party politics,” he writes on an Indian website. But opinion among experts is still divided on the fairness of the judgment—many see it as a coup by the judiciary on the instigation of the army.

“Notwithstanding the scepticism over the judgment perceived as radical, the action came from within the system and not outside the constitutional framework,” opines Dawn columnist Zahid Hussain. It also signifies a milestone in the development of a judiciary independent from, and unafraid of, the executive, he argues, admitting, “Though the perceived harshness of the ruling can rightly be disputed.”

What turns and contortions Pakistani politics will take between now and June 2018, when the current term of the National Assembly ends and fresh elections to parliament are due, is a moot question. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, a former petroleum minister and close aide of the ousted PM, has now stepped in his place. It is believed that he is keeping the seat warm till Nawaz’s younger brother and the current Punjab chief minister, Shahbaz Sharif, gets elected to the National Assembly and takes over. Shahbaz’s son, Hamza, is likely to replace his father as Punjab chief minister.

This, of course, is a well-crafted strategy of the Sharif family—a significant force in Pakistani politics since the 1980s—to preserve their immense influence and power. Perhaps a more relevant question is whether the army will allow the Sharifs to play that role.

“Much depends on the ability of the successor government led by Sharif’s brother Shahbaz Sharif to hold on to power till the government’s term ends in June next year,” observes Bhadrakumar. According to him, if it can survive till then, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) would have a fighting chance of even winning the polls, or at least emerging as the single biggest party. “Again, do not write off Nawaz Sharif. An unfair thing has been done to him, and Nawaz is a fighter with a record of rising from the ashes like a Phoenix,” he adds.

A major factor in the family’s continuing political relevance would be the comfort level of the army top brass in having another Sharif at the helm. “Shahbaz Sharif is a level-headed politician and a competent administrator. He knows how to forge a working relationship with the army leadership,” says Bhadrakumar. The danger, he opines, lies in the PML-N unravelling. A weakening PML-N serves many interest groups. “However, on balance, the party will stick together, since it is in power in both Islamabad and Lahore,” adds Bhadrakumar.

For many within the PML-N, the main worry comes from the party’s main base in Punjab once Shahbaz takes off for Islamabad as PM, leaving the crucial province either to his son or someone else. Many PML stalwarts feel Shahbaz should not leave Lahore, Nawaz should allow Abbasi to continue as PM and, if need be, guide him from behind the scenes.

It is, however, interesting to note how relations between the Sharifs, essentially propped up and brought to the political limelight by the army to counter the influence of Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), turned sour.

The Sharifs, essentially a business family that was a pioneer in the country’s steel business, came into politics not because of an idealistic need to serve the people, but to safeguard their wealth. It was a reaction to the move by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to nationalise key industries like the steel plants that forced the Sharifs to join politics. Nawaz, the eldest among the Sharif brothers, was initially helped by the army in Punjab to become the chief minister and later at the national level, when he was made PM in 1990 for the first time. But relations were on a rocky path. Nawaz’s attempt to expand his influence and power brought him in confrontation with Pakistan’s then president, Ghulam Ishaq Khan. Later, both were forced out of power by the military rulers.

Nawaz returned for the second time in 1997 with a much stronger mandate and initially enjoyed the military’s confidence when he gave the go-ahead for the nuclear tests and sanctioned other programmes to warm up to the generals. But his outreach to India for peace in the subcontinent led to the Kargil conflict in 1999 and, ultimately, his ouster and banishment by Gen Pervez Musharraf, an army chief he had hand-picked over other senior generals. His third stint from 2013 too, fell foul of the army, because of his public attempt to put Musharraf on trial for high treason—a crime punishable by death or life imprisonment.

While the Musharraf issue was sorted out when the army got Sharif’s government to lift the travel ban on the former president and allowing him to leave for Dubai in 2016, ties between the two sides were irrevocably strained. The last straw was the leak to the media of a closed door meeting where Nawaz berated the army, especially the ISI chief, for not taking action against terror groups like LeT and JeM, which was tarnishing Pakistan’s image.

Interestingly, Kashmir did not play a role—on that sacrosanct issue Nawaz was as hardline as the army. “On Kashmir, Nawaz and the Pakistani army are on the same page,” says former MEA secretary Vivek Katju. The difference between the two resurfaced over restoring peaceful ties with arch-rivals India. “Nawaz surely thought he can segregate the Kashmir issue from that of peace with India. The army had other ideas,” points out Katju.

How does Nawaz Sharif bide his time now? “While protecting the constitution, we can’t destroy the nation; however, the constitution can be slightly ignored for protecting the nation,” said Musharraf to mediapersons in Dubai, while commenting on the evolving situation in Pakistan.

If his cryptic comments are anything to go by, one should not be surprised if attempts are made by the generals to keep aside the Sharifs and prop up someone like PTI chairman Imran Khan. The former cricketing icon-turned politician had been waiting in the wings for some years to be noticed by the army. Perhaps, he can now take over an old, venerable role from the Sharifs, don a premier’s gravitas and play it for the army establishment.