A giant heart in gaudy pink, radiating silver blue rays, throbbed vigorously on the screen behind. Two young couples, dressed in black, danced suggestively to a soft melody on the dimly-lit stage. But the music was suddenly disrupted by shouting and sounds of gunshot. A couple of terrorists, cloaked in green burqas and carrying glow-in-the-dark plastic guns, jumped on to the stage—firing in the air and forcing the hapless foursome into a huddle. They hollered in Arabic and guffawed like villains from bad movies. But before long, a group of sprightly American Rangers came out of nowhere and kicked their asses with Chuck Norris moves, saving the day. The bemused audience clapped in appreciation.

Mid-October evenings aren’t terribly cold in Edison, New Jersey and so the 2,000-odd Indians who had gathered for the ‘Hindus for Trump’ gala—setting of the above show—could display their embroidered salwars and colourful churidaars. Many were Telugus, and they hadn’t come there as much for the politics as for watching Prabhu Deva. Malaika Arora Khan was another big draw. But the biggest name on the ticket was The Donald himself. Three weeks before the presidential election, in the middle of the campaign of his life, he came. He saw. And he conquered with these words: “I am a big fan of Hindu, and I am a big fan of India—Big, big fan.”

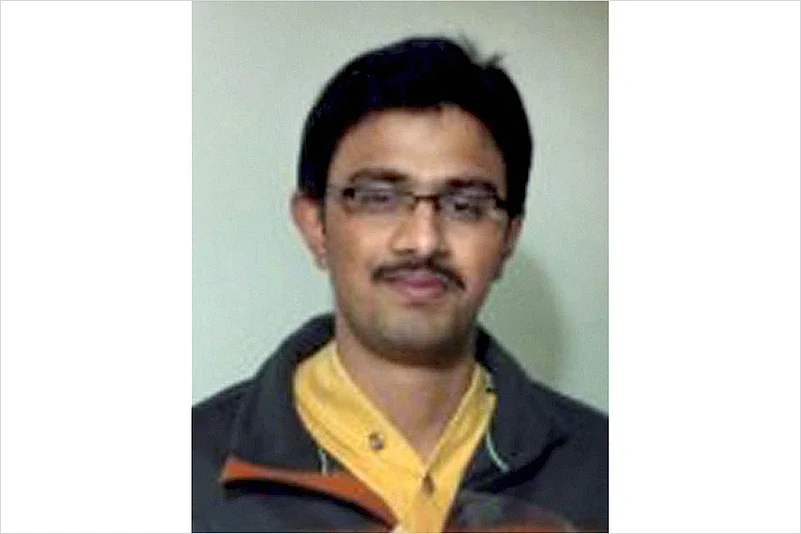

Alok Madasani with wife Reepthi at a prayer vigil in Olathe, Kansas

Indians in America, or at least a rich and visible section of the community, have looked upon Trump as one of their own. They found common cause with his religiously-tinged hyperbolic nationalism; it reminded them of someone closer home. Shalabh Kumar, chairman of the Republican Hindu Coalition that organised the Edison event, contributed close to $1 million to the Trump coffers. The organisation later launched a $400,000 digital ad campaign for him, with its slogan, ‘Ab ki baar Trump sarkaar’, echoing the refrain that catapulted Narendra Modi to power. Many Indians were also hoping that Trump, a businessman first and foremost, would make it easier for Indian professionals working in the Silicon Valley to get green cards.

Things haven’t worked out quite as expected. A series of bills have been tabled in Congress, targeting the visa category that Indians predominantly rely on to work in the U.S. In addition, the Muslim-baiting xenophobia that so endeared Trump to Hindu-nationalist Indians here quickly showed its true colours. A tide of white supremacism started mounting almost immediately after Trump’s victory, inundating minorities of all hues in its wake. The Southern Poverty Law Center reported more than 1,000 ‘bias-related incidents’ in the first five weeks after the November 8 election—or almost 30 every day. Most of these were directed against Blacks, Muslims, lesbians and gays, or immigrants in general. Now, Indians too have become targets.

Srinivas Kuchibhotla

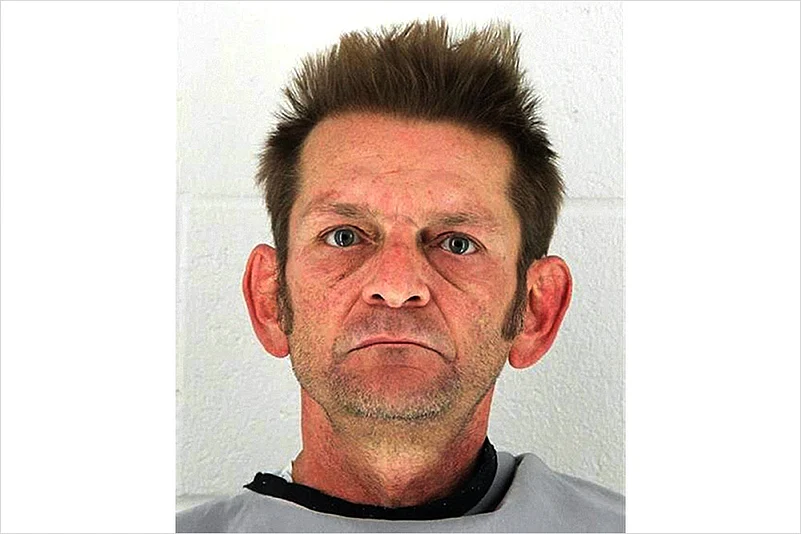

Srinivas Kuchibhotla and Alok Madasani, two 32-year-old Indian engineers working for the technology company Garmin, were shot at on February 22 inside a bar in Olathe, Kansas. The suspect, Adam Purinton, 51, had reportedly been throwing racial slurs their way, shouting, “Get out of my country”, and had been asked by the Austin’s Bar and Grill staff to leave. But he came back with a gun in hand and started shooting at the two Indians. Kuchibhotla was killed. Madasani sustained injuries, as did Ian Grillot, an American patron who tried to intervene. Purinton, a US Navy veteran, was charged with murder.

Local Indian residents say the news came as a shock to them, especially because they have always felt safe in this part of Middle America. “When we heard about it, we were all very scared,” says Parvati Chillara, a private information technology consultant from Overland Park, a seven-minute drive from Olathe. “I have lived here for 20 years and I think I heard something like this for the first time.”

“It was really scary,” says Chinmay Ratnaparkhi, a Master’s student of computer science at the Kansas University in Lawrence, about half an hour away. Ratnaparkhi, 23, arrived here at the start of his undergraduate education and has lived in the area for almost five years. “I haven’t heard anything like this in Kansas. It was very shocking. I didn’t know how to react.”

Ratnaparkhi is the president of the Association of Indian Students at his university. When he learnt about the Olathe shooting, he spoke to other Indian students. “The most common response was anger,” he says. “People are getting frustrated. Why is this happening? People are becoming more intolerant towards people of colour.”

Chillara, too, is a community leader, presiding over the India Association of Kansas City. She heard the news the morning after, when a colleague who had visited the bar to help out following the shooting informed her. She later met with Madasani’s wife to offer support. Her association also organised a peace march and vigil on February 26. Speakers included friends of the victims as well as political leaders and administrative officials. Priests from multiple religions offered prayers.

Adam Purinton

But Ratnaparkhi asks, “We can have peace marches and candle-light vigils, but how do you really protect Indians?” The shaken Indian student community is planning to start a ‘buddy system’ in which students will accompany each other, especially at nights, he adds. “We shouldn’t walk around alone at night. Also, if you feel somebody is making undue comments, don’t react. Withdraw, instead of getting into a fight.”

The Indian embassy in Washington DC did not comment, although it tweeted a photograph of ambassador Navtej Sarna with Kansas Senator Jerry Moran along with the message, “Appreciate that Senator @JerryMoran of Kansas met Ambassador @NavtejSarna to express condolences on death of Srinivas Kuchibhotla”.

Four months after avowing his affection for Hindus and Indians, Trump remained silent. There was more silence from the White House, at least in the beginning. As voices blaming the murder on Trump’s espousal of white supremacism and anti-immigration policies grew louder, a White House spokesperson eventually refuted the charge. This lack of reaction was in marked contrast to the Trump administration’s response to vandalism at a Jewish cemetery in St Louis, Pennsylvania, a week earlier. Trump called the attack and threats to Jewish community centers around the country as “horrible”. Vice President Mike Pence visited the cemetery and said: “We condemn this vile act of vandalism and those who perpetrate it in the strongest possible terms. We saw firsthand what happens when hatred runs rampant in a society.” He then rolled up his sleeves and proceeded to help out with the clean-up efforts.

Trump and Pence have thrived on xenophobia. They have come to power ratcheting up racism. But if Pence’s words from St Louis aroused a sardonic grin, there was more black humour in store for Indians. Purinton, the Kansas gunman, reportedly said he had shot “Iranians” after the attack on Kuchibhotla and Madasani. But this was not simply a case of mistaken identity. Purinton and his ilk don’t really know—or care about—the difference between Indians and Iranians. Even as Hindu-nationalist Indians in America fall head over heels trying to socially engineer kinship with white supremacists by invoking their shared distaste for “Muslim terrorists”, the likes of Purinton don’t see them as any different from Muslims or any other ‘outsiders’ polluting their white country.

To be sure, more than half of America did not vote for Trump in November. It’s the same America that has been rising in revolt against his presidency—spilling into the streets to protest his election, his inauguration as well as his anti-immigration policies. It’s the America that Grillot the Brave, for instance, belongs to. A stranger to Kuchibhotla and Madasani, he had initially defended them from Purinton’s jibes. When Purinton returned to shoot, he tried to intervene again and was badly wounded.

He is hardly alone. The First Baptist Church of Olathe, across the road from the bar where the shooting happened, organised a candle-light vigil two days after the shooting. “The local community has been very supportive,” Chillara says. “Almost all non-profit organisations came together and said they wanted to support the Indian community.”

Ratnaparkhi says he has received similar support from his American friends. “All my local friends were shocked by the incident. I received a lot of calls from them. They wanted to make sure I was feeling safe. They tried to comfort me, and ensured me they are with me.”

For such Americans too, though, there is probably not much difference between Indians and Iranians, or between Hindus and Muslims. Just the weekend before the Kansas shooting, a passenger in a Chicago-Houston flight caustically asked a Pakistani Muslim couple placing their luggage in the overhead bin, “That’s not a bomb in your bag, is it?” As he kept trying to provoke them, other passengers stood up for the Pakistanis and alerted the airline crew. The man making the jibes was asked to deplane “for making others feel uncomfortable”, according to media reports. “Get out of here,” another woman in the plane said. “Racists aren’t welcome in America. This is not Trump’s America. Gooodbyeee raaacists!”

Harassment of Muslim—or Muslim-looking—men and women has been common on American flights for years. Until now, airlines have almost always asked their Muslim passengers to leave the plane “for making others feel uncomfortable”. Neither flight crews nor co-passengers have come to anybody’s rescue. But the Chicago incident shows that, just like their white supremacist compatriots, liberal Americans have also been invigorated by Trump’s victory. There is a growing sense that the idea of multicultural America is under immediate and serious threat—and it is up to common Americans to rescue it.

Unfortunately, Indians themselves don’t always realise that as a community of colour, they aren’t viewed all that differently from other minorities—neither by white supremacists, nor by white saviours. Many Indians speaking to the local media chose not to blame Trump and his rhetoric for the Kansas shooting. But this was not because attacks on immigrants have always been a bane of American society. Instead, they said this was a one-off incident—betraying obliviousness to the unceasing violence against other minorities around them.

They have hailed Grillot as a hero; perhaps they would look up the video the 24-year-old posted on YouTube from his hospital bed. “I was doing what anyone should have done for another human,” he says. “It’s not about where he was from or his ethnicity. We’re all humans.”

The senseless, 1959 murders of the Clutter family—basis of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—had shocked Kansas. A repeat of Kuchibhotla’s murder, actuated by a perverted sense, now has Americans like Grillot to contend with.

By Saif Shahin in Ohio