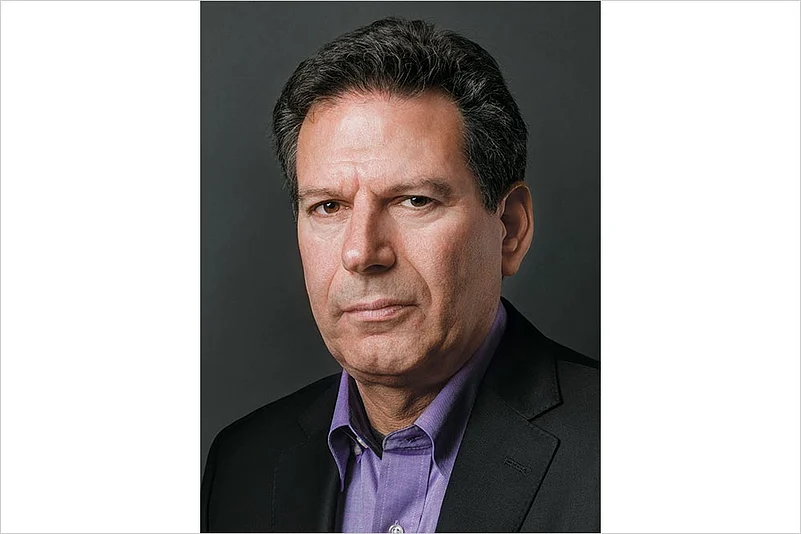

Robert D. Kaplan is one of the best known commentators on geopolitics of our time. He is the writer of 16 bestselling books on foreign affairs and travel. Kaplan was twice named among the top ‘100 global thinkers’ by Foreign Policy magazine and his books have been translated in several languages. At 64, he is one among the four most “widely read” Americans, along with Francis Fukuyama, Robert Kennedy and Samuel Huntington. He is currently a senior fellow at the Center for New American Security and a contributing editor at The Atlantic, where his work has appeared for three decades. Kaplan was the chief geopolitical analyst at Stratfor, a visiting professor at the United States Naval Academy and a member of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board. He spoke to Pranay Sharma on the Indo-Pacific region and how US policy is likely to play out vis-a-vis other key international players under the Donald Trump presidency. Excerpts from the interview:

Governments around the globe are reaching for the reset button to recalibrate their foreign policy since Trump’s victory. How much will it change the US’s foreign policy?

American foreign policy often changes dramatically under a new president. There is less continuity in American foreign policy than in other countries. But there has been continuity in the Indo-Pacific policy since Nixon went to China and in the policy towards East Asia and to a lesser extent on the Indian Ocean.

How will it play out under Trump?

Trump has no inner corps in terms of foreign policy. So it is important who his top advisors are. In terms of interpreting what American foreign policy is going to look like, I think Trump’s election is a symbol that the globalisation that went on for a quarter century since the fall of the Berlin Wall has played itself out. Now there is a backlash from those who have not benefited as much. We have seen it in Brexit or the Polish elections. But America is the most pivotal power in the world and, therefore, I would call this a ‘chapter break’ in post-Cold War history.

But people have questions about this new leader, a rank outsider with unknown policies. They are worried....

Yes, first of all, he is not really a Republican. This is the first time since the mid-19th century that America has had a president whose worldview does not fit in either of the two parties, also he has never been in politics before, which is something new. There is a further point; it’s cultural—Trump’s demeanour is vulgar; it’s not elegant, it’s not sophisticated in the way of former US presidents. Trump is altogether different in cultural terms. So the elites, and educated, sophisticated and cosmopolitan people around the world and in the US could not imagine somebody like this could be elected president. And because they could not imagine it, they thought this would not happen. Well, it has happened.

When Barack Obama diverted focus away from Iraq and Afghanistan with his rebalancing policy in the Asia-Pacific, it was an acknowledgement of the region’s importance as the fastest growing economic and trading entity of the world. Will it change under the Trump administration?

I don’t think it will. The key dynamic to watch is how American relations with Russia change in a way that it might affect America’s relation with China. If, and I emphasise on the word ‘if’, Trump moves closer to Russia that will put pressure on China. Russia and China are not allies even though they both have an authoritarian regime. They compete fiercely in Central Asia; they have a long border that have had many disputes over the centuries and Russia cannot enter into an alliance with China where it will be the junior partner; Russia cannot tolerate that. So a key dynamic to watch is America, Russia and China.

What about the Indo-Pacific?

I don’t think there will be a shift away from the Asia Pacific, or the Indo-Pacific as I liked to call it as I like to include the Indian subcontinent within the power dynamics of East Asia. I think Trump is no more likely to get into a war in the Middle East than President Obama was. The US has already committed significant forces in the fight against ISIS. I don’t see America’s involvement in the Middle East going up that much. And the internal problems of European Union are those which the US cannot really alleviate or deal with; these are internal European dynamics. So, by the process of elimination, the US will continue to focus on the Indo-Pacific.

A major part of the rebalancing was also acknowledging China as the US’s main strategic competitor from which it can face the toughest challenge in the 21st century. How will Sino-US relations pan out?

Trump has threatened a trade war with China and he has also been against the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). Now, ironically, the TPP will be the strongest American weapon against China. Having a free trading regime among America’s allies in the Pacific would be the best kind of balance against China. But Trump is against that and at the same time he wants to limit Chinese power. There is a big contradiction in that obviously and we will have to put aside Trump’s campaign rhetoric. I think there will be a lot of rhetoric in terms of limiting Chinese imports to the US. But I don’t think Trump will actually go through with a trade war with China. That would be too destabilising.

How does he plan to deal with China?

He wants to build up the navy, given that he wants to increase the military budget the naval pressure on China will continue. When an American president says he wants to increase the military budget what he is really talking about is the navy and the air force, because they have these big super-expensive platforms—aircraft carriers, submarines, destroyers etc that cost a lot of money. So with a bigger navy the pressure on China is going to increase. But at the same time the US will not go through with an actual trade war.

Mao and Nixon’s ice-breaking 1972 meeting in China’s capital

Countries like Japan invested heavy political capital on the TPP. If it is dumped now what will be its impact and since it was mainly aimed at China, how do you think Beijing will react?

This is a big problem for the incoming president. The Japanese really took a lot of risk for the TPP and so did others. It was America’s signature element for containing China and particularly useful because it is non-military. It is a peaceful element for increasing world trade that also serves to manage China’s rise. If TPP is dead, that to me is a real benefit to Chinese power projection in the Indo-Pacific. Of course TPP may not be dead, it may change and get a new name. Trump and the Republican Congress may combine it with measures to protect American workers and we will find out in two years or less if a new version of TPP is going to pass. That’s possible.

If changes are brought in the TPP, could other countries also follow the US’s example and bring about changes to protect their domestic workers and business lobbies?

I think there is no way to spin something altogether positive out of the collapse of the TPP. It is a real failure for the Obama administration. It is a failure for the pivot to Asia. The pivot to Asia or Obama’s Asia policy all in a way rested on the passage of the TPP. But I think there was too much of complacency and this attitude of course is going to pass because all reasonable, cosmopolitan people like us want it to pass. This was the Washington elite talking and what turned out was that they had no conception whatsoever of the mood inside the country.

For the better part of 2016 there was a lot of tension in the South China Sea—a region whose importance to China you have compared with what the Greater Caribbean was to the US. Can you explain how?

There is nothing the US or anyone can do that will convince China to dramatically change its policy of increasing its power projection in the South China Sea. From Chinese geopolitical perspective, expanding power in South China Sea makes perfect sense. Over the decades, China has consolidated its hold over its own continental landmass. It’s next turning attention into its adjacent ‘blue water’ extension of the landmass, which is the South China Sea, exactly as the US did with the Caribbean after it consolidated the western part of the American continent in the late 19th century.

How does this help China?

The dominance or parity with the US navy in the South China Sea allows China more easy access for its navy and commercial ships into the outer Pacific and, more importantly, into the Indian Ocean. If China can dominate or be equal with the US navy in the South China Sea, it can go from being ‘one-ocean navy’ in the western Pacific, which makes it a regional power, to being a ‘two-ocean navy’, with merchant fleets in both the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, which makes it a global power. What China is doing makes perfect sense from its historical point of view.

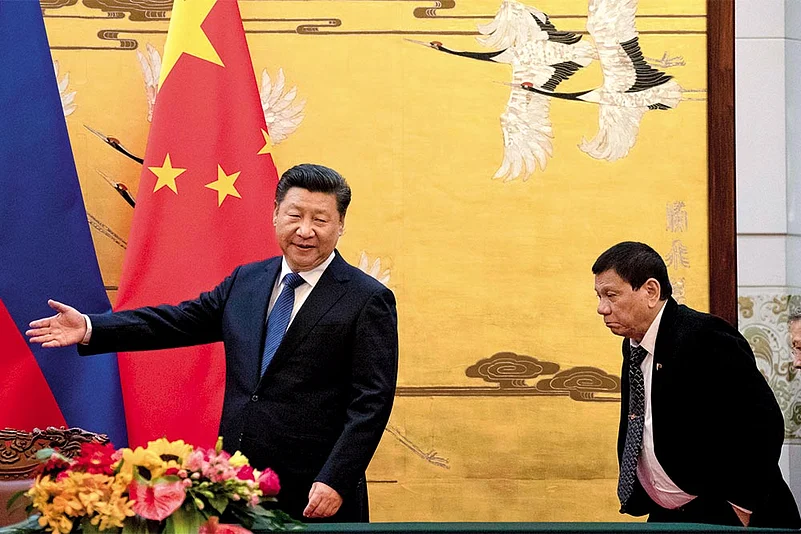

China’s Xi Jinping shows the way to Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte in Beijing

US dominance of the Caribbean took place when most European powers were already out; its attempt was to ensure they do not return to the region. But South China Sea has a number of powerful countries who contest and will continue to contest Chinese domination in the region. How difficult will it be for China to move ahead?

Yes, there is a significant difference between the greater Caribbean and the South China Sea. The similarity is mainly geographical and, therefore, geopolitical. In terms of the power relationship they are different. The European powers were gradually losing influence in the greater Caribbean through the course of the 19th century. Whereas in the South China Sea you have the United States and its allies unwilling to give the Chinese navy significant naval influence. Here is the serious, real maritime and naval struggle for our time in the western Pacific.

So how do you expect it to play out?

The US navy’s Seventh Fleet, which has essentially made the western Pacific an American lake since the end of WWII, has to make room for growing Chinese naval power. They will simply have to make room because China is a ‘rising’ or ‘re-rising’ global power. At the same time it cannot allow this rising power to be dominant. So what is the happy medium—how can the US navy satisfy the Chinese navy without allowing it to gain dominance? What is that happy medium for stability in western Pacific? Rather than a unipolar naval power regime in the western Pacific, as was the case for many post WWII decades now, because of the ascent of the Chinese navy we are now going to have a multipolar power regime.

But the Asia Pacific has a concentration of several political and economic powers. Is it likely to become the new battleground of the world?

I don’t think there will be one new battleground; I think there will be several. The world is entering into a comparative period of anarchy to replace the stability of the Cold War and the post-Cold War era. This means more regional struggles in the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, in the Indian Ocean, in the choke points of the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea and of course in the South and East China Sea. What makes all this very dangerous is that because of technology the world is more interconnected than ever before. Each one of them now has the potential to interact with every other crisis like never before.

How will countries like Japan, South Korea, Vietnam respond? Do you see them having more space for manoeuvre?

I see the importance of Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, India etc is getting greater and greater because of what I call the merging Asia power web. Whereby India has better ties with Japan and Japan has better relations with Vietnam, while India has better relations with both Vietnam and Australia. With each of these countries aligning with each other, it can lead to the emergence of balancing and managing the Chinese power.

Can there be a conflict in the Asia Pacific by an accident and, if so, what can cause it?

Well, you have fighter jets, the ships, cyber war that is being played out by both sides. You can have miscalculations. A plane shot down; a ship that fires on another ship, a cyber attack from China or somewhere else that gets out of hand and suddenly you have an incident. Remember, major conflicts often emerge from small things. But small things illuminate the tension that had been rising for a long time. So there can be an incident in the South China Sea, for instance, that ratchets upwards to a military conflict.

How do you see the Philippines? It is a country that went to the International Tribunal against China but, with a change in government in Manila, also started changing its stand against Beijing. Will more countries now dilute their anti-China stand or will the competition get stiffer?

The situation is really in a flux. The Philippines was an indication that we can talk on and on about geopolitics, but that’s only 50 per cent of the reality. The other 50 per cent is Shakespeare—in other words, individual drama, individual personalities that are more unpredictable than geopolitics. So the rise of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines is an example of Shakespeare, showing that it is just as important as geopolitics. Now, there is an interplay between Shakespearean personal drama at the top of the leadership level and geopolitics. For instance, Duterte has a problem with the Scarborough shoal; he would like to get the Chinese off from some of these geographic features in the South China Sea that the Filipinos claim. He may have been a bit cynical about the US power, that the US talks a good game but it is not there when you need it. Look at what happened with TPP. So, his calculation may have been both born out of his personal experience and also out of geopolitical calculation that he has to make peace with China, because he feels he cannot completely depend on the US.

What about the other countries in the region?

The larger situation is that given the emergence of Donald Trump as the next American president nobody knows what his Asia policy is going to look like, not just the Philippines but a number of countries are very nervous. Over the first six months or year of the Trump administration if they see, for example, that the US is continuing its policy of putting naval pressure on China or coming out with some sort of replacement for TPP or trying to, well then there may not be a change. American allies will feel compensated, they will feel reassured. If the opposite happens and if Trump does not confront China in the naval sphere, if TPP is really dead, if trade tensions between China and the US do increase, well then, you may have more examples of the Philippines in East Asia. More countries would be making quiet side-deals with China because they are uneasy with the policy of this new American president. And then the power balance will shift.

What role do you see India playing?

I think India is emerging, and will continue to emerge as the key pivot state in world politics. We can forecast all kinds of scenarios for China—it is not democratic and its autocracy can conceivably collapse or dramatically weaken; it’s a regime, a Communist dynasty that only has legitimacy because it can improve people’s lives. But if that’s not happening then we can see real internal turmoil inside China. That’s not the case with India. It may have very disappointing governments, it may be extremely frustrating, where nothing seems to get done, but the basic political stability of India is not in question. India will be crucial simply because of where it is and because of the size of its economy. India is a natural hedge or balance against China. This does not mean that India has to have hostile relations with China; it can have very friendly relations with China, but it is still a hedge against China, an alternative great civilisation and a great economy also in Asia.

You think competition with China can act as a catalyst for India to perform better?

It could happen and it should happen because the challenge of China from the Indian point of view should be: how can we get more highways to the airport built; how can we get more roads built, how can we lessen our bureaucracy and build our institutions and make them more streamlined, make it easy for people to invest from outside and how to build our institutions and economy more powerfully so that they can compete more with China. In other words, it is how to make government more effective than it has ever been without losing India’s democratic tradition.