It began with the strategic contraction of the United States. After Osama Bin Laden’s death, the Global War on Terrorism no longer seemed so compelling. Senior leaders in the US began to call for the US to withdraw quickly from Afghanistan, foreclose aid to Pakistan, and bring the troops home. Pressure to attempt to rebalance the US budget led to very significant cuts. With the US close to defaulting on its loans, power projection seemed like a luxury, and many of the programs envisioned by the Pentagon to stay relevant had to be cancelled. The US military bases in the Pacific were not strengthened. A new long-range bomber was not procured. The procurement of the Joint Strike Fighter was cut in half, raising per-unit costs and alienating many partners. None of this helped, and some even hurt the market, and despite deep budget cuts, the US was in decline.

In this period, China and India’s economy chugged along strongly.

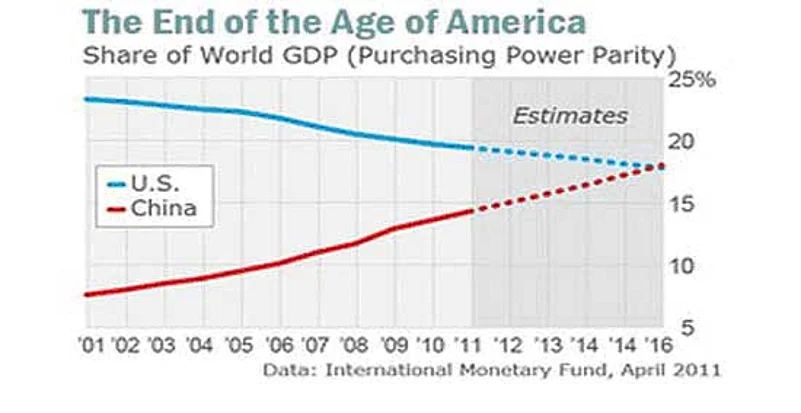

Then things went haywire in a single year. In 2016, the Chinese economy surpassed the US as the largest economy in GDP PPP (Purchasing Power Parity). China’s arguments for an alternate currency were gaining ground. The US was not able to keep up with China. A crisis of confidence occurred in the US. Both countries tried to show their relative strength in a crisis in the South China Sea, threatening both military and financial hostilities, and suspension of trade. A limited but significant series of hostilities commenced.

The US lost a carrier and Okinawa, China lost most of its blue water navy. It did not escalate beyond that. But the stock market crashed.

The US defaulted on its loans. The US economy crashed. Due to its inter-dependent relationship with the Chinese economy, the latter also crashed. Having reached the peak of its demographic dividend and the crest of an unprecedented government-driven push in fixed capital investment, coupled with the loss of the export market ensured there was no way for China to crawl back to positive growth.

The Chinese regime, no longer able to maintain GDP growth, fragmented from within, splitting apart like the former Soviet Union. There was no central government to prevent the secession of Xinxiang or Tibet, and when ethnic cleansing started in these areas, India felt it necessary to intervene —as it had in 1971 to prevent further killings in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) — establishing a truly autonomous Tibet.

With Europe barely able to sustain a ‘No Fly Zone’ over Libya, China consumed with its own internal fragmentation, and the US so economically strapped, India was left as the only large power with meaningful power projection capability.

Though Pakistan tried to exert influence to re-Talibanize Afghanistan, it only served to start a proxy war against India, Iran and Russia. Afghanistan fell to civil war, and overwhelmed Pakistan with armed Pashtun refugees.

Pakistan was now bereft, without the sponsorship of either the US or China. The ISI and terrorist groups were marginalised. India’s comparative success led to a greater appreciation from, and attraction for, the civilian population and heightened the feeling of threat in the army. However, the loss of funding caused a contraction and the resultant internal fragmentation in the defence forces.

Within less than a decade, India suddenly found itself the sole inheritor to the crumbled empires of the British and Americans. Sitting in the central position of the former British Raj and its vast Indian Ocean trade network from West Asia to East Africa to Australia, Singapore and Malaysia, India had sufficient power projection assets to range coast to coast. That India had cultivated all the US allies—Japan, Korea, Australia —who still remained unitary and functioning economies, also helped.

The UK and the US were only too happy to cede the usage of Diego Garcia, Bahrain, Mazar e Sharif, Kabul, Qatar, and Tajikistan to India. The US was even in a hurry to sell of significant elements off its Air and Naval Force structure.

It was a relief to most in the world that someone was still able to maintain some order and keep the global commons and pipelines open to allow continued trade of oil and goods. India proved itself to be a relatively benign hegemon, following the open trade practices in the commons of the British and Americans.

Without the ideological impedance of Pakistan or the border dispute near Tibet, and with a cooperative Iran, India was able to reconnect the vast Silk Road trade networks connecting Sinic, Indic, Turkic, and European cultures into a vibrant central artery of trans-civilisational commerce after a long time.

Quite by accident, India found itself to be the pivot of the world, and the only power capable of sustaining global commerce and committed itself to the following principles:

- The international system will continue to be based on the Westphalian system of nation-states. Hence, relationship with other states will be based on sovereign equality and territorial integrity.

- The international system will be democratic, pluralistic, and multi-lateral. Indian history and cultural values of tolerance and pluralistic living will influence India’s foreign policy engagement with other countries of the world.

- India will be non-interventionist in the internal affairs of other states and will aim to resolve disputes through dialogue and negotiation. The use of force for humanitarian purposes will be the last resort.

- India will be an integral part of the international society and work in consultation with others for the safeguard of the “global commons”.

- India will continue to champion the cause of the least developed countries given its own experience of colonialism and anti-imperialist struggle led by Mahatma Gandhi.

Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore had once imagined a world without nationalism, where the safe-keep of the global environment and harmony amongst nations would be paramount. He was a firm believer in democracy and freedom. Based on such a rich spiritual ethos and the example of Mahatma Gandhi, India dedicated itself to the path of human progress.

Dr. Namrata Goswami is Research Fellow at the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. Views expressed here are that of the author and not of the IDSA. The author would like to thank Lieutenant Colonel Peter A. Garretson, Grand Strategist and Futurist, from the US Air-force, Pentagon, Washington DC for providing inputs towards conceptualising this piece.