Small neighbours often find interesting ways to get back at Big Brother. Bhutan, widely believed to be India’s closest ally, may not be an exception to that tradition. The first round of the parliamentary elections in Bhutan on September 15 , that knocked out India’s favoured Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay and his ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP), perhaps has an important lesson for policy planners in South Block.

The shock defeat of Tobgay came five years after India played a key role in ousting Jigme Thinley, the then PM and his Druk Phuensum Tshogpa Party (DTP)by cutting subsidies on petrol and LPG supplies to Bhutan for his growing closeness with China.

Bhutan has a history of being caught between the power play of India and China. In July 2017, it was in the international limelight when Indian and Chinese soldiers were engaged in a 73-day-long eyeball-to-eyeball standoff at the Bhutanese-claimed plateau, Doklam, close to the tri-junction of the three countries’ borders.

However, the rising spectre of war between the two nuclear-armed Asian giants meant the standoff was resolved peacefully without a single shot being fired. But getting caught in another Doklam-like situation remains a concern for policy planners in Thimphu.

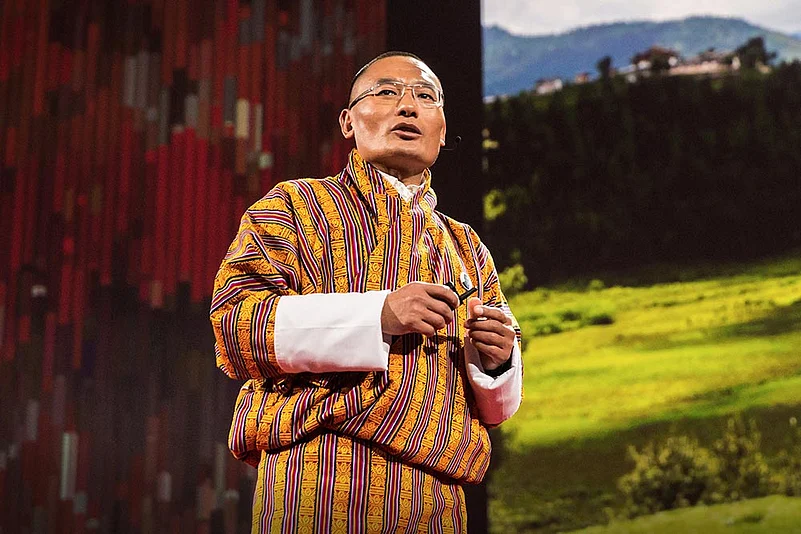

According to the Bhutanese constitution, two parties with the highest number of votes in the first round qualify for the final round, while the others in the fray are eliminated. The Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) Party, led by a charismatic and popular surgeon, Lotay Tshering, came first and the DTP second. They will now fight it out in the final round of the parliamentary polls on October 18.

“It’s difficult to say if there is anti-incumbency mood, but going by the results, people voted for change,” Bhutan’s best known newspaper Kuensel noted.

However, a few weeks ago, outgoing premier Tobgay had told Kuensel, “One of the challenges specific to PDP will be anti-incumbency.”

According to him, if the government, for whatever reason, has failed the people, be it corruption, or on economic and social fronts—that government must be got rid of. “But if it’s a case of ‘let us give somebody else a chance’, that is dangerous—because democracy is not a game,” said Tobgay, whose party held 32 seats in the 47-member national assembly.

Bhutan shifted to a constitutional monarchy in 2008 and this is the country’s third parliamentary election. Going by the growing enthusiasm of the voters—as nearly 66 per cent cast their votes in Saturday’s election, which was more than the 55. 3 per cent registered in 2013—people in this erstwhile Himalayan kingdom seem keen to use their new-found freedom and the tools of democracy.

Observers feel that for the new Bhutanese government, the focus will certainly be on employment generation and finding ways of expanding and diversifying the revenue generating model from the current hydropower sector, dominated by India, to other areas. Though India has not been an issue directly during the election campaign, political players have been stressing on a “self-reliant Bhutan”.

For India, however, it is China, which is the elephant in the room. So far, Beijing does not have an embassy in Thimphu, but is keen on opening one. This, however, has not stopped senior Chinese officials from visiting the country and engaging with the Bhutanese leadership. China wants to finalise a land-swap deal it had been negotiating with Bhutan for several years. Part of the Bhutanese land China wants also include Doklam, a strategically important plateau that overlooks the Siliguri corridor, connecting India’s Northeast with the rest of the country. This remains a serious concern for India.

A new Bhutanese prime minister, when he takes office next month, will have to face the challenge of balancing between its two big neighbours and match Thimphu’s own interest with theirs. New Delhi will require some deft diplomacy to ensure not to upset that balance.