Iraqis cast ballots on Sunday for a new parliament in a vote boycotted by many of the young activists who thronged the streets two years earlier calling for an end to corruption and mismanagement.

The vote had been scheduled for next year but was brought forward in response to the popular uprising in the capital of Baghdad and southern provinces in late 2019. Tens of thousands of people took part in the mass protests and were met by security forces firing live ammunition and tear gas. More than 600 people were killed and thousands injured within just a few months.

Although authorities gave in and called the early elections, the death toll and the heavy-handed crackdown prompted many young activists and demonstrators who took part in the protests to later call for a boycott of the polls.

A series of kidnappings and targeted assassinations that killed more than 35 people has further discouraged many from taking part. Apathy is widespread amid deep scepticism that the independent candidates stand a chance against established parties and politicians, many of them backed by armed militias.

“I voted because there needs to be change. I don't want these same faces and same parties to return,” said Amir Fadel, a 22-year-old car dealer, after casting his ballot in Baghdad's Karradah district.

A total of 3,449 candidates are vying for 329 seats in the parliamentary elections, which will be the sixth held since the fall of Saddam Hussein after the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the sectarian-based power-sharing political system it produced.

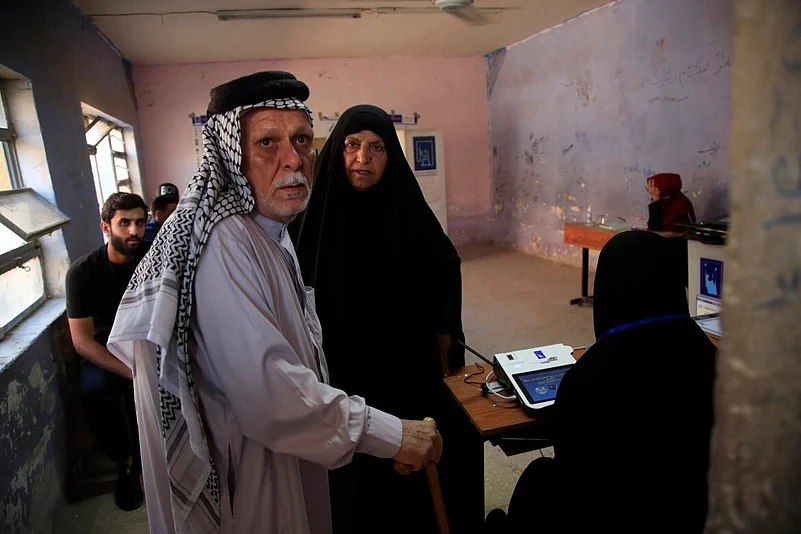

More than 250,000 security personnel across the country were tasked with protecting the vote. Soldiers, police and anti-terrorism forces fanned out and deployed outside polling stations, some of which were ringed by barbed wire. Voters were patted down and searched.

Iraq's President Barham Salih and Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi urged Iraqis to vote in large numbers.

“Get out and vote, and change your reality for the sake of Iraq and your future,” said al-Kadhimi, repeating the phrase get out' three times after casting his ballot at a school in Baghdad's heavily fortified Green Zone, home to foreign embassies and government offices.

The 2018 elections saw just 44% of eligible voters cast their ballots, a record low, and the results were widely contested. There are concerns of a similar or even lower turnout this time.

By midday, turnout was still relatively low and streets mostly deserted. In a tea shop in Karradah, one of the few open, candidate Reem Abdulhadi walked in to ask whether people had cast their vote.

“I will give my vote to Umm Kalthoum, the singer, she is the only one who deserves it,” the tea vendor replied, referring to the late Egyptian singer beloved by many in the Arab world. He said he will not take part in the election and didn't believe in the political process.

After a few words, Abdulhadi gave the man, who asked to remain anonymous, a card with her name and number in case he decided to change his mind. He put it in his pocket.

“Thank you, I will keep it as a souvenir,” he said.

At that moment, a low-flying, high-speed military aircraft flew overhead making a screeching noise. “Listen to this. This sound is terror. It reminds me of war, not an election,” he added.

In the Shiite holy city of Najaf, Iraq's influential cleric Moqtada al-Sadr cast his ballot, swarmed by local journalists. He then drove away in a white sedan without commenting. Al-Sadr, a populist who has an immense following among Iraq's working class Shiites, came on top in the 2018 elections, winning a majority of seats.

Groups drawn from Iraq's majority Shiite Muslims dominate the electoral landscape, with a tight race expected between al-Sadr's list and the Fatah Alliance, led by paramilitary leader Hadi al-Ameri, which came in second in the previous election.

The Fatah Alliance is comprised of parties affiliated with the Popular Mobilization Forces, an umbrella group of mostly pro-Iran Shiite militias that rose to prominence during the war against the Sunni extremist Islamic State group. It includes some of the most hard-line pro-Iran factions, such as the Asaib Ahl al-Haq militia. Al-Sadr, a black-turbaned nationalist leader, is also close to Iran, but publicly rejects its political influence.

Under Iraq's laws, the winner of Sunday's vote gets to choose the country's next prime minister, but it's unlikely any of the competing coalitions can secure a clear majority. That will require a lengthy process involving backroom negotiations to select a consensus prime minister and agree on a new coalition government. It took eight months of political wrangling to form a government after the 2018 elections.

The election is the first since the fall of Saddam to proceed without a curfew in place, reflecting the significantly improved security situation in the country following the defeat of IS in 2017. Previous votes were marred by fighting and deadly bomb attacks that have plagued the country for decades.

As a security precaution, Iraq closed its airspace and land border crossings and scrambled its air force from Saturday night until early Monday morning.

In another first, Sunday's election is taking place under a new election law that divides Iraq into smaller constituencies - another demand of the activists who took part in the 2019 protests - and allows for more independent candidates.

A UN Security Council resolution adopted earlier this year authorised an expanded team to monitor the elections. There will be up to 600 international observers in place, including 150 from the United Nations. More than 24 million of Iraq's estimated 38 million people are eligible to vote.

Iraq is also for the first time introducing biometric cards for voters. But despite all these measures, claims of vote buying, intimidation and manipulation have persisted.

The head of Iraq's electoral commission has said that initial election results will be announced within 24 hours.