For better part of the last century, and almost from the 1920s onwards, when modern journalism turned more professional and into a respectable vocation, the American media and its continental cousins have enjoyed tremendous clout, prestige and influence in countries across the globe.

Their pithy writing, ‘unbiased’ reportage and analytical skills of complex issues, both at home and in faraway conflict and disaster zones, turned them into models and exemplars for journalists and media organisations across the world. But though the western media enjoys a reputation of being liberal, it rarely disclosed the fact that they were also part of the establishment and often worked in its interest.

“The major media, The New York Times and so on, tends to be what is called liberal. Of course, liberal here implies highly supportive of state power, state violence and state crimes,” American thinker Noam Chomsky told Outlook in a 2010 interview.

Others outside the US—particularly in countries that were victims of America’s armed intervention or machinations for regime change—would agree with Chomsky. They often argued that beneath that exalted veneer the western media and their hyped journalists were just glorified pamphleteers of their respective governments.

This view surfaced prominently during the Cold War, when the US-led West was engaged in an ideological battle with the erstwhile Soviet Union. The CIA and the MI5 left no stone unturned—they had jointly sponsored films, including George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, and deliberately changed the ending, ignoring the author’s instructions, to sharpen the anti-Soviet criticism. Then, they funded journals and magazines like Encounter, drawing celebrated names (without their knowledge) like poet Stephen Spender, philosopher Isaiah Berlin and journalist Irwing Kristol. The CIA even orchestrated the publication of Boris Pasternak’s Dr Zhivago in the West in 1957 after it was suppressed in the USSR. It is with stinging irony that Orwell had once said, “Journalism is printing something that others do not want to be printed; everything else is public relations.”

After 2003, mainstream American media’s allegiance to the state became explicit, as it was roundly accused of helping the US government in ‘manufacturing’ consent against Saddam Hussein’s non-existent ‘WMD programme’—thus justifying the invasion of Iraq. Some, like NYT foreign correspondent Daniel Simpson, protested and resigned, accusing the newspaper of having become a “propaganda megaphone”. His lone voice went unheeded; journalists from most major US media bodies scrambled to enlist as ‘embedded’ journalists and travelled with the invading Americans in Iraq, casting doubts about their credibility.

In the past, another war, Vietnam, yielded such classics of conflict reportage as Michael Herr’s Dispatches, with American media coverage deemed by media commentators as having reached one of its high points. Yet, the more critical coverage of the government’s effort came, as highlighted by Neil Sheehan in his book A Bright Shining Lie, only after the 1968 Tet Offensive, with the realisation that the US was not in a position to win in Nam.

More recently, when whistleblower Edward Snowden sought a pardon from the Obama administration, the mainstream media was split. The NYT was for a pardon, but The Washington Post opined that Snowden should be tried for leaking government secrets that jeopardised the US’s position and hampered its intelligence operations.

Throughout all this, the venerated position of the American media remained unaffected. That is, until recently.

Now, a war has been declared on them by US President Donald Trump. This tirade not only threatens to destroy their credibility, but is also aimed at tarnishing the sacrosanct image the media has nurtured for years.

If Trump was vicious in his attack of the mainstream American media (and they of him) during his campaign, he has remained relentless in the severity of his criticism after assuming office. They peddle “fake news” and “only spread lies” has been Trump’s standard charge, as he goes about cautioning the American public about major newspapers like The Washington Post and The New York Times and TV networks such as CNN.

Trump, a rank outsider who managed to win the Republican party nomination and the presidential election against media-favourite Hillary Clinton, has promised to break the Washington establishment and give power back to the American people.

As American academic and social critic Camille Paglia had predicted before the election, “If Trump wins, it will be an amazing moment of change, because it would destroy the power structure of the Republican Party, the power structure of the Democratic Party and destroy the power of the media. It would be an incredible release of energy...at a moment of international tension and crisis.”

Trump has created a crisis not only within the US but deepened a sense of gloom beyond America’s shores, particularly across the Atlantic, where in the wake of last year’s Brexit, the very foundation of the European Union has been put to test. Trump’s victory has increased the possibility that similar right wing and nationalist forces now have a better chance of seizing power in several European countries due for elections this year.

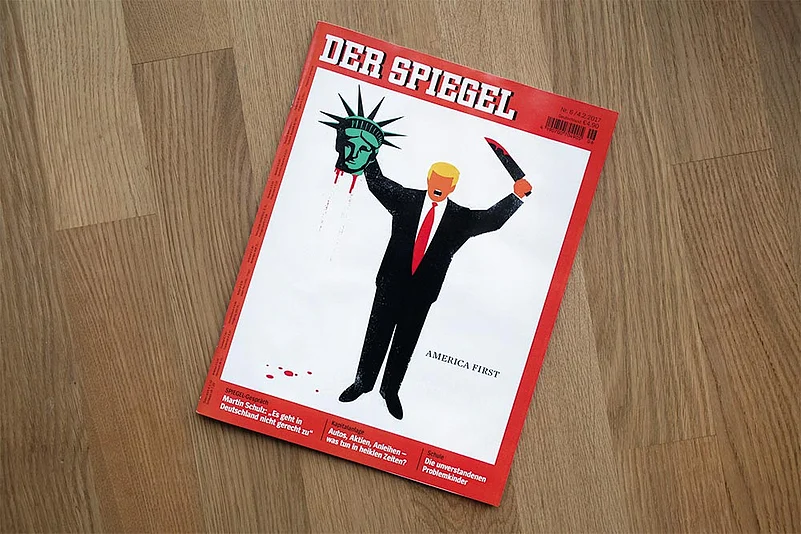

The nervousness among the European liberals, especially its media, has culminated in a counter-offensive against the American president and the threat he poses to hard-won western liberal values. This campaign was encapsulated on the cover of German magazine Der Spiegel that showed Trump holding the severed head of Lady Liberty in one hand and a knife with blood dripping from it on the other.

Other magazines have also voiced their anguish—an Economist cover showed Trump lobbying a Molotov cocktail into the White House, to show how worried they were about the his potential to damage the establishment. But it was the Spiegel cover that sparked off a major controversy, leading many liberals also to question whether comparing an elected US President with IS jehadis was an appropriate thing to do.

Back in the US, the media seems to be facing one of their worst crises. Since Trump’s victory—which most of the mainstream media had failed to predict—their stocks had been falling steadily. The latest Gallup survey shows the media’s credibility—usually consistently over 50 per cent—have now fallen to a lowly 32 per cent.

It is not only Trump supporters who are questioning the credibility of the media, criticism against them is also coming from the left and liberal sections. “What we know as the media never imagined a Trump victory,” says Stanford University historian Victor Davis Hanson. “It has become unhinged at the reality of a Trump presidency.”

Similar views are also expressed by WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who charges the US media with “ethical corruption”, while Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald has described the attempt by The Washington Post to carry unverified reports about Russia’s involvement in the hacking of the email system of the Democratic Party’s headquarters “as an incredibly irresponsible and dangerous form of behaviour that media outlets, led by The Washington Post, are engaging in”.

But the US media and its symbiotic ties with the state is also something that its old colonial masters, the British, had INStituted and used effectively to safeguard the empire’s interest. The case of Hans Raj Vohra, is a point in example. The young revolutionary-turned-approver’s statement in the Lahore Conspiracy case in 1929 was instrumental in sending Bhagat Singh, Raj Guru and Sukhdev to the gallows. The Viceroy rewarded him by arranging his education at the London University and later accommodated him as a journalist at the Civil and Military Gazette.

How will the intractable stand-off between Trump and the mainstream media play out? The recent stay order of the judiciary on the US President’s ban on immigration from seven predominantly Muslim nations is seen as the first major setback for him and, therefore, a victory for the media that had been extremely critical about it.

“The media has now become the opposition party, not the Democratic Party,” Trump’s chief strategist Stephen Bannon complained in exasperation.

Are the claws in this fight going to get sharper, drawing more blood in the coming days? Or will the US media fall in line and accept the new order that Trump is attempting to set up? The American media won’t give up without a protracted bareknuckle fight.