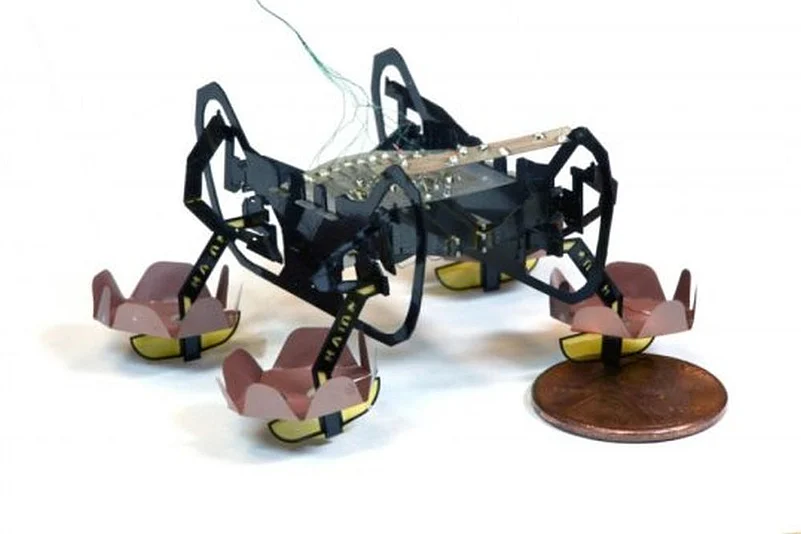

Scientists have built a robotic cockroach that can walk on land, swim on the surface of water, and explore grounds underwater for as long as necessary.

The Ambulatory Microrobot, known as HAMR, uses multifunctional foot pads that rely on surface tension when it needs to swim. However, it can also apply a voltage to break the water surface when it needs to sink.

This process is called electrowetting, which is the reduction of the contact angle between a material and the water surface under an applied voltage. This change of contact angle makes it easier for objects to break the water surface.

The research by scientists from Harvard University in the US opens up the possibility to study new environments.

Moving on the surface of water allows a microrobot to evade submerged obstacles and reduces drag. Using four pairs of asymmetric flaps and custom designed swimming gaits, HAMR robo-paddles on the water surface to swim.

Exploiting the unsteady interaction between the robot's passive flaps and the surrounding water, the robot generates swimming gaits similar to that of a diving beetle. This allows the robot to effectively swim forward and turn.

"This research demonstrates that microrobotics can leverage small-scale physics - in this case surface tension - to perform functions and capabilities that are challenging for larger robots," said Kevin Chen, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard.

HAMR weighs 1.65 grammes - about as much as a large paper clip - and can carry 1.44 grammes of additional payload without sinking.

Once below the surface of the water, HAMR uses the same gait to walk as it does on dry land and is just as mobile. To return to dry land HAMR faces enormous challenge from the water's hold.

A water surface tension force that is twice the robot weight pushes down on the robot, and in addition the induced torque causes a dramatic increase of friction on the robot's hind legs.

The researchers stiffened the robot's transmission and installed soft pads to the robot's front legs to increase payload capacity and redistribute friction during climbing. Finally, walking up a modest incline, the robot is able break out of the water's hold.

"This robot nicely illustrates some of the challenges and opportunities with small-scale robots," said Robert Wood, from Harvard.

"Shrinking brings opportunities for increased mobility - such as walking on the surface of water - but also challenges since the forces that we take for granted at larger scales can start to dominate at the size of an insect," Wood said.