It is always difficult to second guess a large, and reputedly inscrutable, country like China, especially at a time of crisis. Whether standoff between India and China on the Doklam plateau—at Doko-La, on the tri-junction of borders of India, Bhutan and China—where rival soldiers are stationed in close proximity, can be called a full-blown crisis or one in the making would be a matter of debate. But, as the episode enters its second month with no signs to suggest that either of the two sides is willing to yield ground and take the first step to restore status quo ante, people in the subcontinent and beyond have begun to wonder if a second war between the two Asian neighbours is in the offing. The recent live-fire exercise by units of the Chinese army in the Tibet Autonomous Region has spread a whiff of cordite over the crisis, intensifying the war talk.

On the face of it, both sides maintain that they are engaged with each other and the top priority is to resolve the standoff through negotiations. But the relentless, stentorian rhetoric emanating out of China—its government-run media and the foreign ministry—almost on a daily basis has also not failed to remind everyone that an armed conflict remains an option to break the logjam at Doklam.

“Much of China’s harsh rhetoric is a reflection perhaps of some surprise on their part that India actually intervened on behalf of a third country,” former foreign secretary Shyam Saran said in a recent interview. He went on to say that China did not anticipate Indian troops entering the Doklam plateau, a territory of Bhutan. “This is the first real India-China standoff in a third country. Perhaps, China did not anticipate such a reaction from India,” added Saran.

But if the strong Chinese reaction has been because of India’s ‘unpredictable’ response, the growing worry in several quarters now is how unpredictable the Chinese would be to match the Indians?

Sources said that Indian ambassador in Beijing, Vijay Gokhale, had been in regular touch with the Chinese leadership to try and probe if the situation could be brought under control by cutting down on rhetoric and finding a diplomatic solution. Gokhale was in New Delhi recently to brief the Indian leadership about his assessment of China’s stand—it has been insisting that to find a peaceful solution, India should first have to withdraw its troops from Doko-La, an area China claims as its own.

But so far, India’s stand has been based on three principles—hold your nerve; hold your tongue and hold your ground. Which in effect means that despite regular remarks by the Chinese media and thinktank members on the 1962 war and India’s humiliating defeat, India has decided not to match the rhetoric with strident remarks of its own. It has also decided not to blink and, on the ground, to stick to its position. India feels it is the Chinese which broke the status quo by building a road in Doko-La and the onus lies with it to restore the pre-June 16 situation—when Bhutanese and Indian troops noticed the construction, and prevented its expansion.

“I expect a long haul—maybe weeks, months or even longer,” says Ashok Kantha, former Indian ambassador to China and currently the director of the Institute of Chinese Studies in New Delhi.

For Kantha, the most encouraging sign so far has been that troops on both sides have maintained a certain calmness throughout the standoff. “There has been no hostility on the ground at Doklam despite the continued standoff,” points out Kantha. In the light of China saying this week that its patience would not last long, a question arises about the duration of this new, tense status quo. Or could there be an early breakthrough?

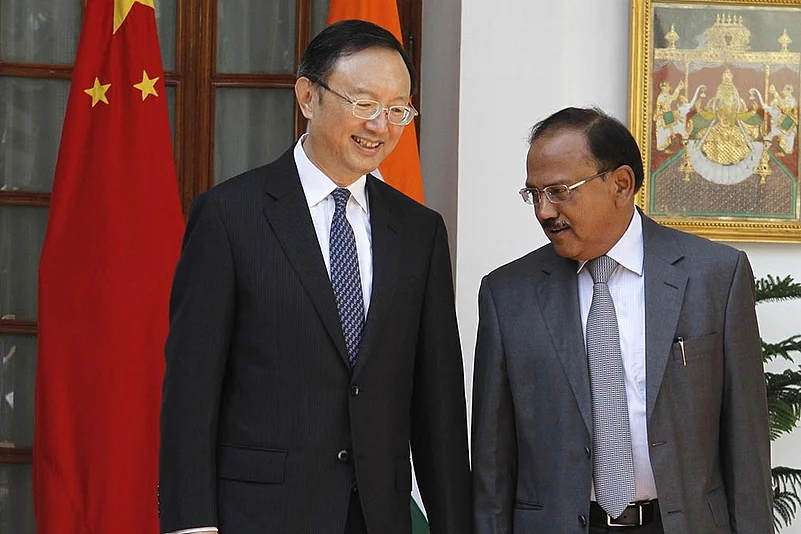

National Security Advisor Ajit Doval would be going to Beijing later this month to attend the BRICS NSA meeting on July 27-28. Indications suggest that Doval, who is also the Indian Special Representative on the boundary talks, would discuss the matter with his Chinese counterpart, Yang Jeichi and try and find a common, agreeable ledge on which a diplomatic solution could be erected.

Amidst the crisis in full bloom, PM Naredra Modi and Chinese president Xi Jinping had a brief but cordial meeting on the sidelines of the Hamburg G-20 Summit some weeks back, expressing satisfaction over their cooperation in the BRICS platform. There was no outward sign of any discomfort over the standoff at Doko-La.

The fact that the Chinese media chose to downplay the meeting between the two in Germany, while the Indians stressed on their cordiality on the G-20 sidelines, had been interpreted in different ways. Though most agree that no one wants a conflict, the possibility of such an outcome cannot be totally ruled out.

Indians argue that though Chinese road construction activities at Doklam have stopped, it could resume the moment Indian soliders withdraw to their original position inside Indian territory. The Bhutanese agree and insist that the Chinese should not only stop constructing the road, but also withdraw their soldiers from what they affirm is their territory. The Chinese reject both these arguments and stress that no movement forward would be possible unless India first vacate Doklam which, they asseverate, is Chinese territory.

Quite possibly, the fate of the standoff is also linked to developments scheduled in China in the coming months. One, of course, is the September BRICS Summit, to be attended by leaders of all member countries, including PM Modi. Some observers feel that the Doklam episode would find a happy resolution by then, for surely it would be terribly odd if the Indian PM were to attend summit meetings with the Chinese president (and other leaders) in China while their soldiers were locked in a tense standoff at the border.

Others, however, point to a much bigger event in President Xi’s calendar in October—the 19th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. That is widely regarded by observers as crucial for Xi, for it would determine if he is accepted as China’s unchallenged leader by his colleagues in the Communist party. If the Doklam standoff drags on till then, it could pressure Xi Jinping to force the issue and make India accept China’s supremacy in the region. This, ominously, could well be decided by engaging in a war with India.

However, if that is one way for Xi to consolidate his position, that strategy is a double-edged sword, containing no surety of a positive outcome. Irrespective of the nature—short or long—of such a conflict, an unpredictable result could irreparably damage Xi’s image. It could also lead China’s wary neighbours, other Asian countries and those beyond to openly distrust Beijing’s claims of a peaceful rise to the top.

Given the intractable problem that the Doklam standoff is turning out to be, a lot depends on Xi’s choice of resolving the matter. There is no guarantee how a war would end, while his ability to sit across with PM Modi to resolve all outstanding issues would surely behove that of a mature politician, one who likes to think of himself as a leader of a superpower with an expanding global influence.