On Sunday, preparations had begun for the start, from this week, of the famous Lahori spring festival, Jashne Baharan, disliked by mullahs but greatly loved and supported by ordinary people. Lights were being put up on trees and colourful banners on the sides of the streets. Despite some rain, kite-flying had already begun in a few mohallas. Tents and stalls were coming up in parks, arrangements were being made for an open air music festival later in the week at the Race Course Park. Tourists, who show up in Lahore in growing numbers to celebrate Jashne Baharan, or Basant, as the festival is more commonly known, had already begun to arrive. The most noticeable were the turbaned Sikhs from the other side of the border.

I spent the evening in the company of Usman Peerzada, a well-known Pakistan theatre personality and actor who organises mega performing arts festivals in Lahore, and the talk was all about growing Indo-Pakistan people-to-people contacts, despite the bureaucratic roadblocks, and all the constraints in the peace process. Last year, he said, out of 675 foreign performers at his World Performing Arts Festival, 185 were from India. "It is unprecedented," he exclaimed.

That was Sunday.

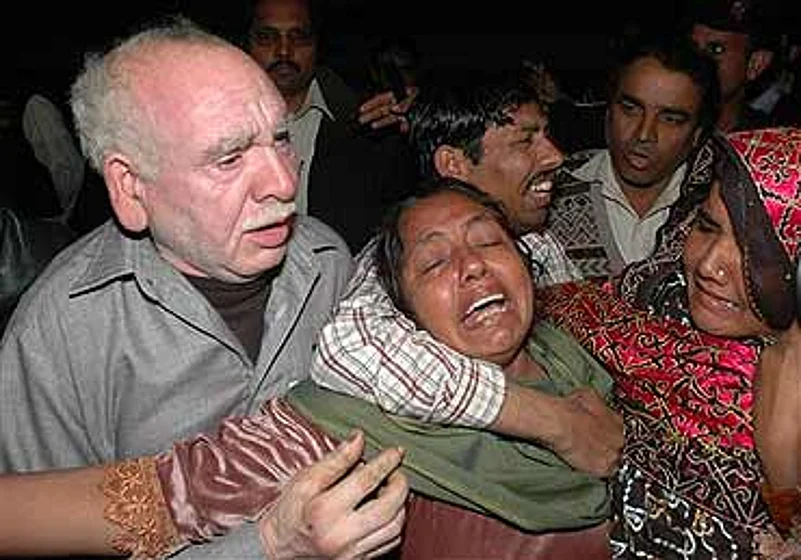

On Monday morning, the optimistic and celebratory mood was shattered, soon as news began to filter through the city about the train disaster. At 10 am in the morning, a counter was up and running at Lahore Railway Station. Ashraf, a rickshaw driver was the first to arrive. His wife, Zahida Parveen, and sons, Kamran and Danial, were on the Samjhauta Express, coming back to Lahore after visiting relatives in old Delhi’s Kabutarkhana market. Silent, grim and obviously frantic, he had little to say, but every now and then he would go up to the counter, repeating the names of his two sons to officials who had alreadywritten them down. Soon, his wife’s sister and other relatives began to show up. But there was no news for them, no news of who had died, none either of when the train would arrive.

As the crowd began to grow around the counter—of relatives, bystanders and the media—the mood was one of bewilderment and confusion. What came throughstrongly—whether at the railway station, or among the shopkeepers in the bazaar that morning, or on the Wagah border, which we had to cross on foot on Monday, to re-enter India before our visas ranout—was a reluctance to believe that Pakistanis could have been involved in the pre-meditated large scale butchery of their fellow countrymen and women on Indian soil. The one or two who did buy that version of events were quick to distance themselves:"terrorists kaa koi mulk nahi hai. [terrorists do not belong to anycountry]".

"Who could have done this?" asked the Pakistani immigration officer at the Wagah border. "Laskhar-e-Toiba?" we suggested. " But what about your Indian groups, you know, your BJP and your Shiv Sena?" he asked. The man was gentlemanly and courteous, and what he said was not an accusation—rather, an inability to cope with the news, and a painful search for answers.

The mood was sombre, as we crossed, not just among the officials, but also among the Indian and Pakistani coolies who carried our luggage from one country to the next. The Pakistani porters wear orange and green uniforms, the Indians blue, but it is only the colour of their uniforms and their nationalities that sets them apart. Their stories are the same: small farmers and landless who hail from villages either around Attari, on the Indian side, or Wagah, on the Pakistani. Their job ends at zero point, and none have been to the country across the border—the poor don’t get passports easily, they point out. And both are grateful for the income that a smoother flow of traffic on the border, of passengers and goods, has brought. Their day is spent carrying the luggage of passengers and unloading the painted trucks from Kabul, bursting with dry fruits for India, or the Indian trucks stuffed with sacks of onions and vegetables bound for Pakistan. When the sacks shift from Indian heads to Pakistani heads, or the other way around, at zero point, the heads almost meet. Almost, but not quite. And for both the men in orange and green, and those in blue, the news of the train disaster brought the same worries: slowly, life was getting better on the border, where it’s not easy to earn a living. Let nothing please derail that.

Passing through Wagah was easy, despite the train disaster, but at Attari railway station, a short while away, the scene was very different. The ill-fated train, divested of its burnt coaches, had arrived, on its way to Lahore, but there was no news of when it would leave. On the platform, among rows and rows of immigration counters, were small groups of passengers, shaken and traumatised by what they had seen and experienced. Once again here, was the inability to make sense of the news, or to believe that it might have been the work of fellow Pakistanis. "There was no blast," insisted the group from Karachi. " All that happened was that the train caught fire." "Jab se train chali hai, jalne saRne ki badbuu aa rahii thii. LogoN ne chainkhiinchaa, poochaa yeh kyuuN aa rahii hai. Zaroor koi short circuit huaa hogaa,gaaRi mein koi fault hogaa, aur kuchh nahi kahaa jaa saktaa, [From the timethe train started, there was a smell of burning. People pulled the chain andasked what it was because of. Certainly there must have been a short-circuit orsome other fault in the train. Nothing else can be said]" said Muqqadas Anisa, one of the group. The sentiment was repeated again and again by others who had been in coaches distant from the ill-fated one. "Kaun kehtaa hai ke blast huahai? Who says that a blast took place?"

But Bhuri, an Indian citizen from Meerut, and Zeenat Shafiq, from the Pakistani side, knew differently. Both women had been in coach 11 and had survived to tell their story, with a few burns and minor injuries. The soundbites had been given, the local camera crews had come and gone, and now they were being examined by the Medical Superintendent from the Railway Hospital in Amritsar. Haltingly, the women talked, remembering the other families sitting around them, the women opening theirdabbas to take out their rotis for the evening meal, and the children playing, until the blast ended it all. "Uske baad koi apne maa ke liye ro raha tha, koi apne bache keliye, [After that someone was crying for their mother or for their children]" said Zeenat, breaking into sobs. Bhuri, a widow, had two traumas to deal with. Her daughter, married into a Lahore family, had just died in Pakistan, and she was travelling there to help look after her grandchildren. Sometimes, she was silent and composed, but every now and then would get agitated, remembering something new. Suddenly, she got up from the sofa and stood before the customs official, pleading, " paanch dus kilo ka samaan tha mera, woh be chala gaya, kuch keejiye mere liye,saab. [All I had was baggage of 5-10 Kgs, but that too is gone, please dosomething for me, sahib]". But there was no question of going back home to Meerut, and no choice but to continue on the train. "I am needed there, I can’t go back," she said.

It was the same for the rows of Indian Muslims waiting patiently to board the Pakistani-bound train from Attari. Unlike most of the passengers on the train, they had seen the charred bodies on TV, they knew the details. But they were going, because there were things to be done in Pakistan. Relatives to meet, weddings to attend, family business to take care of. Life has to go on..