Why is India seeking the help of the United States on Mumbai?

- Not only is the US the lone superpower, it’s also the country with the maximum influence over Pakistan

- New Delhi thinks that if the US is keen to avert an Indo-Pak conflict because of Afghanistan, Washington must persuade Islamabad to take substantive action against theperpetrators of Mumbai 26/11

- New Delhi broke the domestic consensus on foreign policy to embrace the US. It feels it’s now America’s turn to provide comfort to India in its moment of grief.

Can the US meet these expectations?

- Its problem is that it can push Pakistan only up to a point. Wouldn’t want to do anything that could compromise Pakistan’s support in the war on terror in Afghanistan.

- Therefore, it’s a tightrope walk for the US: avoid a Pak-India conflict, and yet enable the two countries to keep intact their national pride

***

Durrani’s admission was touted as the "first big step", but his resignation promptly dashed hopes of a coordinated effort between India and Pakistan in the ongoing investigation to nail the perpetrators of the Mumbai horror. However, the squabbles in Pakistan don’t have the Indian foreign ministry worried. As a senior official said, "It’s not a question of being optimistic or pessimistic. We have our job cut out, we will do what we need to do."

Part of this "job" includes mounting international pressure to isolate Pakistan unless it cooperates in nailing and nabbing the Mumbai perpetrators. This was why Union external affairs minister Pranab Mukherjee wrote to 184 of his counterparts worldwide, detailing Kasab’s confessions, the transcript of the conversation between the assailants and their Pakistani handlers and the details of other evidence such as the boat and GPS system the terrorists had used. In addition, the 131 heads of missions in Delhi were briefed about the ongoing investigations into the Mumbai attack and Pakistan’s role in it.

Some feel United States assistant secretary of state Richard Boucher’s presence in the subcontinent could have forced Pakistan to admit Kasab as its own. South Block officials, however, say it’s "too simplistic" to say Pakistan acted only because of Boucher. Before him, top US dignitaries—including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, John McCain and John Kerry—had been to Islamabad, mounting concerted efforts to have it cooperate with India. No less important was Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s recent statement accusing Pakistan of using terror as an instrument of foreign policy.

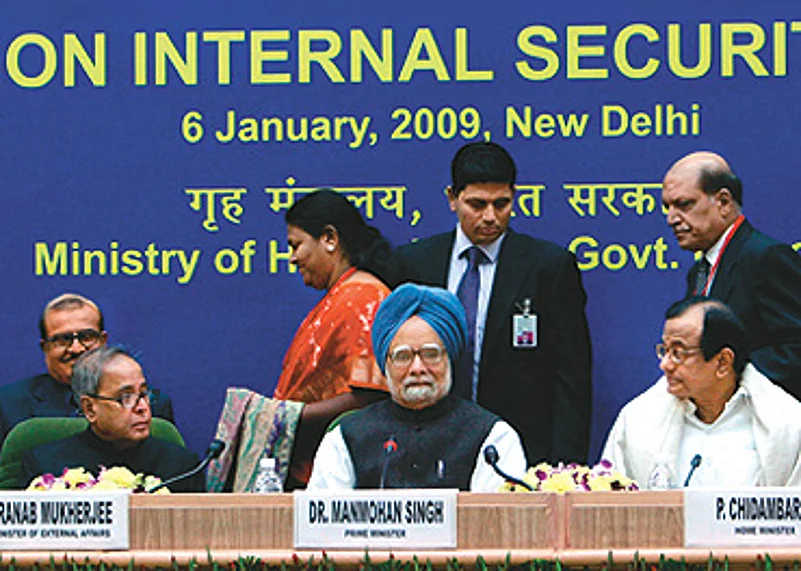

Talking tough: PM Manmohan Singh with his home minister and foreign minister

The Indian PM’s strong words had the international community, particularly the US, worried. Keen to avoid an Indo-Pak conflict lest it complicates their war in Afghanistan, the Americans thought Pakistan’s continued obduracy over the role of its citizens in Mumbai could compel New Delhi to take precipitous action to satisfy the public mood months before the general election. Adding to America’s fear was Mukherjee’s comment that war was not "exclusive, but inclusive" of all the options before India.

Mukherjee’s deliberate ambiguity about war is largely addressed to the US. Since Washington wants to avoid an Indo-Pak conflict, New Delhi expects it to mount pressure on Islamabad to act against terrorists operating from its soil. An Indian diplomat said, "There is expectation from the US, though it’s always difficult to quantify what we want." Obviously, the best-case scenario is to have Pakistan deliver the Mumbai masterminds—for instance, Lashkar operations chief Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi (see LeT it be Known: This isLakhvi)— to India. At the very least, officials feel, Pakistan must acquiesce to a point where the Congress and its allies can thump their chests to the polls.

Ironically, Delhi’s tough talk has raised public expectations about Pakistan’s acquiescence. These expectations have willy-nilly become linked to the belief that America would intercede on India’s behalf. Over the last eight years, the Indian leadership—both under the BJP and the Congress—has proffered every argument to justify its decision to inch closer to the US. The Congress even ignored the Left’s objections and imperiled its government to secure the Indo-US deal. The UPA consequently feels it is now America’s turn to return the favour by deploying its formidable clout over Pakistan and wielding the big stick to compel it to fall in line. Otherwise, the fears are that public support for India’s growing proximity to the US would shrink.

Former foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal told Outlook, "The government is expected to show some action on some front. That’s why the US role has become important." Ironically again, expectations from America have been raised because it surmounted all opposition to secure the Nuclear Suppliers Group waiver for India last year. Agrees Sibal, "Since the US played the cardinal role in riding over all opposition to see the nuclear deal through, it has fanned hopes in India."

But government officials are busy doing a reality check, wondering to what extent Indo-US relations can be milked. As a key prime ministerial aide argues, "Can we say that no such attack would have taken place if we had not entered into a strategic partnership with the US?" He says relations with the US have grown dramatically, pointing out that not only has its FBI furnished vital assistance in the Mumbai investigations, but also described the evidence India collected as "credible". However, though it has mounted pressure on Pakistan, he says, there are limits to what can be achieved through Washington. "It’s wrong to expect the US to pull out the Indian chestnuts from the fire," the prime ministerial aide said.

Agrees former foreign minister and BJP leader Yashwant Sinha, "The US will go up to a point in pressuring Pakistan, but not beyond it." He feels the US can at best help India bag a "consolation prize"—bans on a few terrorist groups and arrests of their leaders in Pakistan.

But then, America has its own compulsions. It doesn’t want to jeopardise its war in Afghanistan, particularly as Barack Obama is only a fortnight away from taking the reins from George W. Bush. Obama wants to pursue a "surge policy" of deploying more troops in Afghanistan to win its war against terror. Such a policy will only enhance Pakistan’s importance to the US. Says the prime ministerial aide, "The US will ratchet up pressure but not to the extent where the Pakistani turns against American interests in Afghanistan." Agrees former Indian ambassador to the US, Naresh Chandra, "The Obama presidency is unlikely to do anything that will jeopardise its surge policy."

Even as the Indian establishment assesses what America can provide, New Delhi is mulling over ways in which it can continue to mount pressure on Pakistan. Several steps have been suggested. Sinha feels the government should despatch leaders of different political parties to various world capitals to mobilise international opinion, as Indira Gandhi had done during the East Pakistan crisis of 1971. "It will clearly demonstrate that there is national consensus on demanding justice against the perpetrators of Mumbai," Sinha said.

Chandra thinks India should work closely with a number of countries, particularly China and those in the Gulf, to isolate Pakistan, and campaign vigorously in the US, particularly among the members of US Congress. Perhaps this could help stall the $14-billion package for Pakistan that the US Congress will take up in the coming weeks. Part of this package is for military assistance.

Should nothing substantial come out of these efforts, what can India do? For one, there’s a growing demand in the Congress for a response in the couple of months before the general elections. As such, New Delhi has a limited time-frame—till February-end before the election process unfolds. Many in the party endorse Sibal’s suggestion. He told Outlook, "We can call off the composite dialogue and the peace process," adding that India should soon start rolling back its diplomatic ties with Islamabad.

For, if the Congress fails to wrest major concessions from Pakistan, the Opposition is likely to launch a nationwide campaign against the UPA for its failure to deal effectively with the Mumbai crisis. This fear of the UPA’s has prompted New Delhi to believe that Pakistan, under Washington’s pressure, could hand over the Mumbai masterminds to the US, which had six of its citizens among the dead in the Mumbai carnage. Otherwise, officials feel, the UPA may opt for a harsher option to ensure that it isn’t seen as a weakling in the months before a fresh mandate is sought from the people. In may ways the growing shrillness of its pitch could well define the government’s goals and the paths it will take.