The western and eastern flanks merit different approaches. Traditionally, the Indian foreign policy establishment has tried to make a distinction between the challenges it faces from Pakistan and the ones posed by China.

Its western neighbour’s steadfast recalcitrance—the feelings are now mutual—has stemmed in part from its pathological hatred towards the idea of India, as manifested through direct or sponsored acts of terror in Jammu and Kashmir and elsewhere in India, most horrifically in the 26/11 Mumbai attacks.

Despite going to war with India in 1962 over the unresolved boundary, China has had a more pragmatic approach in its relations with New Delhi, where cooperation and competition have both been par for the course. Increasingly though, that distinction is getting blurred. Beijing has been stepping out repeatedly to shield Islamabad from initiatives taken by New Delhi to internationally marginalise Pakistan to force it to give up terror as its only foreign policy tool against India. It is significant, therefore, that the question is finally being asked: is Pakistan becoming a major impediment in improvement of Sino-Indian relations?

“Pakistan has always been an issue in India-China relations,” says C. Raja Mohan, director, Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore. “But now, it has become a lot sharper.”

It was the two-and-a-half-month military standoff between Indian soldiers and those of the People’s Liberation Army at Bhutan’s Doklam plateau that had hastened the informal summit between Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi in Wuhan in April last year. Nearly 18 months later, as the Chinese president is invited by the Indian prime minister to Mamallapuram for a second informal summit (likely to be held from October 11-13), the ‘Pakistan factor’ again looms large.

The most recent of these points of sharp divergence has been China’s making common cause with Pakistan at the UN Security Council against India’s decision to revoke Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir.

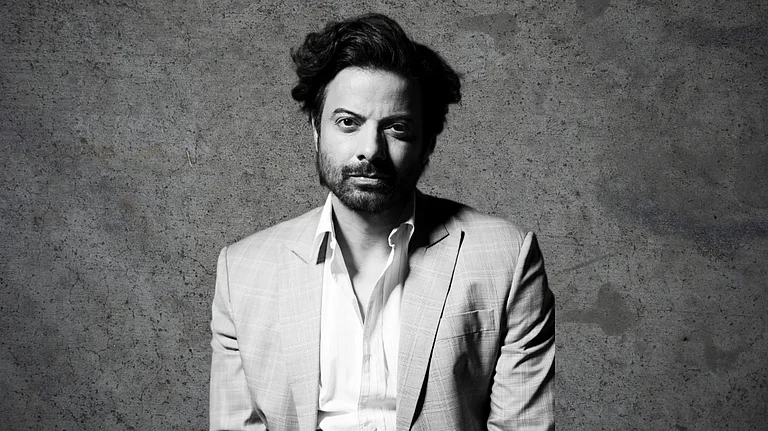

Modi and Xi at the 2017 BRICS summit in Xiamen.

“Actually, relations have acquired new wrinkles since Wuhan,” says former Indian foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal. He points out that China reacted sharply to constitutional changes in J&K. Despite Union external affairs minister S. Jaishankar’s explanations during his visit to Beijing that it had no implications for external boundaries, it did not ameliorate China’s hostility. It assisted Pakistan to place the Kashmir issue on the UNSC agenda after 50 years, then administered a double blow by making a public statement on behalf of the Security Council, contrary to normal practice. “It also had the temerity to speak of human rights violations by India. Though it has modified its position on J&K by alluding to UN resolutions,” adds Sibal. He points out their immediate fallouts: postponement of the next round of meetings of the special representatives on the boundary issue and that of the northern area commanders’ meeting scheduled in China.

China’s overt show of support for Islamabad was also seen early in March, on Pakistan’s National Day celebrations in Islamabad, when it flew past a squadron of its J-10 fighter jets. That it came soon after the potentially combustible Pul-wama/Balakot incidents was not missed by anyone.

Then there was the mulish stand on Masood Azhar. For years, China, by virtue of being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, had put a “technical hold” on the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed chief from being declared a ‘global terrorist’. It finally relented in May this year, agreeing to lift the hold on stamping Azhar as such.

China has also consistently prevented India’s membership in the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG), arguing that it has to be done in conjunction with Pakistan’s membership. It had similarly delayed India’s entry to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and agreed only after Islamabad too became a member.

“Pakistan remains a serious factor in India’s relations with China,” says Sibal. China, he feels, would have noted with concern the statements from Indian leaders on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir recently because of their implications for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). If a conflict occurs with Pakistan, the China factor immediately internationalises it.

“China is hitting at our weakest spot by supporting Pakistan; this cannot be overlooked by us,” adds Sibal. “It will remain an inhibiting factor in developing optimal ties, along with China’s territorial provocations.”

Sino-Pakistan relations have grown over the years—perhaps owing to the principle of close ties with “enemy’s enemy”. Ties started moving forward from the mid-1950s, when Pakistan dropped the Republic of China government in Taiwan in favour of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing. It soared to a higher plane after the Sino-Indian boundary war when, through a 1963 agreement, Pakistan conceded a sizeable chunk of territory in PoK to China.

In subsequent years, Pakistan has provided China a window to the Islamic world, as also allowing its territory to be used by the Chinese as a listening post to US activities in the region. It is also a major market for Chinese military hardware, accounting for nearly 47 per cent of all sales, and a major investment destination for China. The $60 billion CPEC is at the core of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, giving it overland access to the Indian Ocean.

Yet, despite its cosiness with Pakistan, China has been balanced in dealing with India-Pakistan bilateral issues on many occasions. As historian Srinath Raghavan argues, both during the 1965 and 1971 India-Pak wars, Chinese action backing Pakistan was limited to issuing demarches. It also kept a hands-off approach through the 1990s, even during the Kargil conflict after the nuclear tests of 1998. Indeed, this was a phase when the Chinese leadership asked Pakistan to keep aside the perennially contentious Kashmir issue and focus on areas like trade and economic cooperation to improve ties with India. There was, of course, a limit to China’s neutrality. In 2008, even when a Chinese national was among those killed by Pakistani terrorists during the Mumbai attack, China pointedly refused to join India and others in condemning Islamabad.

“China is concerned about terrorism but to the extent that it doesn’t reach its Muslim areas,” says Pakistani strategic commentator Ayesha Siddiqa. Pakistan is important to China, she says, because it’s a long, tested relationship. They have good defence-industrial ties and China has used Pakistan for decades to market its weapons elsewhere. “Besides, Pakistan acts as a good balancer vis-a-vis India,” Siddiqa adds.

Former national security advisor Shivshankar Menon, however, argues that China started leaning more towards Pakistan with the thickening of India-US ties. In his book Choices, Menon wrote that the US-India deal had “provoked a natural rebalancing (leading China to move closer to Pakistan) that we were probably slow to anticipate.”

Where does India stand in the face of its neighbours’ close embrace? Most experts feel that though the ‘P factor’ has negatively impacted Sino-Indian relations and forms the backdrop of the informal Xi-Modi summit, Modi and Xi will try not to allow it to affect ties beyond a point.

“In the last one year, we saw the attempt was to keep the border tranquil,” says Raja Mohan. There is a mutual awareness of the need for restraint and for a stable boundary, he adds. Raja Mohan feels that while the Chinese are concerned about where India is going with the US, India will be worried about Chinese activities in its neighbourhood. “There has to be trust. Even if differences cannot be resolved, there should be some understanding on what the other side is doing,” he says. “There has to be assurances that the red lines are not crossed.”

As Xi and Modi have a freewheeling discussion on these vexatious issues, their conversation will also focus on ways to strengthen the economic partnership between the two sides. In fact, the spiralling trade tensions between China and the US could afford opportunities for India and China to work for mutual benefit.

“Jobs have to be created, for which we need heavy investment from China,” says Alka Acharya, professor of JNU’s Institute of Chinese Studies. Though she feels India may not show its hand on allowing Huawei access for 5G technology in the country yet, progress is likely on other areas of trade access and investment.

She points out that Chinese investment in India’s infrastructure sector could employ large numbers of unskilled workers and may help ease some pressure on the government. Progress also beckons in other areas, like giving more access to Indian pharma firms for marketing cheap drugs in China—a huge domestic market—and revive other mutual commitments.

Cooperation between the regions of China and Indian states could also boost investment and trade. “Basically, it is fine-tuning existing hurdles and giving what had been agreed a push,” adds Acharya.

But the meeting between Xi and Modi takes place when global affairs are in a state of unusual flux, increasing unpredictability. One such is the Indo-Pacific area—one of immense importance to both China and India.

“The Indo-Pacific is a vast maritime space,” says C. Uday Bhaskar, director, Centre for Policy Studies. “Both India and China ought to evolve a politico-military framework where there can be a functional engagement and cooperation in a mutually acceptable manner,” he adds. This, he feels, could address the bandwith of safeguarding interests and assuaging anxieties.

But the biggest question continues to nag us: can they work together? According to Uday Bhaskar, this will depend on Modi and Xi’s perspicacity, strategic acumen and “the quality of advice given them by their principal advisors”. This apart, the two countries can work together for a stable West Asia.

“Both India and China have very high stakes in West Asian stability,” says Talmiz Ahmad, former Indian diplomat. Both countries, underlines Ahmad, depend on the region for oil and gas imports and have very significant economic interests. The region is India’s principal trade partner and source for investment. For China, besides trade ties, it is the locale of several multibillion-dollar projects that are being executed by Chinese companies. Besides, the region is extremely important to both countries for their connectivity projects.

“The region’s deteriorating security situation is thus a matter of great concern for both nations,” says Ahmad.

Modi and Xi had also been talking of working together in Afghanistan. But as India’s former ambassador to the country, Gautam Mukhopadhaya, points out, discussions will now have to be taken to the implementation stage by the two governments.

Realistically speaking, what will the two leaders bring to the table when they meet later this month? What, indeed, will be their take-away?

Maybe, an indication could be found in what foreign minister S. Jaishankar said recently during a conversation in the Council for Foreign Relations in the US. He admitted that there are differences between India and China on a number of issues—the boundary dispute, despite several rounds of negotiations, still remains unresolved. But the nations have also evolved a mechanism to address those differences. It has been a very stable, very mature relationship. Most important was his pithy comment: “Frankly, it is not a relationship that has given cause for anxiety to the world for many, many years.”

For all the tension involving our western neighbour, it is quite possible then, that in an increasingly unpredictable world, India-China ties will be a bulwark of stability.

***

Ayesha Siddiqa

Pakistani strategic writer

“China is concerned about terrorism only to the extent that it doesn’t reach its Muslim areas. It has allowed Pakistan to handle the Taliban. Pakistan-based terrorists don’t hurt China and have strategically stayed away from it. They do not threaten CPEC. But if the Iran-US war comes to the region and Pakistan is seen supporting the US, there may be problems.”

Talmiz Ahmed

Former Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia and UAE

“India and China enjoy high esteem and carry considerable diplomatic clout in West Asia. They can put in place a regional security arrangement. This will call for considerable effort and patience. India and China do have bilateral concerns, but they also have areas of convergence. West Asia is one such issue where their interests converge.”

Kanwal Sibal

Former foreign secretary of India

“China would have noted with concern the statements of our leaders on PoK because of its implications for CPEC. If a conflict occurs, even if limited, with Pakistan, China would help Pakistan internationalise it. China is hitting at our weakest spot by supporting Pakistan. It will remain an inhibiting factor in developing optimal ties.”

C. Uday Bhaskar

Director, Centre for Policy Studies

“India, along with many nations including US and Russia, have upheld the rule of law and customary practice in the maritime domain. The South China Sea dispute, involving nations with competing claims, is a sore point. But it would be misleading to infer that the whole gamut of India-China maritime cooperation is predicated on the S. China Sea.”

C. Raja Mohan

Director, South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore

“The Chinese would have concern on where India is going with the US. India will have concerns about China in its neighbourhood. They will have to be addressed carefully. There has to be trust. While differences can’t be resolved there should be understanding of what the other Is doing.”

Alka Acharya

Professor, Chinese Studies, JNU

“Huawei will be kept hanging in balance. Prime Minister Modi might try to see what else he can get from the Chinese President before he concedes. Huawei is also caught up in the world’s strategic debate. This obviously will be something that the Chinese will push for. Getting India in the kitty on this issue will be good for them.”

Gautam Mukhopadhaya

Former Indian ambassador to Afghanistan

“There is potential for parallel, even coordinated activities in investment in Afghanistan’s mineral sector and connectivity through Central Asia to Chabahar and also in countering extremism. But though there has been exploratory contacts at the track two level, China’s position remains too wedded to Pakistan to allow meaningful cooperation. China’s CPEC through PoK is another factor.”