When Louie Psihoyos’ documentary, The Game Changers released in 2018, it drew a volley of multi-faceted critique alongside roaring acclaim. The response was perhaps fit for a documentary that- through its academic research oriented underpinnings, as well as cinematic narrative weaving of some of the world’s highest performing athletes and their personal journeys of struggle and nutrition– sought to reorient the cultural narrative around the legitimacy of plant-based protein; and its viability in the space of athletics and body-building.

Nearly two years hence, the legitimacy of plant-based diets in spaces previously thought to be fulfilled exclusively through animal-based products still holds. Further, as a global pandemic rages on, this very viability now presents us with the only way to go onwards and upwards. Thus, on World Vegetarian Day, 2020, observed internationally on 1st October every year, it is time to not just acknowledge this fact, but also attempt to internalize and integrate it into our daily lives.

The origin of the COVID-19 crisis is by itself too, a by-product of unhygienic conditions in wet markets (fuelled in turn by a global demand for cheaply obtained meat). However, the fact is that meat consumption has been associated with disease long before the current crisis, and - if course correction doesn’t take place – will continue so long after the pandemic as well.

Over-consumption of meat is responsible for about 285 billion dollars spent annually worldwide on treating illnesses caused by red meat consumption alone. Worse still, the trade-off ratio of resource exhaustion to calories produced involved in meat-production is abysmal too-- the global livestock herd and the grain it consumes takes nearly 83% of global farmland, but produces just 18% of food calories and 37% of protein. It is also responsible for 60% of agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions; thereby greatly exacerbating the Global Warming crisis we find ourselves in.

Another important fact is that whilst eating meat can be on the surface level assumed to tie-in to national or ethnic food identity (think the cultural capital and imagery of American barbecuing, or North Indian butter chicken); vegetarian cuisine has not only just survived, but thrived too. Its endurance alongside animal-based products showcases not just a theoretical presence as an alternative, but a literal and pragmatic presence as a competitive alternative without the enormous environmental toll to boot.

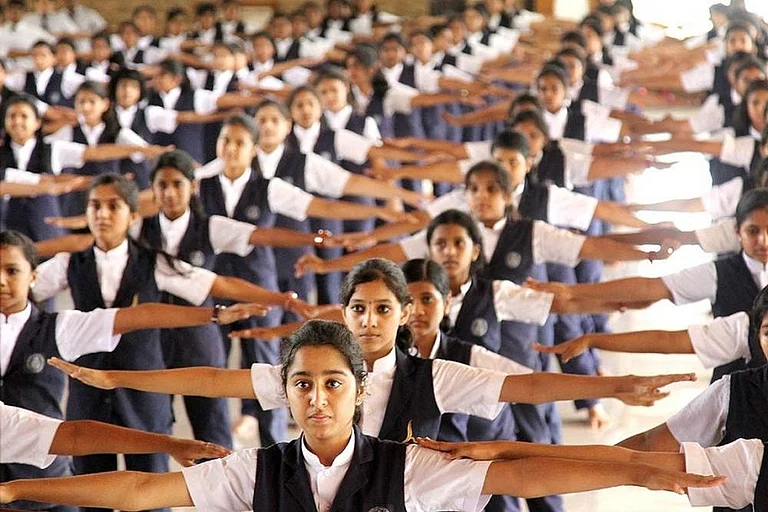

Cities with a diverse population and varied cultural leanings can generally be relied upon to even offer exclusive vegetarian eateries; and academic estimates suggest 20% to 40% of Indians being vegetarians (a figure muddied since most Indians do not consider people who eat eggs to be vegetarian, whilst globally the discourse and definition varies). The Indian diet, then, finds itself in a uniquely advantageous position to spearhead plant-based alternatives to traditional consumption. It is a vibrant diet that not only has a positive effect on the availability of plant-based options across the subcontinent, but a natural diet that is already poised towards plant-based products.

A commonly neglected fact– perhaps for self-moral alleviation, in part– is the mass, consumer-backed cruelty millions of animals are forced to go through on a daily basis in the meat industry. There is no circumventing or skirting around this aspect of meat production, to turn a blind eye to the violent and by all counts, inhumane slaughter is to do a disservice to not just one’s own intellect; but also the torturous life that went into the creation of the very food consumed without much of a lingering thought.

When it comes down to it, one cannot help but wonder why millions of animals are slaughtered when viable and cheap alternatives that are simultaneously healthy and nutritious, not just for the body, but also for the earth exist. Perhaps it is an internalized re-telling of one our favourite stories - that humans beings are the only sentient beings that matter and will ever matter. Or maybe we have told ourselves that meat-based products are part of some irreplaceable, collective human identity that we have co-opted from nature, despite strong evidence suggesting otherwise. Whatever we tell ourselves, when the generations yet to come turn to us and inquire of us– partially with curiosity and partially with contempt– as to why we failed billions of animals and the very earth itself, we will have no compelling answer; and nor have we ever had one.

(Views are personal. The author is the Executive Director of the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO), India’s apex animal protection organization.)