I knew I was swimming against the tide but I stood firm on my ground. My wife, Ranjita, visiting me at Sajiwa Central Jail, asked me what I had decided. I said I would never bow down, for I had done no wrong. It seemed everyone or everything was against me and my family. It is the truth that prevails in the end; and justice has been served. But the imminence of light doesn’t always feel like a guaranteed thing when you’re stuck in the tunnel. All hell had broken loose on November 19, 2018, when I criticised the ruling party and its government on social media for their lack of concern for the history, religion and culture of the region’s ethnic minorities. Yes, in my pique, I’d allowed myself some expletives…I realise I could have worded it in a better way. Anyway, I was arrested the next day, charged with sedition and defamation and remanded to six days’ police custody.

It seemed unreal—and luckily, temporary. On November 26, the CJM Imphal West granted me bail against the 15-day judicial remand sought by the authorities. My family breathed a sigh of relief, and I too felt the trauma slowly ebbing away. But the very next day, plainclothes police arrived at my house and picked me up—and I found myself sitting in the office of the Additional SP (Law and Order), Imphal West, for nearly five hours. I came to know I was being detained under the National Security Act (NSA) only after I was taken to Sajiwa.

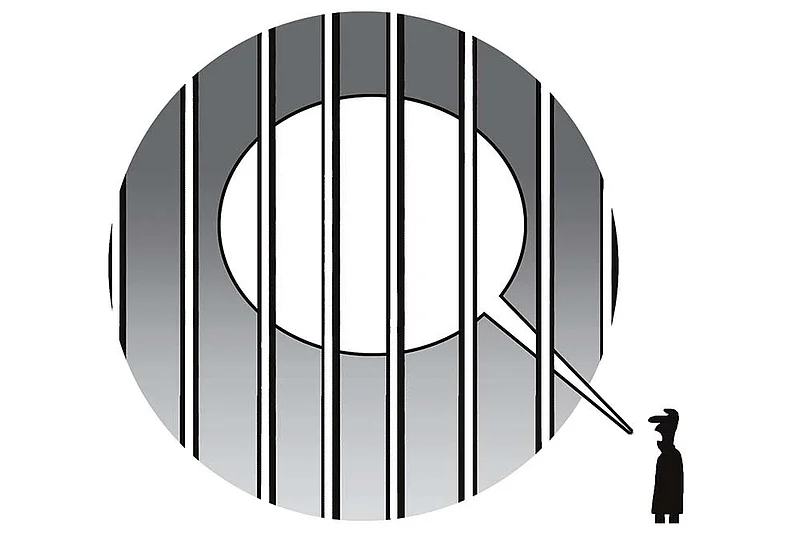

I belong to a small, unrecognised minority religion called Sanamahism, a pre-Hindu traditional ethnic stream. My point was not about the government’s other policies but the ruling party’s ideology: its recent attempts at religious and cultural assimilation targeting the smaller ethnic groups of the Northeast in general and Manipur in particular. Majoritarian rule has become a threat to the culture and tradition of ethnic minorities—the essence of their identity and being. Their very existence, in a way. My outburst also sprung from the suppression of dissent and abuse of right to freedom of speech and expression increasingly meted out to citizens in the last couple of years. Whosoever raises questions against the current regime is threatened, harassed or killed. As a concerned citizen, I felt I should speak up for the protection of minority identities. Popular outrage across the Northeast against the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which erupted a month after I was detained, was a manifestation of this latent anger among ethnic minority groups. What purpose does democracy serve if personal freedoms enshrined in the Constitution are not respected and secularism and plurality are challenged?