The state of Kerala, known for its highest wage rates in India, paradoxically exhibits the most significant gender wage disparity. Despite paying a minimum of Rs 800 per day to male construction workers, the state offers only half or less of this amount to their female counterparts in the same category of labour. This incongruity exists within a state boasting the highest social development index and the lowest poverty rate. According to a 2022 report from the National Statistics Department, Kerala exhibits the highest gender wage gap among large Indian states, both in rural and urban sectors.

In the rural region, the average daily wage for a male worker in Kerala is Rs 842, the highest in the country. In stark contrast, a female labourer receives only Rs 434, which, although the highest among large states, equates to a mere 51 per cent of a male worker's wage. It's worth noting that this phenomenon is not unique to Kerala; other high-wage states, namely Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, exhibit similar gender wage disparities despite being the top states in terms of male rural worker wages.

Contemporary Kerala society exemplifies striking gender paradoxes, particularly evident in low labour force participation and pronounced gender imbalances. The Economics and Statistics Department of Kerala has reported the state has the highest female unemployment rate in the entire country. As per the department's 2017/18 report, female job seekers constitute a substantial 63.2 per cent of the total workforce aspirants in the state. The recently published Kerala State Economic Review for 2022 further reveals the presence of significant gender wage inequality within Kerala. This disparity in wage rates is not confined solely to the informal or unorganised sector but extends to encompass regular or salaried employment as well.

“Though the wages of women engaged in casual labour in Kerala are higher when compared to the rest of the states, gender difference in wage gap is huge in Kerala,” says Sonia Goerge, the General Secretary of SEWA (Self Employed Women’s Association), the biggest women’s trade union in India. “A state which proudly presents its pro-labour stance with the highest minimum wage in the country, the gender discrimination in terms of wages is yet an issue to be tackled,” she said. According to Sonia George, who has raised critical concerns over the ‘gender budget’ in the State, the budget allocations are not showcasing any provisions to address this disparity. She says that while the participation of women in the formal sector is diminishing, the jobs that are created in the informal sector are mostly of an informal nature.

This gender gap in employment, as well as wages, is further widening over the last ten years due to the inflow of migrant workers to the states. According to experts, this has pushed Kerala women to be confined to informal sectors that demand unskilled labourers, such as hospitality, domestic work, textile industry, etc, in which women work with lower minimum wages. It has only worsened the situation as the government provides no systematic plans for sustainable livelihood development for women workers.

Gender difference in average wage/salary/earning per day from casual work:

Kerala is a deeply patriarchal society despite having impressive scales of sex ratio and higher education of women. In higher education institutions, girls occupy more than fifty per cent of seats, but when it comes to the labour market, the employment participation of women is lower than in many states such as Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh or Odisha. According to the Periodic Labour Survey of 2019/20, the WPR (Worker Population Ratio) of Kerala is only 27 per cent, a much lower figure compared to several other States that are far behind Kerala in terms of social development index.

The NFHS data highlights the paradox of this highly literate state in terms of women empowerment. Despite having a poor scale in terms of labour participation and wages, 92 per cent of women in Kerala have participated in key household decisions, and 79 per cent of women have bank savings accounts of their own. According to NFHS-5, 53 per cent of women in Kerala have money to decide how to use.

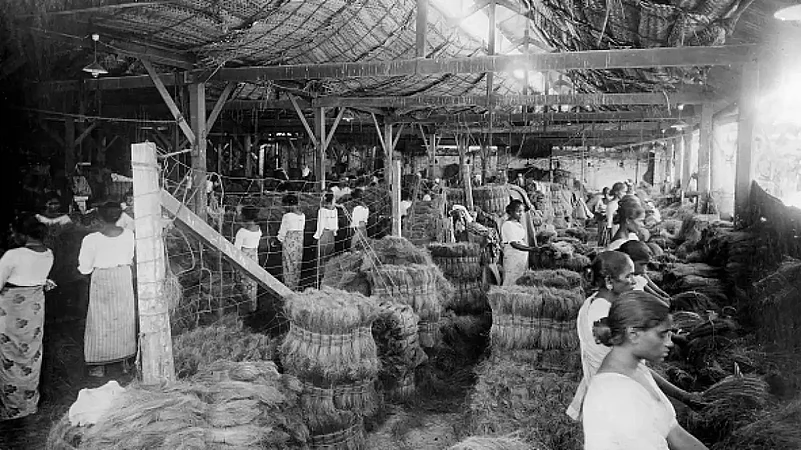

According to a study released by the Kerala State Planning Board, the gendered segregation of occupation has been used as a tool to justify the lower wages of women, which is illustrated in the payment for cashew workers and agricultural workers. The study underlines the fact that payment of unequal wages has been justified with instances of gendered segregation of occupations and also due to the consideration of women as supplementary earners.

Scholars contend that Kerala, characterised by its deeply entrenched conservatism and patriarchal norms, aligns with the principles of ‘human capital theory’ championed by the American economist Gary Becker. According to this theoretical framework, gender-based wage disparities result from variations in the skills, abilities, and knowledge that workers accumulate over time. As a consequence of differential socialisation processes that shape women's employment aspirations before they enter the labour market, women tend to invest less in the development of human capital. Consequently, women workers receive lower rewards relative to their male counterparts, not necessarily due to overt discrimination, but rather because, on average, they acquire comparatively fewer educational and skills resources, rendering them less productive than their male counterparts.

This theory has been widely critiqued, illustrating the upward mobility achieved by women in different standards of social development. However, the conservative notions about women’s employment are yet to change.

Significant disparities persist even 46 years following the enactment of the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976. This legislation imposes an obligation on employers to ensure 'equal remuneration for men and women performing the same work or work of a similar nature' within an establishment or employment setting. Commonly known as the 'Equal Wages for Equal Work' law, it not only addresses wage differentials but extends its purview to encompass inequities in recruitment processes, job training, promotions, and inter-organisational transfers. Additionally, the act endeavours to establish Advisory Committees at both the Central and State levels, aiming to foster employment opportunities for women and evaluate the effectiveness of the Act's implementation.

Kerala has no dearth of trade unions and welfare boards for employees. According to the Economic Review of 2022, there are 28 Labour Welfare Boards in the State (Labour Commissionerate). At present, there are 16 Welfare Fund Boards functioning under the Labour Department and providing welfare amenities to the respective sector of labour. The rest of the boards are functioning under various departments like Agriculture and Industry. The review proudly provides the data of workers registered under the Board. 64,74,501 people have been registered in 16 labour welfare boards under the labour department. Out of 16 boards, the Kerala building and other construction workers’ welfare boards have the highest number of members, i.e. 20,450,00 registered members. However, the Economic Review keeps a conspicuous silence over the number of female workers registered under the Boards.