As the Supreme Court hears a clutch of petitions on legalising same-sex marriages, Rakhi Bose speaks to lawyer Utkarsh Saxena, one of the litigants in court, about marriage, equality, and the ‘bouquet of rights’ that legalisation of same-sex marriages promises.

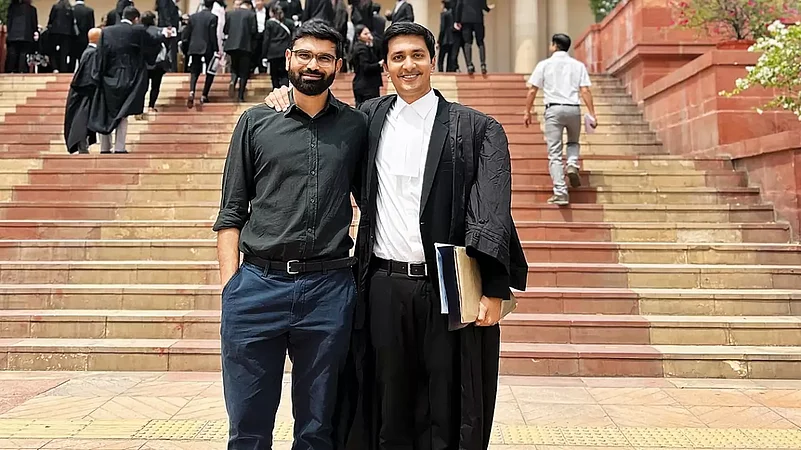

For senior lawyer and Harvard alumnus Utkarsh Saxena, growing up as a gay man in India wasn’t easy. Today, he represents the hopes of many from the queer community in the Supreme Court, which has been hearing a clutch of petitions aimed to legalise same-sex unions in India. Saxena and his partner, Ananya Kotia, filed a petition seeking legalisation in the apex court stating that as citizens of India, the two, who have been in a same-sex relationship since 2008, wished to marry. The historic hearings have become a flashpoint for several pertinent debates.

What does marriage mean to the LGBTQIA community and to you personally?

There are two reasons why marriage equality is important to us as a couple—one is at an emotional level and the other is in the socio-practical sphere. Most queer couples, at least in India, find it difficult to explain their relationships to the world. Marriage helps us define that relationship. The ability to marry allows us to become part of a familial social structure that everyone else is a part of. It makes us feel included. Those of us who have been lucky to find companionship want to give the relationship some structure and acceptance.

On the social front, marriage is a prerequisite for a range of rights that people take for granted but have been historically denied to queer communities. Whether it’s family-related rights, including adoption, surrogacy rights, or financial issues, lack of marriage equality becomes a hurdle.

Both my partner and I have been wanting to adopt for a long time. But the legal system in India does not recognise us as a married couple, a prerequisite for adoption. We can’t get joint bank accounts or file joint IT returns. We don’t have inheritance rights; we can’t be on each others’ health insurance. These are just a few examples of important rights that have been denied to the queer community.

Would you say marriage will translate into equality for the community?

In a legal sense, definitely. Right now, the choice to marry is unavailable and that in itself is important in terms of equality, to have the choice to be able to do anything without being hindered by gender or orientation. Right now, we are excluded from an important institution just by virtue of those two. That, to me, is discriminatory and exclusionary. Legalising same-sex marriage will be a step forward. The judgment will also be a step in the direction of social equality and inclusion and open up a range of questions about queer rights. Law and society are constantly playing a game of catch-up. Sometimes, society is ahead while at other times the law is ahead. In this case, the law is taking the lead. It’s still a long road ahead, but a favourable verdict will act as a catalyst to speed up the journey toward equality.

What about religious personal laws that govern marriage in India?

Personal laws are not up for discussion right now. It’s important to clarify this because those who are opposing same-sex legalisation at present are basing their narratives on how petitioners are coming after personal laws. That is incorrect. The ambit of the hearing concerns only the secular laws like the Special Marriage Act, and the Foreign Marriage Act.

But why?

There is a dominant argument that non-heteronormative unions are against Indian culture, faith and religion. Personal laws are probably a better repository for those arguments than secular laws. Despite progress in gender discourse, many conservative sections of society may at this point find any attempt to change the personal laws provocative or an attack on religion. It is therefore the usual practice, even in the experience of other nations that have legalised same-sex unions and other LGBTQIA legislations, to first go through secular institutions, such as a secular marriage or civil union before going into religious spaces. The whole purpose of secular laws like the Special Marriage Act is to accommodate those persons and marriages that are not accommodated in religion. That’s probably why the court segregated the two issues and wanted to do it in a piecemeal manner.

How does leaving personal law out of the purview of this litigation affect the queer community?

Without touching personal laws, we wanted to ensure that those who face opposition from families and aren’t coming from supportive environments, don’t face further legal restrictions to access the institution of marriage. That’s why our petition also focuses on the notice and objection regime.

These rules subject couples applying to marry under Special Marriage Act to intense scrutiny. Their photographs are put up on a notice board at a public office and 30 days are given to the public at large to come and object to the marriage. Those who come from non-supportive families will definitely face a hurdle.

In pursuit of true marriage equality, at least our petition contends that first the institution of marriage has to be opened up to all persons. Dismantling the legal architectures that create hurdles in accessing the institution of marriage will be the simultaneous step. As far as those who wish to be married under their faith, that battle is for another day.

What would this petition mean for the rest of the queer community?

Our petition seeks marriage equality for all sections of the LGBTQIA spectrum, including same-sex, transgender and intersex persons. If we are successful, we are hopeful that everybody in the queer community will be accommodated. Marriage equality is a massive step. Whether one wants to exercise their right to marry or not, there are many changes that are going to come if we are successful, that will help the entire community.

Lack of acceptance or acknowledgment of same-sex unions also ends up hurting a lot of straight people. For instance, queer people are often forced into heteronormative marriages, either because they cannot come out to their families or because their families don’t accept their orientation. These people are often forced to marry and have children. In a number of cases, by the time the queer persons realise they don’t want to be a part of it or get the agency to leave, it’s too late. They end up breaking marriages that affect not only them, but their partners, their children, and the families. It’s better for all if queer people are open about who they are so that they don’t get caught in the unfortunate social stigma that forces and coerces them to take decisions under pressure from families.

In India, marriage is a deeply caste-based institution and has often been seen as a propagator of caste system and patriarchy. How does the queer community intersect with the caste stratifications of India?

It might be true that marriage is a patriarchal and caste-based institution that promotes certain oppressive stratification and practices. However, marriage remains one of the most prevalent social institutions around relationships today. This is why the argument that it’s an urban and elite concept is incorrect because marriage is the most Indian social institution that exists and enjoys social sanction and legitimacy.

Second, no one is forcing queer couples to get married. All we are saying is that just like straight people, we should also have the choice to participate or renounce. Third, the idea that marriage is traditionally a patriarchal institution, and has been a vehicle to further certain oppressive pressures in society, does not apply to everyone who chooses to get married.

When two people get married in an interfaith or inter-caste situation, it would not be fair to say that they are furthering the problematic dimensions of marriage. In fact, in these scenarios, marriage challenges the very parochiality of the institution for which it is critiqued. Similarly, when a queer couple says they want to get married, it certainly opens up the institution more to progressive reforms.

These days, some straight people might find it “radical” to question the institution of marriage and not have children. But it often comes from a place of privilege because they have the choice to marry. So, for some queer people, the radical thing to do would be to participate in this institution of marriage that they have historically been denied.

(This appeared in the print as 'Personal Is Legal')