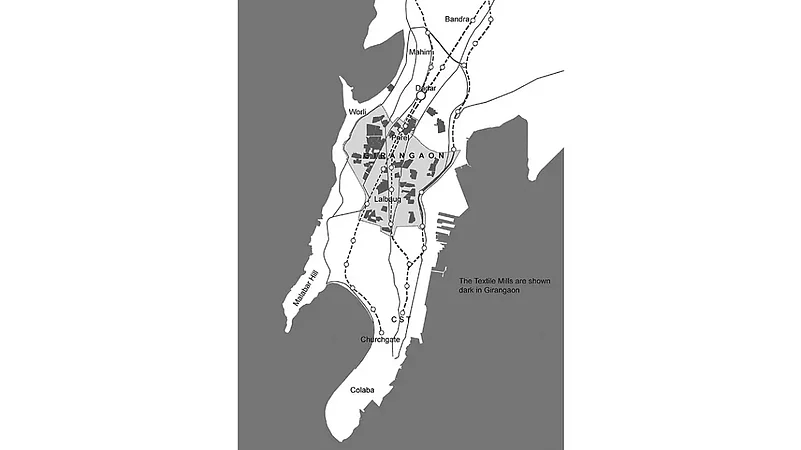

The Tulsi Pipe Road, now known as the Senapati Bapat Marg, was once lined with imposing facades of the Elphinstone Mills, Jupiter Mills, Mumbai Textile Mills, Phoenix Mills, Matulya Mills, Madhusudan Mills, Mafatlal Mills, Morarji Mills, Raghuvanshi Mills and many more. Today, these mills and their lands are in various stages of ‘development’. Some lie vacant after demolition, some are partly re-constructed. Many were redeveloped into swanky glass-and-chrome office buildings and gated multi-storey residential complexes.

A few yet-to-be-demolished mills are refurbished and house designer boutiques, art galleries, pubs and media offices. Iconic edifices of old residential chawls fringe the bazaar-lined streets of the area, which has evolved over a century and is connected to the suburbs by six railway stations. This neighbourhood has suffered class-based stigma developed and perpetuated by the South Mumbai elite and the growing suburban middle-class.

Demographic changes have shaved the stigma somewhat. It has also changed the area’s skyline and nomenclature. Crowds from Mumbai’s various middle-class localities have begun to commute here for work. But frustrated locals, who have named these opulently developed mill lands as the ‘Singapores of Girangaon’ feel disconnected in the current milieu. They demand to know their space in these ‘Singapores’.

From mills to malls

Modern mills, the birthplace of the Girni Kamgar Sangharsh Samiti (GKSS), has already been replaced by Belvedere Court, a 32-storey residential tower. The Phoenix Mills, now called ‘High Street Phoenix’ has a multiplex, and its Palladium mall caters to elite customers. Where there are now crowds of smartly-clad young men and women showing-off branded shopping bags, was the site of agitations against the first palpable signs of cultural gentrification in 1999.

The mill management had just closed the functional mill and converted its structures into a bowling alley and a spacious discothèque; the first cultural onslaught on the neighbourhood. The GKSS was the first to respond to this cultural rights’ issue by inviting artists, media-persons, filmmakers, singers and bards to stage a sit-in dharna on the pavement by the mill. It was the beginning of a new phase for GKSS, whose protest started the ‘Save Girangaon movement’, a new era of cultural confrontation.

The bowling alley and the disco were shut down for a month. This event caught the city’s attention and created a temporary fear about the newly emerging entertainment and leisure industry. Subsequently, mill land contestation became part of the conversation about Mumbai’s urban policies in the context of workers’ rights.

Growth, failure, identity

Between 1840 and 1880, as Bombay grew, there were 70 operational mills in central Mumbai. Two-thirds of the city’s labour in the 1930s were textile mill workers. An estimated 80 per cent of the workers lived within 15 minutes from their place of work, creating a culturally rich neighbourhood. Until 1982, when the decline of the textile industry started, there were 250,000 workers employed in 60 mills in the city’s heart.

Girangaon was the site for many political movements and cultural clashes, through which mill workers developed a sharp political consciousness over a century. The failure of the historic 1982 strike led to the decline of the Left-led trade unions, and the subsequent mill closures led to unemployment. A few mill workers, mostly aligned to the Left, formed an informal committee, the ‘Band Girni Kamgar Samiti’ (Closed Mill Workers’ Committee) to revive some mills. After tasting some success, the committee converted itself into a formal union, the GKSS. Unlike other city trade unions, which were led by middle-class ideologues, GKSS was led by the workers themselves.

The red tape

The introduction of modified Development Control Regulations (DCR) 58 in 1991 by the state government for the first time had permitted owners to sell a portion of mill lands. They could either modernise their mills or share two-thirds of the mill land for equal division into areas for public housing and open spaces. GKSS, however, suggested an alternative, which staked claim to a share of the land for workers’ housing and alternative employment.

Meanwhile, mill owners stalled the process and built a nexus with real estate developers, bureaucrats and politicians to further modify the DCR 58, which would leave them with a larger land share.

The 1990s new economic policy had facilitated conversion of industrial land into commercial or residential areas, leading to Mumbai’s large-scale de-industrialisation. Since 1991, nearly four million sq mts of industrial land has been converted into residential and commercial zones in the suburbs, amid the real estate boom. Parallelly, working-class sector job losses clocked more than one million, indicating a shift in the status of the workers, from formal to informal labour.

The initial development plan of 1885 mandated textile mill land to be reserved for the purpose of textile mills alone. In 1991, the government (through DCR 58), allowed for development of mill land, limited to revival and modernisation. However, if the mill owner opted for total mill closure under the same DCR, 33 per cent of the mill land was to be handed over to the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) for public open spaces and another 33 per cent to the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) for public housing. The rest was to be used by the mill owners. There were other incentives too.

All calculations of land area were to be made on the basis of the entire plot rendered vacant after demolishing the existing mill structures. By this tripartite formula, out of the total 600 acres of mill land area, the city stood to gain about 200 acres, both for public open spaces and for affordable public housing.

In 1996, the government appointed a committee under well-known architect and planner Charles Correa to draft a comprehensive plan for all closely clustered mill lands. The committee, however, did not consult the GKSS, which represented the mill worker constituency.

Twist in the red tape

As the financial globalisation era influenced Mumbai’s spatial restructuring process, the urban development ministry appeared shaky over the mill land sharing issue.

Even as GKSS and mill owners/developers continued their negotiations with the government, in March 2001, came the most debatable modification to DCR 58. This alteration drastically reduced open mill land to one-fourth of its entitlement towards public housing and open spaces. The implications were shocking not only to the mill workers but also to the city. Less availability of land meant less area for housing of former mill workers and their families as well as fewer space for public utilities.

Unite to fight

Mumbai’s citizen dissent space has also seen staggered changes over time. ‘Upper category’ citizens’ groups, which represent the ‘sanitary’ concerns of the middle classes, raise issues related to beautification and cleanliness based on 19th century colonial beliefs that poor localities threaten the city’s health. Their primary agenda is to reclaim public spaces from ‘illegal encroachers’ like slums, hawkers, etc. Such groups, known as advance locality management (ALM), abetted by civic authorities, have mushroomed and are a strong visible force against slums and hawkers in middle class neighbourhoods.

On the ‘other’ side of the spectrum are NGOs and people’s movements representing the slums, hawkers, and other marginalised sections. But there is a third category which is not disabled by globalisation materially and is ideologically and politically opposed to globalisation/neo-liberalisation. These are middle class social/political activists, individuals or organisations with a broad liberal left ideology, working on issues related to human rights, gender, secularism, peace and public health etc., and support grassroot struggle-based organisations from the outside and as an interface.

In such a diverse gamut of the civil society, the GKSS proposed a collaborative intervention, by initiating a common forum called the Mumbai Peoples’ Action Committee (MPAC). Like a ‘rainbow’ coalition, it put together a platform for battling the mill land issue in courts and through the media, hoping to generate a common minimum intervention in Mumbai’s socio-spatial and economic issues. The MPAC through intense interactions has managed to bridge rigid stances among the varied civic groups by understanding each other better. For example, mill workers too have included the need for public city open spaces within their housing agenda.

Epilogue

Today, Mumbai is at a critical juncture. On the one hand, the State and free market forces are aggressively projecting an ‘all well’ image, by presenting a brave front in spite of the global recession. On the other hand, cracks in such postures are emerging. For example, the most prestigious and ambitious project of redeveloping 400 acres of Dharavi’s slums is stalled by global bidders.

While a big developer has pompously announced the construction of the world’s tallest residential building at the Apollo mills’ site, mill workers are proudly looking forward to allotment for all the existing people who are buying at the cost price from MHADA. The 7,000 that were already allotted don’t represent even 10 per cent of the total housing units for mill workers that were also bought at the cost price but the struggle continues for the remaining existing mill workers.

Some would like to call this a result of the ‘welfare’ policy of the government extended towards ‘political society’. I would argue that this is an achievement by ‘insurgent citizenship’ after a head-on struggle based on a paradigm shift.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Get Up, Stand Up")

(Views expressed are personal)

Neera Adarkar is a Mumbai-based architect and urbanist. She has three books to her credit