January should be the month of collective atonement, repentance and cleansing for all Indians. January, after all, to use a Gandhian metaphor, has been made sacred by the blood of a man who was once called and accepted as the father of the nation. On January 30, 1948, barely five months into independence, it was decided that the nascent nation had seen enough of Gandhi. The time had come for India to detach itself from him.

Read Also

- Happy R-Day! by Rajesh Ramachandran

- Patriotism Vs Jingoism by Ramachandra Guha

- A Nation Within 4 Temples by S. Gurumurthy

- From Amir Khusrau To Filthy Abuse by Irfan Habib

- Don’t Foist Fear Onto Nationalism by C.K. Saji Narayanan

- Rockbed Of Cultural Renascence by Dr R. Balashankar

- Gandhi Smriti Diary by Brij Pal and Vishnu Prasad

January 30, 2018 marks the completion of the 70th year since the assassination of Gandhi. Why is a nation that is so fond of anniversaries, and which is recovering from the celebrations of the 70th year of independence, so indifferent to this particular anniversary? There is a lot of hullabaloo over the 150th year since Gandhi’s birth. The government has promised to celebrate it in style and on a grand scale. But why is it that we just want to pass by the anniversary of his killing?

Is not his death the searchlight which illumines the meaning of his life? Why not proceed backwards from this point to understand and grasp the significance of the man? A man who was more “womanly”, had deliberately shed manliness and asked his people to cure themselves of this disease.

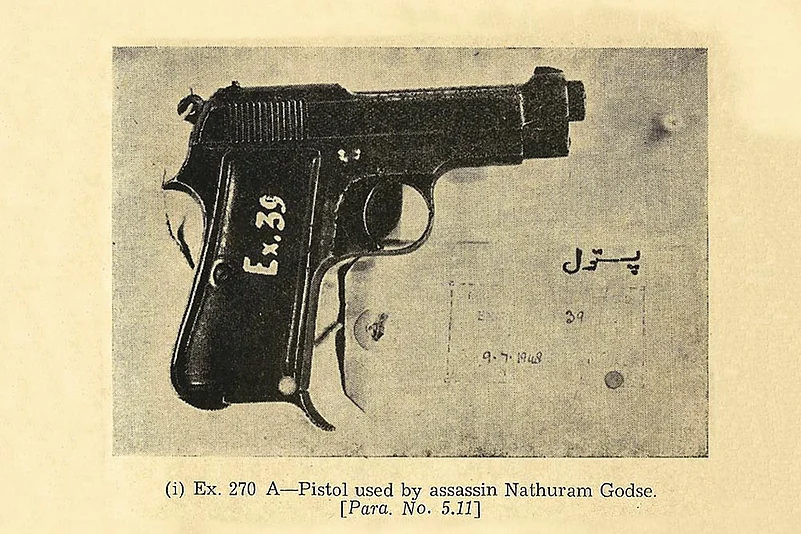

Godse (centre) with Savarkar and the conspirators

Is it wrong to say that Gandhi was consciously walking towards his death? He, the true friend of Gurudev, was not afraid, for death was his friend. One must remember that January 30 was not the only day he was attacked. He had encountered physical violence in South Africa. In India, he received letters threatening murder, and survived at least five attempts which could have been fatal. In one attempt at Sevagram in 1944, the man who would ultimately be his killer was involved. We know that January 20 could have been his last day when a bomb was thrown at his prayer meeting.

When he received messages praising his courage after that bomb attack, he said that his mere survival could not be proof of bravery. He could be called brave only when he knew that he was facing death and would not cower before it. Courage consists not in taking another’s life but in the readiness to lay down your own for the cause you believe in. When the appointed hour comes, do you waver and drag your steps back, seeking mercy, or face death with a smile on your lips?

So, was Nathuram Godse a lone wolf? Was he was acting on behalf of many among the people who wanted Gandhi out of the life of independent India? Gandhi’s presence was putting unnecessary pressure on the government of free India to be soft with Pakistan. Not only that, he insisted on making India safe for Muslims, which could not be permitted. And we are mistaken to think that it was only his pro-Muslim stand which earned him the wrath of a section of Hindus. You do not have to be Hélène Cixous to realise that there was hatred against him for being on the side of the people “from the gutter”, those who are called scheduled caste.

A secret memo filed by Kartar Singh, a CID inspector who cites a source identified as SEWAK, reports the proceedings of a meeting held on December 8, 1947 at the camp of the RSS on Rohtak Road. According to the memo, lying in the archives of the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, M.S. Golwalkar addressed the meeting, which was attended by 2,500 people. The report further says, “Referring to Muslims, he said that no power on earth could keep them in Hindustan. They shall have to quit this country. Mahatma Gandhi wanted to keep the Muslims in India so that the Congress may profit by their votes at the time of election. But by that time not a single Muslim will be left in India. If they were made to stay here, the responsibility would be the Government’s, and the Hindu community will not be responsible.”

“Mahatma Gandhi could not mislead them any longer. We have the means whereby such men can be immediately silenced, but it is our tradition not to be inimical to Hindus. If we are compelled, we will have to resort to that course also.”

Gandhi was in Delhi when this intent was being articulated internally. However, the capital had not been part of his original itinerary. He had been moving for months across states with a handful of colleagues, trying to douse the communal violence that had engulfed India. “I am in a fire-pit”, he says again and again. He was certainly aware of the hatred against him in the majority community, and wondered in letters and conversations whether he would come out of the ordeal alive.

Those who condemn him for being pro-Muslim forget that he had spent months in Noakhali, now in Bangladesh, a Muslim-dominated area, from where news of the killing of Hindus had reached him. He camped there consoling the Hindus and telling the Muslims that they had no right to attack or drive away their neighbours. When he was needed in Calcutta and Bihar and had to leave, he left his most trusted colleagues behind in Noakhali to carry on the mission. Violence was in the air and they could fall prey to it. But that risk had to be taken.

Gandhi kept an eye on the news emanating from Pakistan. Referring to the persecution of Hindus and Sikhs in the new nation, he asked the latter’s leaders to keep their word again and again. Had not Jinnah assured the Hindus and Sikhs that they would enjoy equal citizenship rights in Pakistan? So, what was happening now?

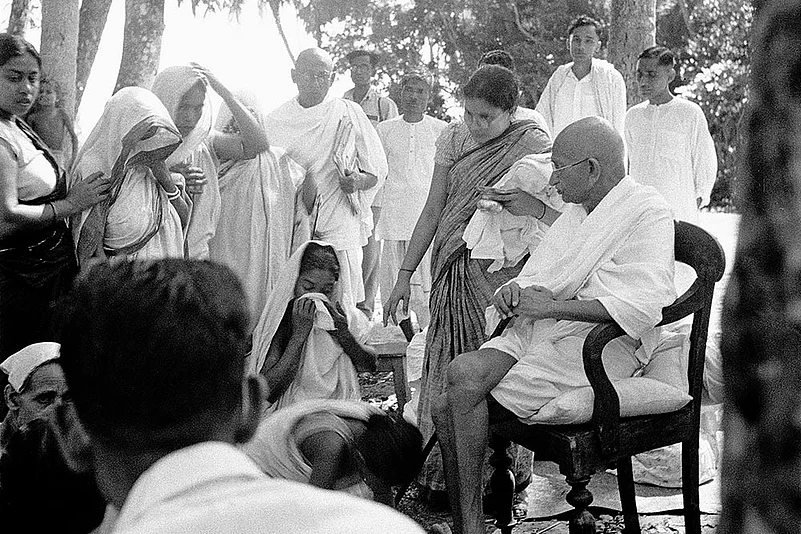

Gandhi consoles women in Noakhali, November 1946

Gandhi was mocked and asked why he was not going to Pakistan to save Hindus and Sikhs. He intended to do just that. After bringing calm to Calcutta and Bengal, he planned to move on to West Pakistan. He wanted to ensure that the Hindus and Sikhs who had fled thence could return and live in their old neighbourhoods. Similarly, he wanted to bring back with him the Muslims who had been forced to leave India. It was an audacious plan. But Gandhi dreamt impossible dreams.

However, the violence in Delhi convinced him that he had to go there and test himself once more. He repeated his slogan “do or die” while referring to his task in the new situation. With what face would he go to Pakistan? When Muslims were not safe in the capital of India, how could he ask the leaders of Pakistan to make their country safe for Hindus and Sikhs? Seeing Muslims attacked, he made up his mind immediately: his place was to be Delhi.

Gandhi had been called to Delhi by Nehru and Patel earlier, seeking his advice on important national matters. He had then refused to return from the burning fields of Bengal. He was more a man of action and was not sure if he had ideas that could help them.

But now the capital city had become a place where he could make a difference, for it had become a perfect arena of action, and he decided to plunge himself into it fully. Gandhi was not a flying Mahatma; he always believed in dealing with things hands-on. It was not for others to put into practice his ideal of non-violence; he had to do it himself.

In Delhi, Gandhi faced grief, anger and hatred, emotions very familiar to him. He now faced his own people—he had been their voice until only a few days before, but now he had to speak against them. He was well trained in the art of argumentation; not only the imperial power of Britain but all the West had bowed before him. But would independent Indians listen?

He received many displaced people of all creeds. Moving from camp to camp, he listened to tales of human savagery. He empathised with the Hindus and Sikhs but refused to let them inflict revenge on innocent Muslims in Delhi and India. Violence never cures violence.

Gandhi was not heeded. Violence kept returning to Delhi; his people had turned against him. He, however, could not treat them as incurable. Was his much-celebrated non-violence a farce? It could not be. There must be some weakness in the instrument that he himself was. Therefore, the instrument had to be tested and perfected.

Gandhi, who was approaching 80, went on an indefinite fast. It would end only when he was convinced that Hindus and Sikhs would invite Muslims to be their neighbours without any coercion. Would he survive this ordeal? He persisted in his demand until it bore fruit on January 18, when leaders of all communities approached him with a declaration that they would ensure peace and togetherness in Delhi.

Breaking his fast, Gandhi warned them that they would be held responsible for any recurrence of violence in Delhi or any other part of India.

January 2018 is the 70th year of the pledge to Gandhi. The time has come to redeem that pledge and to be true to him, which means nothing more than being true to ourselves.

***

Nathuram Godse made his first attempt on Gandhi’s life at Panchgani near Pune in 1944. He was the leader of a group of anti-Gandhi protestors who arrived by chartered bus. They shouted slogans all day, and Godse refused Gandhi’s invitation to debate. At the prayer meeting that evening, Godse rushed at Gandhi with a knife but was stopped. Gandhi asked Godse to stay a while so that he could understand the latter’s point of view, and allowed him to go when he refused.

Apoorvanand, the author is a professor of Hindi at the University of Delhi