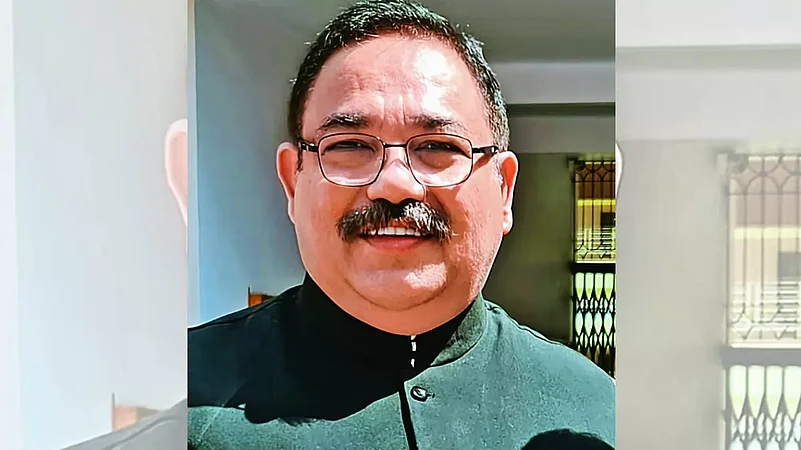

In 2019, through the 104th constitutional amendment, the central government discontinued the nomination of Anglo-Indians to the Lok sabha and several state assemblies. When the current Jharkhand state assembly dissolves in 2024, Glen Joseph Galstaun shall be the last nominated Anglo-Indian MLA in the country. In an interview with Abhik Bhattacharya, Galstaun discusses the absurdity of the 2011 census that found only 296 Anglo-Indian members left in India which was cited as the reason for discontinuing the political reservation for the community. Edited excerpts:

Could you elaborate on your Anglo-Indian heritage?

My great grandparents on the paternal side were Irish whereas my great grandfather on the maternal side was French. Coincidentally, my paternal ancestors settled at Arrah in Bihar and my mother’s family settled in Buxar, also in Bihar. We have been staying here for centuries. In 2000, prior to the bifurcation of the state, my father was nominated by the then chief minister Nitish Kumar as an Anglo-Indian MLA in the state. However, with the bifurcation, the seat was moved to Jharkhand and he became Bihar’s last nominated Anglo-Indian MLA and Jharkhand’s first.

What is the current distribution of Anglo-Indians in Jharkhand?

The members of the Anglo-Indian community are basically urban habitants and are scattered in every nook and corner of India. The same applies to Jharkhand and one can find them in Ranchi, McCluskieganj, Dhanbad, Ghatshila, Gomoh, Chakradharpur, Gumla, Bokaro, Hazaribagh, Koderma etc with Jamshedpur having a large Anglo-Indian population.

Do you have any memory of, or a connection with McCluskieganj?

I personally don’t as I stayed mostly in Ranchi. But we had our bungalow in McCluskieganj. When Jharkhand was formed and Naxalite threats grew over time, our father donated it to a police station.

Could you elaborate on the history and the political status of the Anglo-Indian community?

The history of Anglo-Indians goes back to the time when Europeans settled in India. The British started the railways, the post and the telegraph, set up customs, and naval and air forces. Because all of these needed specialised people for operational purposes, they brought in people from across Europe who were called ‘covenanted hands’. But the European womenfolk were left behind. So, some of the foreigners who were in charge of all these strategic operations got married to what they called ‘native’ women. Their offspring were called Eurasians, and later on, ‘Anglo-Indians.’

Primarily, they were looked down upon by the British due to their skin colour and descent. However, with the passage of time, they understood that it was a skilled and competent workforce. The railway services along with several other departments were totally dependent on them. It was only from the 1830s that the British started recognising them. Even in the mutiny of 1857, there was an Anglo-Indian regiment that supported the British.

Soon, the community realised that it was not given a fair deal and started voicing its concerns. Anglo-Indians could neither go back to Europe due to prejudice against them nor could they find the space they deserved in India. The term ‘Anglo-Indian’ was used for the first time in the Government of India Act, dated 2 August 1935, which formally recognized Anglo-Indians as a minority community. So, every year, since 2001, we have been celebrating ‘World Anglo-Indian Day’ on August 2.

How did Anglo-Indians achieve political reservation for being nominated to the parliament and lower assemblies?

After Independance, while communities such as Punjabis and Bengalis got their own state, Anglo-Indians were spread across the country. So, Ambedkar and Nehru were contemplating giving us a separate state. Responding to this offer, Frank Anthony clearly said that we were against partition and we would not accept any such measure where we would be given a separate state. It is said that Mahatma Gandhi—who was impressed with the way in which the Anglo-Indian regiment restored peace after the mutiny in Punjab—thought that this population of around 3-4 lakhs people who had contributed to the independence movement in a big way, must be recognised. I think it was his idea to give nominations to us in the lower house of the parliament and the state assemblies.

I think we got the nominations in return for what our leaders did for the country. At the Olympics, Anglo-Indians won gold for the country! The railways, post, telegraph and custom departments, in all of which we had some reservation, were run by us. However, in the early-1970s, the reservation was discontinued. We didn’t fight for it as we didn’t want to be spoon-fed. There were many Anglo-Indians who, after Independence shifted to England as they considered it their homeland. But there were also many who stayed and navigated their ways through several crises.

But, according to the 2011 census, there are only 296 Anglo-Indians across the country...

During Independence, our population was around 3-4 lakhs. Do you think that the population got reduced in such a drastic manner? Our Association has 66 branches across the country. In 2019, we met the then law minister and asked him how they arrived at that number when there was no specific column for declaring Anglo-Indians status. Their data shows no presence of Anglo-Indians in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Jharkhand. Then, how do they have nominated Anglo-Indian MLAs in these states? From Kerala alone, one of our branch presidents submitted 10,000 signatures compiled in a book form with Aadhaar cards to the law minister! This number is just not right! I’m guessing that people put in ‘Anglo-Indian’ in the ‘Religion’ column which could explain the number. They could have contacted us at the All India Anglo-Indian Association, the oldest organisation representing the community instead of taking a one-sided decision.

In 2009, the reservation was extended for another 10 years along with that for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes but in 2019, we were left out.

Would you say the community still needs political reservation in the form of nominations?

As a minority community, we deserve the right to be represented. It is a matter of social justice. There are several people from our community who still suffer due to socio-economic, political and other issues, struggling to find ways and means to acquire higher education and a roof above their head. Moreover, the Anglo-Indian community does not belong to or reside in any particular region or state; they are scattered across the length and breadth of the country and thus it is very difficult for us to win elections. So, nominations are the only way our voices can be heard. We’re Indians and our voices must be heard. It is our right given to us by our constitution. Natural, social and political justice should prevail.

In your three terms as MLA, in what ways have you worked for the benefit of the Anglo-Indians?

Matters related to the Anglo-Indian community have always been my priority on the political front. They say, “If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day; if you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.” Keeping this in mind, it has been my endeavour to ensure that the youth got quality education, at least up to the senior secondary level. Hence, free education along with boarding and lodging has been made available and scores of Anglo-Indian children from Jharkhand and Bihar are beneficiaries. Many children will be given education for the next 8 to 10 years. Moreover, unemployed people are being provided a decent package to live a secured life.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Game Of Numbers")