Delhi’s pollution is so bad, it’s visible from space—an acrid band of haze stretching out, west to east. The capital’s air-quality indices make even Beijing’s look healthier. After much public stink, a customised plan to scrub out pollution is on the verge of being made public by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. The ministry will then seek expert comments on it, as is the rule, before notifying it under the flagship Environment Protection Act. There are quibbles already about how far it should go. Yet, even a feeble response to pollution is better than none at all in a city of 25 million, where the dreaded smog descends typically during winters, stoking an inescapable horror in which the eyes sting and the lungs gasp. When the haze clears and schools reopen, the problem is mostly forgotten.

The Delhi government, with limited powers compared to other states, has swung from one stop-gap measure to another over the past year. When it first brought in a traffic-rationing scheme in January 2016, based on a simple formula (odd- and even-numbered private vehicles were told to stay off the road on alternate days), the city saw a significant dip in emissions. It was discontinued, with the government saying it cannot be made permanent until 3,000-odd new buses joined the public transport fleet and more bus corridors were laid. The government then moved on to fancier stuff, such as announcing air purifiers would be installed at major traffic intersections. According to Sarath Guttikunda of Urban Emissions, an expert group, that’s nothing more than hog wash.

As winter crept in this year, odd-even didn’t return. Moreover, although the state environment department deployed some standard measures—ban on trash burning, for instance, along with an official warning issued on November 4 that horticulture and sanitary inspectors would be made “personally responsible” for violations, or the ban on operating power generators that run on fossil fuels placed by the Delhi Pollution Control Board (DPCB) under the Air Act—enforceability remains a problem.

“Nearly 60 per cent of the polluting sources are outside Delhi’s territorial limits, so we cannot control them,” says a state environment department official. It was a “major global embarrassment”, says another official, when the WHO’s 2014 Urban Ambient Air Pollution database proved Delhi is the world’s most polluted city. As per the WHO’s 2016 update, things have improved only slightly, with very few days in a year when Delhi’s air doesn’t correspond to a “poor” or “unhealthy” rating.

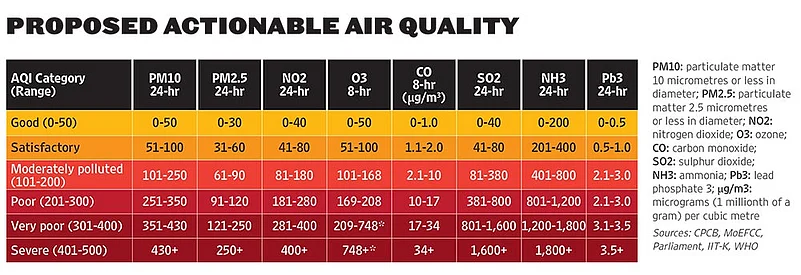

With a legally enforceable plan now in the offing, the authorities hope to mount a “Beijing-style” step-wise response. “It will apply not just to Delhi, but all NCR states (Rajasthan, Haryana and UP),” says Prashant Gargav, a Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) official. The plan will spell out a series of mandatory steps that the authorities need to take whenever pollution levels exceed acceptable levels. Given that Delhi perennially has poor quality air, some steps will be permanently in force. Progressively, the steps get more stringent as pollution goes up. Such step-up plans are popular across global cities. Sao Paolo has one, as do Beijing, Paris and Los Angeles. Prescribed air-quality standards are yet to be finalised.

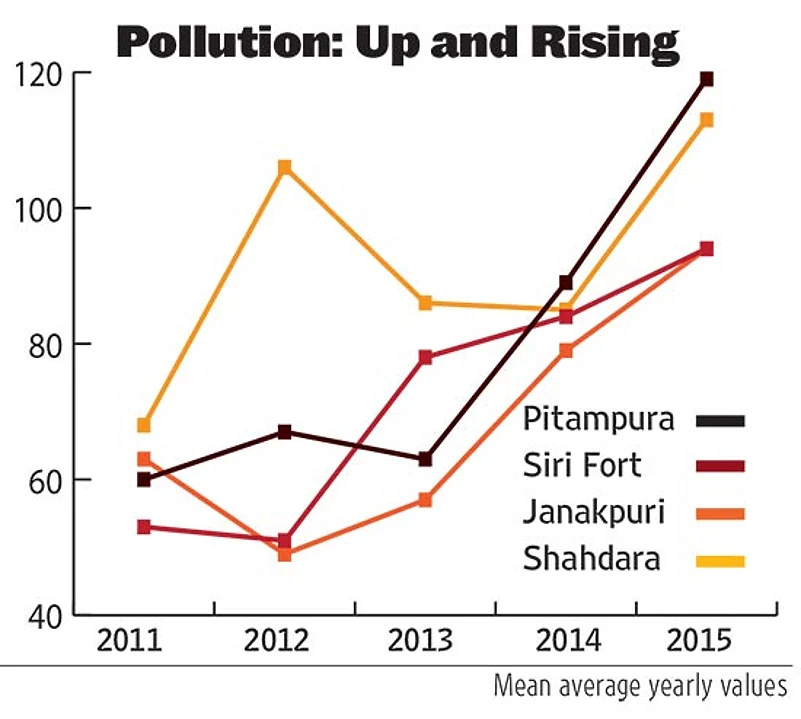

The deadliest aspect of Delhi’s pollution are the levels of PM2.5—dust-like matters so small they lodge deep into the alveoli (oxygen sacs in the lungs)—that shoot up dangerously sometimes. Between November 7 and 10, it went several dozen times over the limit at many places in the city.

Yearly averages of PM2.5, which provide estimates of continuous exposure, present a shocking picture. According to WHO guidelines, the annual mean limit of PM2.5 should be no more than 10 micrograms per cubic metre. Delhi’s annual mean touches 122—a staggering 1,100 per cent more.

Indeed, pollution is killing Delhites silently, whether or not there’s smog. “People basically become perennial passive smokers. Imagine making a non-smoker smoke a full packet of cigarettes a day,” says Dr Sushil Sharma, chairman of the Arthritis Foundation of India. He recently operated a patient who suffered complications only because of her poor lungs.

Health warnings have been coming intermittently, but policymakers just had no way to respond. Back in 2010, a study by Calcutta’s Chittaranjan National Cancer Institute found that a little less than half of Delhi’s children had diminished lung capacities of the sort normally associated with regular smokers.

New research shows that more than 5.5 million people die prematurely every year worldwide due to air pollution. “More than half of the deaths occur in two of the world’s fastest growing economies, China and India,” says Michael Brauer of the School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia. These findings were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

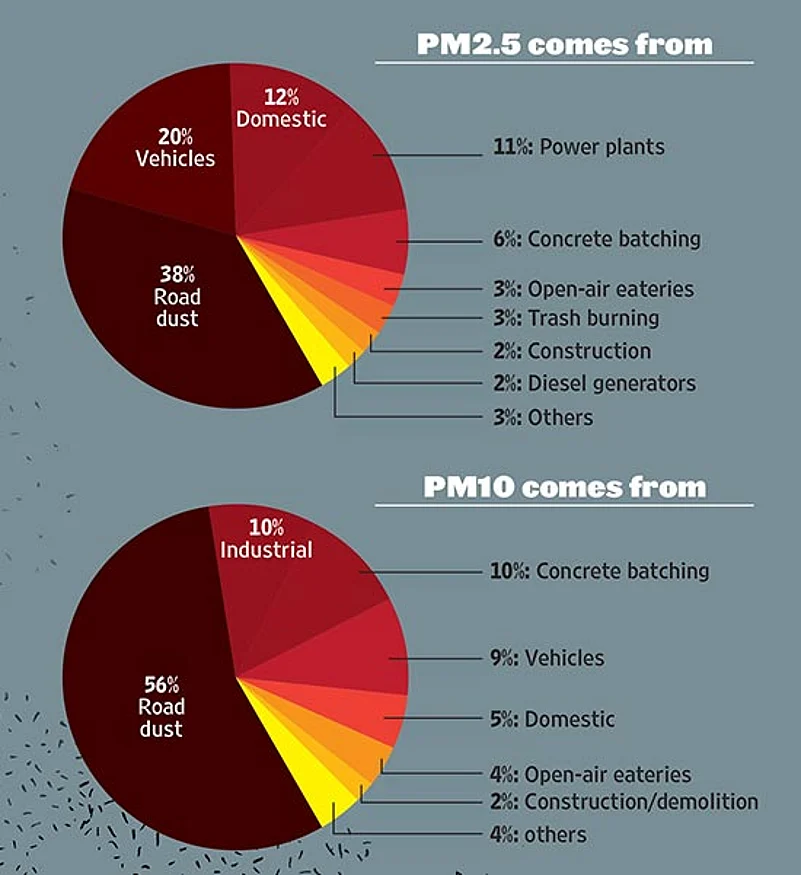

Delhi gets polluted from every conceivable source—burnt rubbish, coal-fired power plants, even roadside barbeques that serve its most iconic snack: tandoori chicken. But the biggest contributor, no doubt, is dust. Climate-wise, Delhi is semi-arid and dusty. A construction boom has only aggravated this situation.

Summers are better. Monsoon showers wash down dust particles. The dreaded smog builds up typically during winters. Winds stall—otherwise a normal characteristic—causing the dust to float longer. The smog takes hold due to a meteorological condition known as ‘inversion’, in which a layer of warm air sits on top of cooler air, trapping it. It’s known as inversion because, normally, cool air tends to exist above warm air. The warm layer then acts like a lid, locking in the smog.

According to a draft version of the CPCB, the step-up plan has been “framed keeping in view the key pollution sources of Delhi”. Many of these sources lie in areas beyond the city’s limits. While vehicles, road dust, rubbish burning, construction, power plants and industries remain constant all-weather sources of Delhi’s pollution, episodes of farm-stubble burning from states such as Punjab spikes during past-harvest periods.

“The plan won’t simply switch off all pollution,” says Anumita Roychoudhury, executive director of the Centre for Science and Environment, a Delhi-based think-tank whose inputs have gone into the plan. “The idea is to ensure that steps that can be taken are taken during the bad days, so we don’t add to the pollution. That’s how it is going to work.”

A smog-alert warning system is built into the mechanism. Once an alert is on the way, “necessary preparations, including identification of sources and action plan, should be ready at least four weeks, and actions initiated at least two weeks, in advance of anticipated critical pollution days”.

What happens when pollution reaches critical levels—for instance, if PM2.5 levels cross 300 microgram per cubic metre or PM10 levels cross 500, five times above the standard, and persist for 48 hours or more? Such counts relate to the “severe” or “emergency” category. “Different levels of action are linked to different levels of pollution,” says Roychoudhury. “An important principle is that during the four winter months—October to February—measures listed against ‘very poor to severe’ conditions will be activated automatically.”

Multiple agencies will swing into action. At the worst levels, movement of trucks other than those carrying essential items, will get suspended. Construction will be halted. The odd-even vehicular road-rationing system will kick in. Moreover, brick kilns, hot-mix plants and stone-crushers will be shut down. The Badarpur power plant, Delhi’s only remaining coal-fired facility, will be closed and power output from gas-based plants cranked up to make up for the capacity loss.

“An IIT Kanpur study shows that apart from the Badarpur plant, 13 thermal power plants within 300 km of Delhi need to be regulated to make a significant difference,” says Sunil Dahiya of Greenpeace India. “So it is important the plan includes those too.” For the first time, differential pricing will be introduced on public transport and for parking. People travelling at peak hours will have to pay more.

At slightly lower levels of pollution, expect bans on diesel generators and roadside open eateries. Residents’ welfare associations will need to provide electric heaters to night watchmen, so that they don’t burn wood. Dust-control measures, such as watering, road sweeping and stringent emission controls at power plants also apply. Garbage burning will be suspended.

In all, there will be six categories of air quality indices, each correlating to a particular pollution level—good, satisfactory, moderately polluted, poor, very poor or severe. The monitoring will be overseen by a task force and follow a “linear” technical-to-bureaucratic management pattern. All it means is that the CPCB and the Met department will provide air data. This information will be processed by an agency called the Environment Pollution Control Authority. It will then be passed on to a joint panel of chief secretaries of all states, which will implement their part of the plan.

Analysts say the action plan should be extended to the entire Indo-Gangetic plains—home to about one-seventh of humanity—in order to be effective. A parallel longer-term strategy is needed too. The current one, too, might succeed if it is not undertaken as mere lip service.

***

Why Delhi Is One Of The Most Polluted Cities Globally

Delhi’s overall annual mean pollution

- PM2.5: 122 µg/m3

- PM10: 229 µg/m3

WHO permissible annual mean pollution

- PM2.5: 10 µg/m3

- PM10: 20 µg/m3

The Clean-Up Act: How It Will Work

Severe-category steps

- Ban on trucks, other than those carrying essential items

- Odd-even road-rationing system kicks in

- Construction to be suspended

- Brick kilns, hot-mix plants and stone-crushers to be shut

- Badarpur power plant to be shut

- Differential pricing on public transport, with peak-hour commuters paying more

Poor, very-poor category measures

- Ban on diesel generators, open eateries, rubbish burning

- RWAs to provide provide electric heaters to watchmen

- Dust-control measures, road sweeping

- More stringent emission controls