Climbing atop a wooden stilt Suhas Mhatre keeps a watch over his grape farm in Maharashtra’s Sangli, as a dizzying heat wave takes hold. Another pair of unflinching eyes is recceing his farm this summer—that of an agriculture drone, flying just under 150 feet. The exercise is part of a hi-tech national mission to map key horticulture regions across 180 districts. It’s an unusual sight, Mhatre says over the phone. Never before in India have drones flown over grape fields, and this one is sweeping the air over select locations in his district.

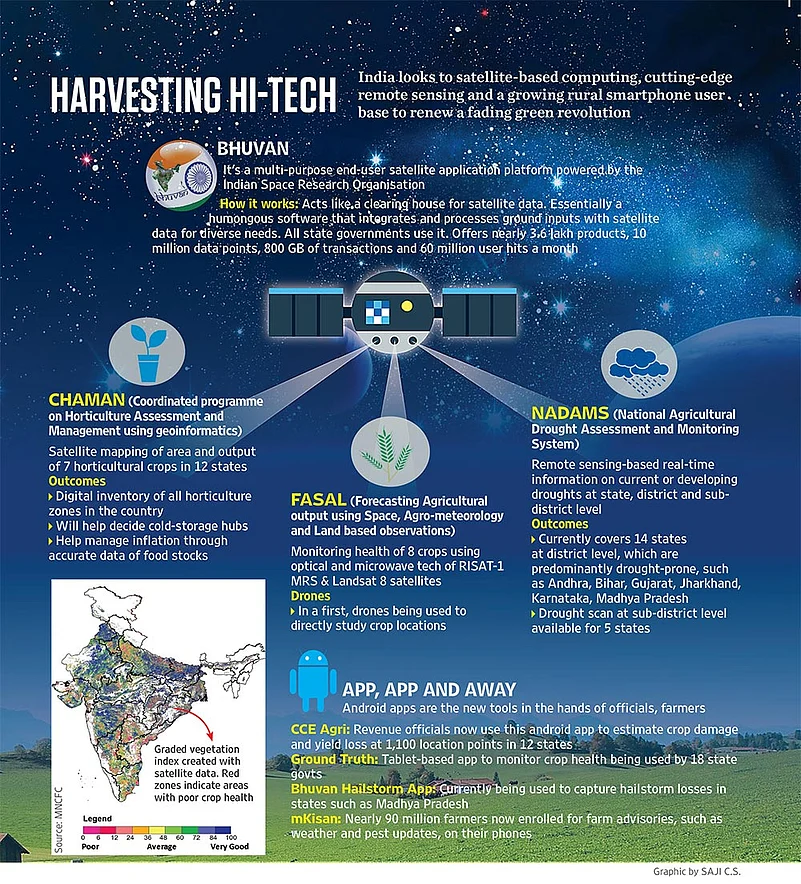

To address challenges of India’s largely antiquated agriculture sector, the government is quietly turning to scientific prowess, harnessing everything from android apps and drones to satellites.

Amid farmer protests in two states, the country’s chief economic adviser, Arvind Subramanian, revealed this past week that the median monthly farm household income was still a paltry Rs 1600. Robust agriculture growth can cut poverty twice as fast as industrial growth in countries with large agriculture-dependent populations. Yet, a majority of Indian farmers—who are classified as small and marginal—are tied to low incomes.

Despite these basic problems, authorities say they are junking traditional practices of analysing agriculture and turning to new technologies to estimate output and demand and supply, as well as to deal with newer challenges, such as frequent weather shocks. Three of the past five years saw extreme weather events, such as drought and unseasonal hail. But the ground data on agriculture is often unreliable; therefore, when droughts crimp output and food prices soar, authorities often struggle to figure out precise stocks. Consequently, it’s hard to tell if prices have edged up due to hoarding by profiteering traders or because of a real supply crunch.

Farmers who qualify for drought compensation are paid off well after the next season because the losses take time to be estimated. It’s done through a British-era method called ‘crop-cutting’, where damaged crops are cut and weighed to estimate yield losses. These are typical problems where, scientists say, the drones could be of help.

“Data from the drones will help build a national inventory of major horticulture crops,” says Sunil Dubey, a senior scientist at the Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Centre (MNCFC). This will give better output estimates. The project is being run in coordination with 12 state horticulture departments.

The inventory will help decide where cold-storage facilities are needed. Data from the drones is also being analysed to develop more and more precision farming models.

“If we are interested in studying, say, just the rice crop, a digital image is taken and uploaded on a satellite-based geo-portal platform called Bhuvan,” says Dubey. One of India’s several Bhuvan-linked satellites matches this with other similar crops across the country, producing quick results. This process can be repeated across seasons to get instant location-based data to analyse crop health.

Satellite data is now officially used for output estimates of horticultural crops such as potato, onion, tomato, chilli, mango and banana. These items play an important role in food inflation. Agriculture departments in states are now making local-level action plans based on geographical information system tools. The data will also help in deciding newer sites where horticulture could be more profitable for poor farmers.

In five potato-producing states—Bihar, Gujarat, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal—production estimates are now through satellites. Policymakers are focusing on horticulture because data shows that more and more small farmers are taking to it. In a path-breaking trend, horticulture output last year outstripped foodgrains production for the fifth year in a row.

India’s growing cellphone subscriber base, estimated at one billion, is also proving fortuitous. At 400 million, India’s smartphone users, who subscribe to data, now outnumber the US’s. Nearly 150 million of them are rural consumers. It’s a window to push farm advisories. Several android apps are now being used by farmers and officials alike.

Take for instance the 90 million farmers who are now subscribed to farm advisories through the mKisan app, developed by the Pune-based Centre for Development of Advanced Computing.

In key states, revenue officials are being trained to use ‘CCE Agri’, an android app developed by the Mahalonobis National Crop Forecasting Centre to estimate crop losses. Going forward, all compensation under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, the national crop insurance scheme, will have to be based on these hand-held generated estimates.

“When done manually, nearly 9 lakh crop-cutting experiments are required in case of a widespread drought. This is time-consuming,” says senior scientist Karan Choudhary, assistant director at the Mahalonobis centre.

Using artificial intelligence, the android app can give a four-category vegetation index, from good to worse. This can be used by revenue officials to quickly calculate the quantum of losses.

The Bhuvan Hailstorm App, another android application, is designed to assess hailstorm losses. Each of the last three years witnessed a hailstorm event of a significant scale in five states: Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana and Punjab. The app captures field photographs with latitude and longitude, name of crop, date of sowing, date of likely harvesting and source of irrigation. This data automatically gets plotted on to the Bhuvan satellite system for analysis.

Another key app called Ground Truth, is now operational in 1,100 locations, monitored by state agriculture departments for crop conditions. “Pest control is a major area. With satellite-backed data via high-res images, we get information directly over an affected crop region,” says Shalini Saxena, another government scientist.

The information collected by these new age devices will provide newer insights on the challenges in farming. In order to address the problems of small farmers, however, experts feel that technology would deliver if it is customised to their needs first. “Small and marginal farmers are complete strangers to technology,” says Gulab Chand Rai, a former professor at Punjab agricultural university who headed a farmer commission. A sobering contrast to these hi-tech interventions are surveys like the landmark Socio-Economic Caste Census of 2015 which showed that only four per cent of rural farming households had mechanised farms.