English language readers might find the words Lapujhanna or Babban Carbonate awkward or, worse, offensive to some extent if they are not from a mofussil or a qasba. I have always found these nomenclatures a bit derogatory; mofussil sounds like muflisi in Urdu, which means poverty. Lapujhanna and Babban Carbonate, as you might have guessed, are Hindi words and, more precisely, the names of two Hindi books by Ashok Pande that were recently published. Hind Yugm, the publisher of Lapujhanna, had to go for a reprint within a week of publishing the book because of the unexpected interest of readers in it. It happens rarely in Hindi except maybe for Surendra Mohan Pathak. So, who is Ashok Pande and why should one read his books? As someone who keeps an eye on the new books coming in Hindi, I would say, he is a force to reckon with despite the fact these are the first of his two prose writings in the last twenty years. To know him and his writings, we must go a little back in time.

Imagine Nainital, Ramnagar and Haldwani of the 1980s and think of a youngster, who is trying to complete his studies, and gets introduced to the iconic Hindi writer late Viren Dangwal. With Dangwal, he learns the nitty-gritty of not only writing but about world literature at large. As he starts reading, he is also keen to publish — as it happens with any youngster — and finds it easy to write a book of poetry. All the big names of Hindi literature such as Dangwal, Manglesh Dabral, Vishnu Nagar and Trilochan Shastri come to launch his poetry collection: Dekhta Hoon Sapney, in a publicised ceremony in Nainital. Everyone sings the praise of the book, but then nothing happens. Almost nothing. The youngster is perplexed. There is nothing he earns with that book except praises. It must have been a time of confusion for the young man, but he is already involved in translations without any commitment from any publisher. He has just been introduced to Irving Stone’s biography of Van Gogh, Lust for Life. It becomes an obsession, and he doesn’t know what to do. He decides to translate. What else could he do? It finds a publisher after a while.

By the time it publishes, the youngster has matured. He has saved money from odd jobs and travels widely and wildly. Whatever he earns from any kind of editing jobs, writing assignments, he saves money, watches international cinema, reads, and travels. On one of his trips to South America, he learns Spanish and translates many stories from Spanish into Hindi. Nothing gets published as no one is willing to secure the translation rights. Securing money for the translation is another part where he finds himself handicapped. In between, he travels to Bombay for work, comes back to the hills and starts doing what he could do: Write and translate whatever he feels like. Now, the youngster is a mature man and knows much more about world literature because of his travels around the world. He knows the limitations of Hindi literature and the politics of publishing. Rather than cribbing about it or using his connections, he chooses to keep himself to the small town and write something which has not been written yet and Lapujhanna comes into existence.

It is a story of four friends set in the town of Ramnagar, written from the point of view of one of them; the narrator is part of that group — they are friends because of their interest in food, films, and, of course, girls. As you enter this world, you encounter the names of characters you might not have even heard of, but somewhere they feel real. For instance, a character called Lafattu, who stammers; no one plays with him as he steals. The language of Lafattu is one of the highlights of the books as he is an expert of everything, especially how to steal money from home and temples, and you can only laugh when you read something like this: “apne paitte kato uncle aur apna taam talo,” meaning 'apne paise kato uncle aur apna kaam karo'.

Then you meet Bagadbilla, the eldest of the friends, Lalsingh, who works at a roadside dhaba with his father. All fans of Jeenataman (Zeenat Aman), the men dream of marrying every new girl they come across in Ramnagar. The novel, before getting published, came into being as a blog in 2012. Pande must have realised with his knowledge of the Hindi publishing world that no one will be interested in publishing his novel which is on a different trajectory of honest, happy life in a small town rather than the typical middle-class sad/inspirational/conflict love story written by Hindi authors. “I wanted to write about the happy childhood I had, the people I grew up with. Despite reading several Hindi books, I never found such characters in any of them, and I guessed that the publishers might not be interested in them. Blogging was new and I started writing it and it became a huge hit in 2012 with people writing me long letters,” says Pande. Still, it took nine years to get that story published as a book and now in its second edition within a week, Pande is surprised, “I never thought that people will give such a huge response. I am overwhelmed and don’t know what to say.”

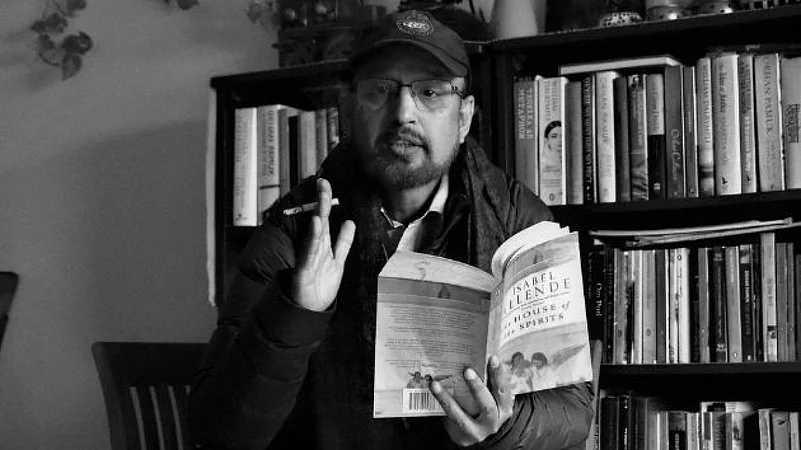

Pande is not new to fame. His writing on Facebook is a craze among young and old readers and his admirers confess that they come to the social media site only to read him. For Pande, Facebook is just a medium. He writes and forgets about writing as he has many things to do. An avid walker who likes to play with children, he is the father of a girl, who lives in Austria with her mother. Pande’s love life has another interesting story about which I came to know recently. Many years ago, an anthropologist named Dr Sabine Leder from Vienna University came to Uttarakhand to do research on Shauka tribe. She was looking for a guide who could speak English and had to be a local. A difficult proposition. Someone introduced Pande, who had just come back from his Europe trip, to Sabine. The trip to Darma Valley and Leder’s research on Shauka tribe was published later. For Pande, the trip to Darma Valley with Leder literally changed his life as they decided to stay together. Pande also wrote diaries on the Darma Valley travels and intends to publish them in Hindi. “If a publisher agrees,’’ he says.

But being a traveller, writer and what we call in Hindi, a “yaaron ka yaar”, Pande is also known as one of the best translators. His translation of Pietro Citati’s biography of Kafka is legendary though yet to be published. Other than Lust for Life, his translations have not seen the light of the day. Some fortunate people like me somehow got their hands on Citati’s translation and are amazed to see the way Pande has translated. Another of his impeccable translation is of The Fragrance of Guava by Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza based on the interview with Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Again unpublished. He might have 15 to 20 manuscripts of translations in his big box which he refuses to publish if the publisher does not secure the translation rights and pay him a decent amount of money. Even with books, he comes across as a reluctant person not because he is not interested in getting published, but because he is averse to literary politics.

His reticence is understandable. After reading him, when I called him and asked for his number so that I could share it with some publishers, he smiled without any comment. He just said, “Try if you want to.” I tried. Nothing happened. There might be others like me who must have approached publishers and requested them to publish Ashok Pande. So, what happened now that he got three of his books published in January 2022? He says, “After 2020, when Covid struck, I felt like everything was crumbling around me. Something changed inside me. It is very difficult to explain. I must have felt that whatever I have written will remain in these boxes so I thought to give the manuscripts to anyone who is willing to publish it decently. Not the translations though. Those require securing the translation rights and publishers don’t seem to be willing. I decided to get my own writings published. Money was not the motivation. It was this feeling of the world coming down that pushed me to actively send the manuscripts or write for a mobile app.” Covid has given us nightmares, but it has given Hindi readers books by Ashok Pande. And he is here — in the Hindi literary world — to stay. As his books get talked about and he gets his due recognition, Pande is surprised but not overwhelmed: “I have seen enough in the world. My job is to write. Nothing else. I am just finalizing whatever I think should get published. There is no other thought in my mind right now.”