On the night of December 22-23, 1949, Lord Ram’s idols miraculously appeared inside the Babri mosque in Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh’s Faizabad district. Those were tumultuous times for Hindutva activists, who had been facing extraordinary trials and tribulations since Independence and Partition. Less than six weeks earlier, on November 15, 1949, Nathu Ram Godse and Narayan Apte, Mahatma Gandhi’s assassins, had been hanged at the Ambala Central Jail. Before their execution, the two prisoners recited the 11th and 15th chapters of the Bhagavad Gita and the first four lines of the RSS prayer. While climbing the gallows, they are reported to have shouted “Akhand Bharat amar rahe” and “vande mataram”! The bodies were cremated in the jail by prison authorities according to Hindu Sanatanist rites as per their last wishes. Requests by family members to be present at the cremation had been turned down. Godse and Apte had also expressed their wish to have their ashes immersed in the river Indus, an indivisible part of Bharat mata.

The appearance of the idols brought a sense of closure to Hindutva activists, who had faced an extremely challenging environment in the 22 months since Gandhi’s murder. Prominent RSS leaders had been arrested. The government saw the RSS as the volunteer arm of the Hindu Mahasabha, even though ties between the two organisations had been tenuous.

The RSS was banned on February 4, 1948, together with its newspapers and affiliated bodies, and disciplinary action had been taken against government employees with RSS sympathies in many states. The official communiqué on the ban had stated that the RSS “indulged in acts of violence involving arson, robbery, dacoity and murder, and…collected illicit arms and ammunitions”. This referred to its role in Punjab, Delhi and other north Indian cities during the Partition riots in which its members had participated vigorously in “Hindu defence”, safeguarding refugee convoys, trains, camps and neighbourhoods.

After Gandhi’s murder, RSS chief M.S. Golwalkar had condemned the murderers and asked all shakhas to suspend activities for 13 days. When he was arrested on February 8, 1948, he instructed RSS cadre to avoid any violence and temporarily disbanded the organisation. Mass arrests of leaders and cadre followed, extending to over two lakh people. No proof of Golwalkar’s link with the Gandhi murder case was furnished. He was released after the six-month statutory period of detention on August 5, but instructed not to leave Nagpur. On September 24, he asked Nehru to lift the ban on the RSS. Stating that “a mass of information” existed on RSS involvement in “anti-national and communal activity”, Nehru replied that he should contact then home minister Sardar Patel. A protracted and contentious correspondence followed and Golwalkar was arrested again on November 15.

When Golwalkar (right) asked Nehru to lift the ban on the RSS, he was told to contact Sardar Patel

With the help of several mediators in the months that followed, RSS leaders secured the lifting of the ban on July 11, 1949, but only after adopting a written constitution that stated the RSS “has no politics of its own and will be wedded to purely cultural work”. Golwalkar swore loyalty to the Indian Constitution, respect for the national flag, and eschewed violence and secret methods. On July 13, he was released from jail and the Organiser, the RSS organ, resumed publication on August 22.

The prohibition on taking part in politics, however, proved to be restrictive. The main political body, the Hindu Mahasabha, had gone into a state of disarray after Gandhi’s murder. Hindutva support had remained intact only in Bengal, due to the influence of Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Moreover, ideologically and organisationally, Hindutva remained on the defensive and in disarray due to the ideological onslaught it had faced after Gandhi’s murder. Leading the charge had been Nehru himself. “Those who were demanding a Hindu State have killed the greatest of all Hindus,” he had said at an enormous public meeting in Delhi just two days after the murder. However, a new opportunity, a beginning, was just round the corner.

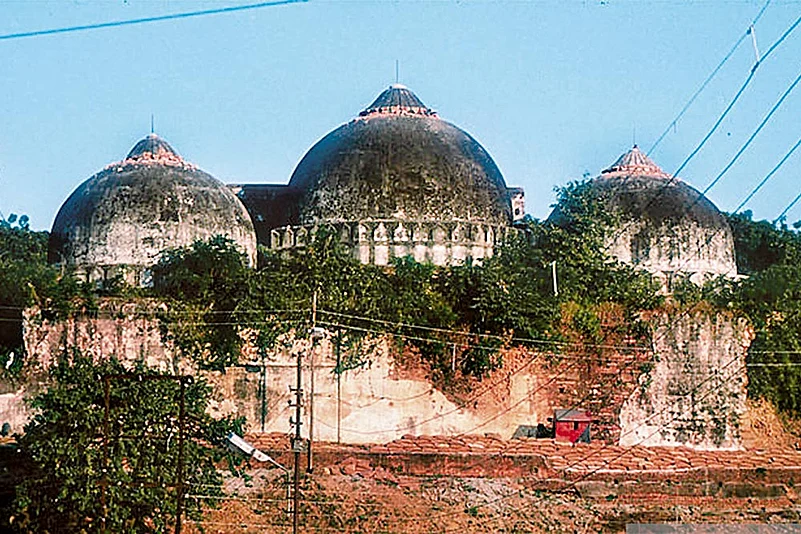

The ‘miracle’ of December 22-23, 1949, was the climax of a nine-day non-stop recitation of Ramcharit Manas just outside the Babri mosque, organised by the Akhil Bharatiya Ramayana Mahasabha, with Mahant Digvijay Nath of Gorakhnath matth reportedly playing a prominent role. The mahant had recently been released from prison for his hate-speech against Gandhi just before his assassination. Next morning, on December 23, then Faizabad DM K.K.K. Nayar relayed the news to UP chief minister Govind Ballabh Pant via a radio message: “A few Hindus entered Babri Masjid at night when it was deserted and installed a deity there. DM and SP and force at the spot. Situation under control. Police picket of 15 persons was on duty at night, but did not apparently act.” With the complicity of Nayar and his deputy, Guru Dutt Singh, Hindus had entered the mosque at night to convert it into a temple by installing Lord Ram’s idol.

As soon as Nehru learnt of the incident, he sent a telegram to Pant: “I am disturbed at developments in Ayodhya…. Dangerous example is being set there, which will have bad consequences.” A furious Nehru asked the CM “to undo the wrong”. Chief secretary Bhagwan Sahay and inspector general of police B.N. Lahiri frantically sent instructions for the removal of the idols. However, as the person in charge, Nayar refused to obey orders due to the “suffering it will entail to many innocent lives”. He was relieved of his charge. Later, both Nayar and Singh pursued a political career with the RSS-affiliated Jan Sangh.

Nehru continued to follow up with Pant through urgent letters and telephone calls. On January 7, 1950, he conferred with C. Rajagopalachari, the governor-general who had written to him on this issue. He reported that Pant was “very worried and he was personally looking into this matter. He intended taking action, but wanted to get some well-known Hindus to explain the situation to people in Ayodhya first.”

By then, Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy prime minister and in-charge of home affairs, was fully involved in the case and Pant preferred to deal with him directly. Patel, who had already visited Lucknow, took the final call on the matter. “The issue is one that should be resolved amicably in a spirit of mutual toleration and goodwill between the two communities,” he wrote in a letter to Pant dated January 9. “I realise there is a great deal of sentiment behind the move that has taken place. At the same time, such matters can only be resolved peacefully if we take the willing consent of the Muslim community with us. There can be no question of resolving such disputes by force. In that case, the forces of law and order will have to maintain peace at all costs. If, therefore, peaceful and persuasive methods are to be followed, any unilateral action based on an attitude of aggression or coercion cannot be countenanced.”

In effect, this meant maintaining the status quo in Ayodhya. Nehru chaffed at the state of affairs, asked Pant to keep him regularly updated, and offered to personally visit Ayodhya. Although Nehru kept a watch, he was soon beginning to express his dismay at Pant’s inaction, appeasement and weak handling of the situation. On April 17, 1950, he complained to Pant: “The recent occurrences in UP have greatly disturbed me…. Atmosphere in UP has been changing for the worse from the communal point of view…. Indeed, UP is becoming a foreign land to me. I do not fit there. The UP Congress, with which I have been associated for 35 years, now functions in a manner that amazes me.” Nehru then drew upon a biblical metaphor from the Gospel of St Matthew to reprimand Pant and the UP Congress for deviating from its ideals: “If the sea loses its saltiness, wherewith shall it be salted.”

Two weeks later, on May 1, 1950, Nehru again conveyed to Pant that he was “depressed” with the state of affairs in UP and “invited” him to New Delhi as a cabinet minister. He even offered Pant the finance ministry at the Centre, expressing his desire for an immediate change. Pant, however, outmanoeuvred Nehru by lobbying support within the Congress ‘high command’ (most notably, Patel) and leading figures of the UP Congress.

In retrospect, it’s still a puzzle why Nehru failed to act more decisively on Ayodhya. A plausible answer may be three-fold. Firstly, it is related to the extremely fluid state of affairs within the Congress between August 1947 and December 1950, during which Nehru had to share authority with Patel, whose writ ran unmistakably over the ‘high command’ and who had his acolytes in practically every state. Secondly, Nehru had a deep understanding of the political ground realities in the UP Congress, whose ethos had been shaped by leaders such as the late Madan Mohan Malaviya, Purushottam Das Tandon and Sampurnanand, as well as local activists like Baba Raghav Das.

Leaders like Pant exercised authority by conciliating and appeasing the right-wing elements, who had deep ideological affinities with Hindutva. Finally, it was characteristic of Nehru to trust his own colleagues of over 30 years—Patel and Pant—to do the right thing within a democratic system. In fact, one can see a striking parallel with Atal Behari Vajpayee’s handling of the post-2002 situation in Gujarat.

It was only after Patel’s death in December 1950 that Nehru could assert himself more vigorously to deal with the Congress right-wing. In late 1951, he instigated Tandon’s resignation as Congress president to take direct control over the party machinery—a necessary preclude to the first national elections of 1951-52. A victory in 364 Lok Sabha seats in a house of 489 gave him the political authority he needed so badly, and which he exercised until the humiliation inflicted by the Sino-Indian war of 1962.

***

Saffron In Sepia Tint

Indira Gandhi made it a point to visit Hindu temples and courted sadhus such as Devraha Baba of Vrindavan, who predicted her party would bag 300-plus seats in 1980. She accepted an invite to launch the VHP’s Ekatmata or Ganga Jal Yatra in 1983. When she died, RSS leader Nanaji Deshmukh said, “She alone could run the decadent political system of our corrupt and divided society.”

In 1986, Rajiv Gandhi got Babri Masjid’s lock opened and allowed puja inside it. In November 1989, he did the Ram temple’s stone-laying ceremony before starting his election campaign from Ayodhya to create a “Ram rajya”.

On the eve of the Babri Masjid’s demolition in 1992, then PM P.V. Narasimha Rao held a meeting with RSS and VHP leaders.

(The writer is associate professor in the South Asian studies programme at the National University of Singapore)