Our Hinduism is not Hindutva, says the present-day Congress, whose leaders visit temples and wear appropriate ‘Hindu’ clothes for the visit. The Congress should not forget the idea that Hindustan is for Hindus has not found many takers in India—even though Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, in the aftermath of the Great Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, did assert that everyone living in Hindustan was of the Hindu Qaum irrespective of their religion. Of course, the Muslim League—the party that led to the formation of Pakistan, the only separate nation for Muslims in the world—always held the Congress to be a ‘Hindu’ party.

If electoral success is taken to be the main indicator of which community supports which political party, then we have the results of the first popular elections of 1936-37. The Congress failed to get a majority in Punjab and Bengal, the two Muslim-dominated provinces of colonial India. It failed even on other reserved seats. In Punjab, where there was a third religious community that had been given separate electorates, Jawaharlal Nehru had to face the ignominy of having the Congress candidate he personally campaigned for being defeated on the Sikh seat of Sarhali by the young and unknown Sardar Partap Singh Kairon of the Akali Dal.

Ten years later, in 1946, the Muslim League, with its demand for a separate country for Muslims, would be able to sweep the polls in Punjab. The maliks—tribal leaders dominating the Muslim tribes of the North West Frontier Province (currently known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa)—did not much appreciate the coming of the Muslim League. They looked up to Nehru, then the premier of the interim government and also the minister handling foreign policy, to find them some way of remaining with India after the formation of Pakistan. With no answer forthcoming, the maliks had to accede to Pakistan.

The Gandhi-led non-cooperation movement sought to combine Khilafat with the Rowlatt agitation

Since its first year of existence, the Congress had to battle the charge that it was a party of Hindus. While the Congress claimed to represent all Indians, Sir Syed, the most prominent Muslim of his times, a rationalist, promoter of science, and founder of the Mahomedan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh, urged all Muslims to keep away from the Congress lest they be overwhelmed by Bengali Hindus, who, in his estimation, dominated the party. He warned Muslims that consorting with such persons would bring about the same disaster as the 1857 rebellion, when it was the Muslim grandees who suffered the most even while the rebellion was mostly the doing of Hindu sepoys.

When the group of English-educated lawyers, journalists and social reformers assembled in Mumbai in 1885 to form the Indian National Congress, they were keenly aware of the concerns Sir Syed had expressed. One of the first resolutions passed in the first congress specifically mentioned promotion of communal amity between Hindus and Muslims as its objective. This was important as there were only two Muslims among the 72 delegates—Rahimtulla M. Sayani and A.M. Dharamsi, both from Mumbai.

At the second congress in Calcutta, organised the next year, Maulvi Sharfuddin, a delegate from Bihar, asserted that the Congress was not a Hindu body, but a truly national one, and that the people of India stood by it irrespective of race and creed. The third congress was presided over by a Muslim, Badruddin Tyabji. He was at great pains to assure Muslims that they need not fear that the Hindu majority would override their interests. Tyabji underlined the principle adopted by the Congress: Any proposition to which Muslims disagreed would not be considered.

The number of Muslim delegates in the Congress kept on increasing. It was almost 10 per cent in 1886. By 1890, the proportion of Muslim delegates had gone up to almost 20 per cent. Rashid Ahmad Gangohi, one of the founders of the Dar ul Uloom in Deoband, also spoke up against Sir Syed’s advocacy of separate Muslim interests. Gangohi urged Muslims to cooperate with the Congress.

By the time Sayani became Congress president in 1896, the proportion of Muslim delegates had gone below 10 per cent. In his presidential remarks, he commented that the decline was because of the misunderstanding that the Congress was a Hindu party, and that all Muslims were against the Congress. He attributed the scant Muslim presence to the rumour that Muslims who joined the Congress would lose their religion. He also denied the rumour that the Congress was planning to overthrow British rule and establish Hindu rule over India.

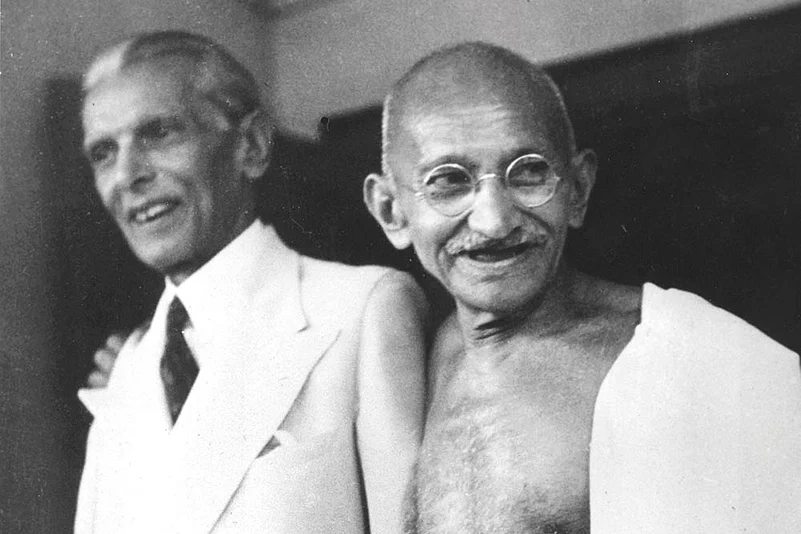

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan urged all Muslims to keep away from the Congress; (right) Badrudddin Tyabji tried to assure Muslims that they need not fear the Hindu majority

Meanwhile, Sir Syed floated the Muslim Educational Conference with the objective of promoting modern education among Muslims and conveying what he thought were Muslim concerns to the colonial authorities. In the wake of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal, it transformed into a political party—the Muslim League. The League demanded that the government set up a Muslim university, which was rejected by the government on the principle that it did not permit denominational universities. The stated objectives, outlined in its constitution, were to protect Muslim rights and liberties, educate Muslims about the actions of the government, and discourage violence. When communal violence happened in Bengal in 1908, the Muslim League remained indifferent.

The Congress faded away as the Swadeshi movement petered out. So did the Muslim League. In 1913, the League was rejuvenated with the arrival of a lawyer—Mohammed Ali Jinnah of Mumbai. He worked ceaselessly with like-minded friends within what remained of the Congress to find ways of making the Congress and the League work together.

Motilal Nehru, then heading the Allahabad branch of the Home Rule League, explained to his son, the lawyer Jawaharlal, that nothing effective could be done in India until some solution for the Hindu-Muslim question had been found. Meeting at Nehru’s house in Allahabad, the All India Congress Committee managed to create a scheme whereby Muslims were recognised as a minority in India and offered a larger proportion of seats in the provincial legislatures. On the basis of this formula, the leaders of the League, at the urging of Jinnah, agreed to join the Congress in demanding greater autonomy for India. The Lucknow Pact, as it came to be known, was the highpoint of cooperation between the Congress and the Muslim League. Sarojini Naidu called Jinnah the “Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity”.

At this stage, neither the League nor the Congress had much sympathy for the common people of India. They ignored reports about young men from Punjab being press-ganged into joining the army. Instead the leaders went out of their way to ensure a regular supply of cannon fodder for Britain’s war in Europe. Even Gandhi spent two months in 1918 persuading Gujarat’s young men to join the so-called ‘war effort’.

Gandhi did bring about a change in the political culture of the Congress. He created activities that involved the masses. One of his first large-scale political actions was in conjunction with the most popular movement among Muslims, the Khilafat. Gandhi persuaded the Khilafat Conference to launch a countrywide strike on Khilafat Day to protest against the treatment meted out to the Khalifa of Islam after the defeat of Turkey in the First World War. The relative success of the Khilafat Day protest encouraged him, a little later, to use the Congress platform to launch another nationwide protest—the Rowlatt satyagraha against the Rowlatt Act. The non-cooperation movement that began in August 1920 sought to combine both the protests.

When Maulana Abdul Bari suggested Muslims should give up cow slaughter in deference to Hindu sentiments, Gandhi disagreed. He argued that the Khilafat cause was just, and that Hindus needed to support it unconditionally and not bargain on the question of cow slaughter. Gandhi explained to his secretary, Mahadev Desai, the importance of conceding: “If we go on remembering old scores, we would feel that (Hindu-Muslim) unity is impossible, but at any cost we ought to forget the past. History teaches us that these things have happened the world over, and that the world has forgotten them because public memory is always short and forgiving.”

Something of what Gandhi had in mind was witnessed in April 1919, at Gujranwala in Punjab, during the Rowlatt satyagraha. A dead calf was found on a railway bridge. People—Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs—said the British had done it to create communal dissension. They ignored the dead calf and continued to work in unison to occupy government buildings and burn them down, shouting ‘Hindu-Musalman ki jai’, ‘Mahatma Gandhi ki jai’.

Jinnah was one Muslim leader who disagreed vehemently with the Congress participating in a religion-based movement like the Khilafat. He, along with the Muslim League, walked away. Nehru would recall in his autobiography the annoyance Jinnah had expressed. But, Nehru would comment, the League did not represent the masses, the Khilafat movement did.

A few years later, with greater prospects of Indians getting self-governance in sight, Jinnah formulated 14 points as the basis of the Muslim League once again cooperating with the Congress in their search for swaraj. The Congress rejected Jinnah’s points. However, when the British made a similar proposition of creating religion-based constituencies—in the Communal Award of 1932-33, the Congress silently accepted it. The task of condemning the award was left to the Akali Dal, which claimed to represent Sikhs and argued that it would put the Sikhs at a disadvantage vis-á-vis Punjab’s majority Muslim community. The electoral defeat of Nehru’s candidate at the hands of Kairon followed in 1937.

The one lesson the Congress did not seem to learn from such constant failures was that primordial loyalties like religion are an ineffective way of creating nationwide unities among people in India, and that any attempt to promote such loyalties only results in hostility and violence.

***

The Holy Fire Of Free India

Hours before the inaugural session of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad and Jawaharlal Nehru participated in a special ‘havan’ where hymns were chanted, holy water sprinkled on them and their foreheads were smeared with red vermillion ‘mangal tilak’ before they proceeded to the assembly. Nehru’s unsparing attack on the RSS notwithstanding, on occasion he also praised them, especially when Pakistani troops entered J&K in 1947 and after the 1962 Sino-Indian war. Acknowledging the services rendered by them, he also invited the RSS to participate in the 1963 Republic Day parade.

(The writer is professor, department of history, Panjab University, Chandigarh.)