Sanjay Kak’s new documentary Jashn-e-Azadi ("How we celebratefreedom") isaimed primarily at an Indian audience. This two-part film, 138 min long,explores what Kakcalls the "sentiment", namely "azadi" (literally "freedom")driving the conflict in the India controlledpart of Kashmir for the past 18 years. This sentiment is inchoate: it doesnot havea unified movement, a symbol, a flag, a map, a slogan, a leader or any oneparty associatedwith it. Sometimes it means full territorial independence, and sometimes itmeans otherthings. Yet it is real, with a reality that neither outright repression norfitful persuasion fromIndia has managed to dissipate for almost two decades. Howsoever unclear itspoliticalshape, Kashmiris know the emotional charge of azadi, its ability to keepalive in everyKashmiri heart a sense of struggle, of dissent, of hope. It is for Indianswho do not knowabout this sentiment, or do not know how to react to it, that Kak has madehis difficult,powerful film. And it is with Indian audiences that Kak has already had, andis likely tocontinue having, the most heated debate.

Between 1989 and 2007, nearly 100,000 people--soldiers and civilians, armedmilitants and unarmed citizens, Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris--lost theirlives to theviolence in Kashmir. 700,000 Indian military and paramilitary troops arestationed there, thelargest such armed presence in what is supposedly peace time, anywhere in theworld. Bothresidents of and visitors to Kashmir in recent years already know what Kak’sfilm bringshome to the viewer: how thoroughly militarized the Valley is, criss-crossedby barbed wire,littered with bunkers and sand-bags, dotted with men in uniform carryingguns, its roadsbearing an unending stream of armoured vehicles up and down a landscape thatused to becalled, echoing the words of the Mughal Emperor Jehangir, Paradise on earth.Other placesso mangled by a security apparatus as to make it impossible for life toproceed normallyimmediately come to mind: occupied Palestine, occupied Iraq.

Locals, especially young men, must produce identification at all the check-poststhatpunctuate the land, or during sudden and frequent operations described by thedreadedwords "crackdown" and "cordon and search". Kak’s camera shows usthat even the mostordinary attempt to cross the city of Srinagar, or travel from one village toanother is fraughtwith these security checks, as though the entire Valley were a giganticairport terminal andevery man were a threat to every other. As soldiers insultingly frisk folksfor walking about intheir own places, the expressions in their eyes--anger, fear, resignation,frustration, irritation,or just plain embarrassment--say it all. In one scene men are lined up,and some of them gettheir clothes pulled and their faces slapped while they are being searched.Somewherebeneath all these daily humiliations burns the unnamed sentiment: azadi.

One reason that there is no Indian tolerance for this word in the context ofKashmiris that the desire for "freedom" immediately implies that its opposite isthe case: Kashmir isnot free. By the logic of the Indian state, India is free and Kashmir is apart of India, ergo,Kashmir too, must be free. But Kak’s images provide visual attestation forsomethingdiametrically opposed to this logic: the reality of occupation. Kashmir isoccupied by Indiantroops, somewhat like Palestine is by Israeli troops, and Iraq is by Americanand coalitiontroops. But wait, objects the Indian viewer. Palestinians are Muslims andIsraelis are Jews;Iraqis are Iraqis and Americans are Americans--how are their dynamicscomparable to thesituation in Kashmir? Indians and Kashmiris are all Indian; Muslims andnon-Muslims inKashmir (or anywhere in India) are all Indian. Neither the criterion ofnationality nor thecriterion of religion is applicable to explain what it is that puts Indiantroops and Kashmiricitizens on either side of a line of hostility. How can we speak of an "occupation"whenthere are no enemies, no foreigners and no outsiders in the picture at all?And if occupationmakes no sense, then how can azadi make any sense?

Kak explained to an audience at a recent screening of his film in Boston (23/09)thathe could only begin to approach the subject of his film, azadi, after he hadmade it past threebarriers to understanding that stand in the way of an Indian mind trying tograsp what isgoing on in Kashmir. The first of these is secularism. Since India is asecular country, mostIndians do not even begin to see how unrest in any part of the country couldbe explainedusing religion--that too what is, in the larger picture, a minorityreligion--as a valid groundfor the political self-definition and self-determination of a community. TheValley ofKashmir is 95% Muslim. Does this mean that Kashmiris get to have their ownnation? Formost Indians, the answer is simply: No. Kashmiri Muslims are no more entitledto a separatenation than were the Sikhs who supported the idea of Khalistan in the 1980s.Such claimsreplay, for Indians, the worst memories of Partition in 1947, and bring backthe ghost ofJinnah’s two-nation theory to haunt India’s secular polity and tothreaten it from within.

The second barrier to understanding, related to the struggle over secularism,is theflight of the Pandits, Kashmir’s erstwhile 4% Hindu minority community,following violentincidents in 1990. 160,000 Pandits fled the Valley in that year’s exodus,leaving behindhomes, lands and jobs they have yet to recover. Today the Pandits live, ifnot in Indian andforeign cities, then in refugee settlements that have become semi-permanent,most notably inJammu and Delhi. For Indians, even if they do little or nothing torehabilitate Pandits intothe Indian mainstream, the persecution of the Pandits at the hands of theirfellow-Kashmiris,following the fault-lines of religious difference and the minority-majoritydivide, is a deeplyalienating feature of Kashmir’s conflict. Kashmir’s Muslim leadership hasconsistentlyexpressed regret for what happened to the Pandits in the first phase of thestruggle for azadi,but it has not, on the other hand, made any serious effort to bring back theexiled Hinduseither. In failing to ensure the safety of the Pandits, Kashmir has lost avital connection withthe Indian state--and, potentially, a source of legitimacy for its claimto an exceptional statusas a sovereign entity.

The third major obstruction to India taking a sympathetic view of Kashmir is theproblem of trans-national jihad. Throughout the 1990s, Kashmir’s indigenousmovementsfor azadi have received varying degrees of support, in the form of funds,arms, fighting men,and ideological solidarity, not only from the government of Pakistan, butalso from Islamistforces all across Central Asia and the Middle East. The reality of Pakistanisupport, and thepresence of foreign fighters, from an Indian perspective, damages the claimfor azadi beyondrepair.

Kashmiri exceptionalism in fact has an old history. Yet even if we do not wantto goas far back as pre-modern and colonial times, then at the very least rightfrom 1947, Kashmirhas never really broken away completely like the parts of British India thatbecame Pakistan,nor has it assimilated properly, like the other elements that formed theIndian republic. Thestatus of Kashmir has always been uncertain, in free India. But with theinvolvement of pan-Asian or global Islamist players, starting with Pakistan but by no meanslimited to it, the pastgives way to the present.

India no longer deals with Kashmir as though itwere still the placethat was ruled by a Hindu king until 1947 and never fully came on board theIndian nation inthe subsequent 50 years. It now looks upon Kashmir as the Indian end of theburning swathof Islamist insurgency that engulfs most of the region. In quelling azadi theIndian state seesitself as engaged in putting out the much larger fires of jihad that havebreached the walls ofthe nation and entered into its most inflammable--because Muslim-majority--section.

Secularism, the Pandits and jihad are all very real impediments to Indiaactually beingable to see what is equally real, namely, the Kashmiri longing for azadi. Kakexplained to hisviewers that to be able to portray azadi from the inside, he had to getthrough and past thesebarriers, to the place where Kashmiris inhabit their peculiar and tragiccombination ofresistance and vulnerability, their dream of a separate identity and theirconfrontation withan overwhelmingly powerful adversary. Their misery is palpable but they haveyet to find apolitics adequate to transform dissatisfaction into independence. Kashmirisdo not agree ona singular meaning of the word "azadi". Meanwhile, in the face of bruteoppression, they donot fully fight back, but they do not submit either.

Kak subtly captures their strangeness as a people: they recount how they lostsonsand husbands to a random, ubiquitous and unforgiving violence, and, in themidst ofgruesome narrations, offer the questioner tea. They walk among the dead,through lotscovered with marked and unmarked graves, speaking of the departed in a weirdidiom thatmixes the language of martyrdom with the everydayness of life that mustcontinue. Theirpoets, whether Muslim or Pandit, compose verses that in Kashmiri, Urdu orEnglish carrythe same unmistakable note of pain, even as they mirror a landscape ofmountain lakes,blooming flowers and delicately-hued skies. (A few years ago Amar Kanwar’sdocumentary Night of Prophecy also brought to Indian audiences the same poignancyof poetry writtenby Kashmiris that confronts torture, disappearance and death in a place ofunearthly naturalbeauty). Their traditional entertainers, village bards and clowns, called "PatherBhand",remember their patron, the medieval pir (Sufi saint) Zain ul Abidin,or Zain Shah, and telltales of war and destitution with a mischievous light-heartedness that makesyou cry insteadof making you laugh. Women cover their heads but look at the camera withunnervingdirectness, insouciant, beleaguered but never submissive. These are a wrypeople, partdefeated, part unconquerable.

Their breathtakingly beautiful land stands at the crossroads of East Asian,CentralAsian and South Asian cultures. For centuries, different races, religions andethnicities havetrampled through Kashmir, subduing its people on their way. But the Kashmirilanguagebears little relationship to any other languages of Persia, India,Afghanistan, Tibet or China,its nearest neighbours. Kashmir has always kept its head down as the winds ofhistory haveblown over and across the mountains, turned inward in an isolation that feedsthe desire forazadi but does not provide the political wherewithal, the canniness, to carveout a separatenation in a world where might makes right.

Here the Indian Army arrives, one Indian soldier to every 10 Kashmiris. Here theIndian tourists arrive, as Kak shows us, sledding in snowy Gulmarg, dressingup in "native"costume to have photographs taken in the Mughal Gardens of Srinagar, callingblood-spatteredKashmir a veritable Paradise. Here the sadhus in saffron robes arrive, ontheir wayto the holy shrine at Amarnath, on their annual pilgrimage, invoking, in thesame breath, theHindu god Shiva and the Indian flag, the "tiranga" ("tri-colour").You cannot take awaywhat is ours, say these people. Ah, but you cannot keep what was never yours,either. Indiafor Indians; Kashmir for Kashmiris: this is the fugitive logic that thefilmmaker is seeking tomake explicit.

Kak has set himself a nearly impossible task. He must take Indians with him, onhisdifficult journey, past their prejudices, past their suspicions, past theirvery real fears, into thenightmarish world of Kashmiri citizens, torn apart between the militants andthe military,stuck with the after-effects of bombings, mine-blasts, crackdowns, arrests,encounter killingsand disappearances that have gone on for nearly two decades without pause.

Ibecameinterested in Kashmir at the same time, for the same reason, that Kak beganhisinvestigations: the trial of S.A.R. Geelani, accused and later acquitted inthe December 13,2001 Parliament Attack case. In 2005 I wrote a couple of articles aboutGeelani, a Kashmiriprofessor of Arabic and Persian Literature at Delhi University, for this andother Indianpublications. These earned me denouncements as anti-national, self-hating,anti-Hindu, pro-Pakistani, crypto-Muslim, etc. One letter to the editor even called me aterrorist!Kak has already had a taste of this reaction since the release of Jashn-e-AzadiinMarch, and must expect more of it to be coming his way in the next fewmonths, as his filmis shown widely in India and abroad. In fact, he is sure to get more flakthat I ever got, givenhe is a Kashmiri Pandit.

Aggressively Hindu nationalist, right-wing Panditgroups find Kak’sempathy for Kashmiri Muslim positions infuriating, a "betrayal" thatenrages them muchmore than that of a merely (apparently) Hindu--non-Pandit--sympathizerlike myself.But like Israeli refuseniks, there is reason to believe that now India toohas its ownnay-sayers, who cannot condone the presence of the Indian armed forces inKashmir or thecontinued refusal of the Indian state to engage with Kashmiris on thequestion of azadi. Kakhimself makes the comparison to Palestine by calling the azadi movement ofthe early 90s"Kashmir’s Intifada".

What allows someone like me--born, raised andeducated in India,secular, committed to the longevity and flourishing of the Indian nation inevery sense--toget, as it were, the meaning, the reality, and the validity, of Kashmir’sagonized search forazadi? Why do I not want my army to take or keep Kashmir by force, or myfellow-citizensto enjoy their annual vacations as unthinking, insensitive tourists, winteror summer? Whydo abandoned Pandit homesteads affect me as much as charred Muslim houses,and why doI think that neither will be rebuilt and re-inhabited, nor will they be fullof life as they oncewere, unless first and foremost, the military bunkers are taken down?

The answer comes from my own history, the history of India. If ever there was apeople who ought to know what azadi is, and to value it, it is Indians. 60years ago Indiaattained its own azadi, long sought, hard fought, and bought at the price ofa terrible,irreparable Partition. My parents were born in pre-Independence India, and tothem andthose of their generation, it is possible to recall a time before azadi.

Kak’sfilm incorporatesvideo footage from the early 1990s, taken from sources he either cannot orwill not reveal.In those images of Kashmiris protesting en masse on the streets of Srinagar,funeralprocessions of popular leaders, women lamenting the dead as martyrs in thepath of azadi,terrorist training camps, the statements of torture victims about to breathetheir last and BSFoperations ending in the surrender of militants, the seething passions ofnationalism comeright at you from the screen, leaping from their context in Kashmir andconnecting back tothe mass movements of India’s long struggle against British colonialism,from 1857 to 1947.No Indian viewer, in those moments of collective and euphoric protest againstoppression, could fail to be moved, or to be reminded of how it was that wecame to havesomething close to every Indian heart: our political freedom, our status asan independentnation, in charge of our own destiny.

The irony is that azadi is notsomething we do not andcannot ever understand, but that it is something we know all about,intimately, from ourown history. What frightens us is not the alien nature of the sentiment inevery Kashmiribreast: what frightens is its familiarity, its echo of our own desire fornationhood that foundits voice, albeit after great bloodshed, six decades ago.

The British and French invented modern democracy at home, but colonized the restof the world. The Jews suffered the Holocaust, but Israel brutalizesPalestine. India blazedthe way for the decolonization of dozens of Asian and African countries, andestablisheditself as the world’s largest democracy, yet it turns away from Kashmir andits quest forfreedom, and worse, goes all out to crush the will of the Kashmiri people.Indians with aconscience--and perhaps Kak’s film will help sensitize and educate manymore, especiallythe young--ought not stand for this desecration of the very ground uponwhich ournationality rests. After all, we learnt two words together--"azadi"and "swaraj", freedom andself-rule--and on these foundations was our nation built.

We are a people who barely two generations ago not only fought for our ownfreedom--our leaders, Gandhi, Nehru, Ambedkar, and so many others, taughtthe whole ofthe colonized world how to speak the language of self-respect andsovereignty. We of allpeople should strive for a time when it will become possible for a Kashmirito offer a visitora cup of tea without rancour or irony, as a simple uncomplicated expressionof thehospitality that comes naturally to those who belong to this culture. Weshould join theKashmiris in their search for a city animated by commerce and conversation,not haunted bythe ghosts of the dead and the fled. We should support them, whether they beMuslims orHindus, in turning their grief, so visible in Kak’s courageous work ofwitnessing, into agenuine "jashn", a celebration, of a freedom that has been too long inthe coming.

Anything less would make us lesser Indians.

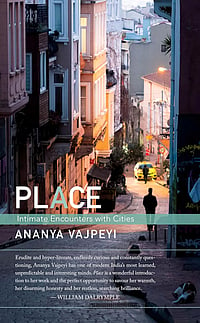

Ananya Vajpeyi is a Fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library,New Delhi (2005-2008)