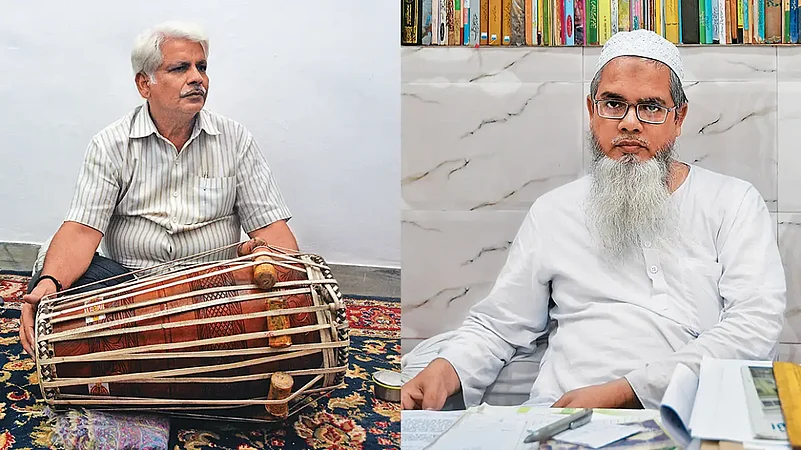

The fluorescent glow of an LED lamp washes over the little room tucked inside the premises of the Abu Hanifa mosque in Varanasi. Here, Mufti Abdul Batin Nomani spends his evenings looking at books and paperwork, while discussing theology with patrons and locals. A man of few words, Nomani does not believe human laws can be used to decide on divine matters. But since the resurgence of the Gyanvapi mosque-Shringar Gauri temple dispute between Hindus and Muslims earlier this year, legal matters are the cleric’s primary concern.

So when the Karnataka high court allowed Hindu groups to celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi inside the disputed premises of the Hubballi-Dharwad Idgah maidan on August 30, Nomani watched the news with interest. And concern.

On September 12, a Varanasi district court upheld the maintainability of a plea by five Hindu women to pray inside the contested Gyanvapi complex. Nomani, head of the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee, representing the Muslim side, says he could see the domino effect.

In May, a Varanasi court ordered a survey of the Gyanvapi premises following petitions by five Hindu women to pray inside it. The dispute grabbed national headlines with the “sensational discovery” of what the Hindu side claimed was a “Shivling” buried inside the wazookhana of the mosque. Hindus have also contended that the mosque was built after demolishing a temple, justifying the demand for permission to pray within the mosque. While the masjid committee has moved the Supreme Court against the lower court’s order, Vishva Hindu Parishad, which is supporting the Hindu side, thanked ‘Mahadev’ and said the ‘first hurdle’ has been crossed.

Soon after the Gyanvapi issue picked up steam, similar petitions were filed and old ones revived in Mathura, some 700 km away, where litigants claim the mosque had been constructed on part of a 13.37-acre plot owned by the Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust. They have demanded that the mosque land be returned to the Trust.

Nomani has faith in India’s secular Constitution. But the recent incidents in Karnataka have left him on edge. While Mathura and Kashi have been an integral part of the Hindutva imagination, Nomani feels dangerous precedents are being set every day. In Varanasi itself, there are at least two petitions filed in the court of civil judge Ravi Kishan Diwakar, seeking permission to worship the alleged “Shivling” found in the wazookhana. The Gyanvapi row has been followed by demands for the return of other mosque land to Hindus, such as the Meena mosque in Mathura.

“All I keep thinking about is the Places of Worship Act. What about that act? Does it have no meaning?” Nomani asks. The Places of Worship Act, 1991, was passed by Prime Minister P.V. Narsimha Rao’s government at the peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Section 3 of the act prohibits the conversion of any place of worship, whereas Section 4 mandates that the “religious character of a place of worship” as it existed on August 15, 1947, shall remain the same. Ram Janmabhoomi was the only exception to the act.

Nomani, who remembers the turbulent 90s very well, states that the act was brought in to protect India’s delicate communal balance following the contentious Rath Yatra culminating in the demolition of the Babri Masjid. “Even the Supreme Court, in its Ram Janmabhoomi verdict, reaffirmed the need to uphold the 1991 act,” the Mufti states.

Also Read | Will Gyanvapi Set Off Another Ayodhya In India?

Instead of quashing or dismissing petitions that violate the act, however, the past few years have seen a growing number of courts and judges allowing such petitions against mosques and other religious places to fester. This year has seen a number of hearings in three contentious property disputes, namely Gyanvapi-Shringar Gauri, Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi-Shahi Idgah and Hubballi-Dharwad Idgah maidan. Though each conflict traces its roots back several decades, they have remained outside the limelight throughout most of India’s post-independence history, dwarfed by the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

Now that the Ayodhya dispute has been settled in favour of the Hindus, the spotlight is back on the Places of Worship Act. And the act is far from being watertight.

A legal quagmire

Sub-sections 4(1) and 4(2) of the act are intended to maintain the religious character of a place of worship and prohibit its conversion from what it was on August 15, 1947, and also nullify all such petitions, with the purported reason to prevent communal tensions and majoritarian politics.

In May this year, however, the Supreme Court observed that the process to ascertain the religious character of a place is not barred under the act. It purely prohibits the conversion of the religious character.

Advocate J. Sai Deepak points out that contradictions existed in Section 4(3) of the act. Sai, who represented Lord Ayyappa in the Sabarimala case, tells Outlook that the act served to cancel itself, and was more a political strategy than a legal solution.

Sub-section (3) notes that “nothing contained in sub-section (1) and sub-section (2) shall apply to”—and names five exceptions, like when a place has been proved to be a historical or archaeological site. “The interesting thing is that while sub-section (3) cancels out sub-sections (1) and (2) that enforce the status quo, nothing cancels out sub-section (3). So the exceptions remain, even if the status quo is ruled out,” Deepak says.

He explains that under sub-section (3), for instance, anyone is allowed to prove that a place of worship is actually a historical monument, in which case the status quo stops applying. Additionally, determination of the religious character of a place is allowed, which means, “One can keep on proving that a mosque was indeed a temple”. But what happens once we have determined the character and it does not match the character of the place held in 1947? Do we convert its character, or let it be? The act does not clearly say anything. In the case of Gyanvapi, the petitioners are focused on proving the existence of a Hindu temple. But what happens if it is proved that there was a temple where the mosque now stands?

Deepak points out that instead of being a legal and secular solution to Hindu-Muslim property disputes in the religious sphere, the act creates further confusion and leaves vast room for interpretation. “The courts that are permitting pleas for surveys of mosques to look for remains of Hindu temples are not really wrong. The act allows it,” he says. “The act is either a very poorly thought-out legal solution or a very clever political move,” Deepak tells Outlook. In the end, he adds, the decision about whether the act is applicable to a place of worship, depends on the interpretation of its various sections and sub-sections.

He also adds that the exception of Ram Janmabhoomi dispute from the act, reflects that it responds more to the political climate of its time than to legal questions on matters of religious construction, belief and conversion. “Why only Ram Janmabhoomi and not Krishna’s birthplace?”

Disillusioned in the land of light

In Varanasi, the legal battle has led to myriad narratives. Some claim the temple that was demolished, was dedicated to Adi Vishweshwara and the well inside Gyanvapi—literally ‘the well of wisdom’—was created by Lord Shiva himself.

According to Hindu seer Rajeshwaranand Saraswati—a regular outside the Varanasi court where the case is being heard—the temple was built by Ahilyabai Holkar, who placed a Shivling there.

The family of mahants that takes care of the Vishwanath temple claim the temple on whose ruins the Gyanvapi mosque was built, had originally belonged to their family. While differing on political ideology, both current chief priests of the Vishwanath temple—Mahant Kulpati Tripathi and his estranged kin and former mahant, Rajinder Tripathi—agree their family had saved the shrine’s main Shivling and kept it hidden for decades, until the end of “Mughal oppression”.

Muslims claim the land on which the mosque was built was bequeathed to them via a farman by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, under whose rule the existing temple had been demolished.

Amid the confusion, many in Kashi who have seen the city shift with the turn of the tide, express anguish at the way things are going. “This is not the city I knew,” IIT-BHU professor and the mahant of Sankat Mochan temple, Vishwambar Nath Mishra, hells Outlook. “Kashi is a system, a place of spirituality. Not religion,” he says.

A pakhawaj player and music enthusiast, Nath recalled a time when he could peacefully practice at the banks of the Ganga, in solitude. These days, streaks of light from eateries and shrieks from merry-go-rounds that have opened up in the nearby Assi Ghat—the administration’s new jewels on Kashi’s ancient banks—as well as the glitzy aartis broadcast on loudspeakers, are a distraction. He chooses to practice inside his office, hoping the sound of his drum can drown the cacophony of development.

Back in the peripheries of Peeli Kothi, where the Abu Hanifa mosque is located, a community of weavers work late into the night to make saris for the city’s rich. Saifuddin, who lives in a rickety two-storey house in a lane close to the mosque, tells Outlook that all is well. “Artists can’t afford to be communal”. He elaborates that the saris he and his son make are mostly distributed by Hindu traders to shops owned by Hindus, from where they are bought by Hindu customers. But economics isn’t everything. “This is the city of Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb. It’s a way of life,” Saifuddin says. He does not care about who wins the Gyanvapi dispute. But he understands that an amicable solution between Hindus and Muslims is vital for continuing their way of life.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Domino Effect")