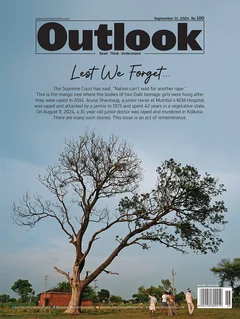

This is the cover story for Outlook's 11 September 2024 magazine issue 'Lest We Forget'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

Chronology evades Survivor H when she tries to recollect the events that altered her existence. “Perhaps, the mind’s way of recovering is to diminish painful memories.” She describes her 13-year-long marriage to a man who abused her in ways where she felt like she “died every day”. Her ordeal exemplifies the experience of being trapped and helpless in abusive marriages, which so many women undergo in the Indian society.

H says that she sensed something was deeply amiss with the man’s family from the day she met them. But her mother insisted that if the marriage didn’t take place, her father “would not survive”. When they first came to see her in Hyderabad, the family of the man examined her physical attributes; gave her a gold chain and some money; clicked her pictures; and told H’s family that their daughter now belonged to them. If H’s family broke off the wedding, they would have to face badnaami (dishonour), the man’s family declared.

A Living Nightmare

On the wedding night, when H was hesitant to consummate the marriage, her husband told her that he had an advocate ready to arrange a divorce, to scare her into submission. “When he tried coming close to me, I categorically said ‘no’. But he did not pay heed.” H tried to escape from the bedroom that night, but couldn’t.

From then on, H’s husband subjected her to relentless humiliation and torture. On their honeymoon, he told her that he wanted to exchange partners with total strangers. Any questions she asked were met with repeated assaults on her genitals. “The scars are visible when you hit someone on other parts of the body. But when you’re hit in the genitalia, you’re too ashamed to show it to anyone,” he told her during the assaults.

“My accounts of the torture were never believed,” says survivor H. Stigmatisation seems to be the primary fear that buries marital rape cases into an abyss of silence.

She recalls how warped his ideas of pleasure were—they included forcing her to watch pornography and making graphically sexual comments about her female relatives during intercourse. “Anytime I contemplated walking out, I wouldn’t be allowed. It always became a question about my family’s izzat (honour).”

“My accounts of the torture were never believed”. When H confided her woes to her relatives, they advised her to take a “positive” approach to keep the marriage from falling apart. “They said ‘this is how husbands play around in marriages’” she explains.

H alleges that during their marriage, her husband committed incest and had extramarital affairs. He also exposed her to sexual harassment from unknown men.

The repeated sexual assaults H faced resulted in the birth of her two children. She also miscarried eleven times because her husband would beat her during the pregnancies. In four of those cases, she was subjected to dilatation and curettage, a painful medical procedure to remove residual tissue from her uterus.

No Society for Women

H rues that she had no exposure to organisations that could help her with her plight. She had no opportunity to share her troubles with anyone beyond her family. The first person she was able to confide in was her doctor. Due to the repeated assaults, H had to undergo medical treatment for continuous uterine bleeding and severe infections in her genitalia.

H’s cousin was a district level judge in Hyderabad at that time; however, she received no sound legal advice even from him. Rather, he told her that he had subjected his ex-wife to similar treatment to obtain a divorce.

“I was never allowed to seek legal remedy. Even my cousin, a judge, told me that leaving would be bad for my family’s prestige and honour,” H says. She adds that women in Indian society are often raised in a cocoon and not taught the world’s ways. “We are like padhe likhe anpadh (well-educated illiterates)”.

When H sensed the looming threat of harm on her children, she decided to walk out of the marriage, never to return.

Asked whether she would have left sooner if the laws recognised marital rape as a crime, H says, “The question of legal protection becomes secondary in cases like mine. The primary issue is stigma—my family was willing to see me suffer endlessly at the hands of this brute, but not willing to support me if I walked out of this marriage. Laws alone won’t help; society’s mindset needs to change.”

Stigmatisation seems to be the primary fear that buries marital rape cases into an abyss of silence. In February this year, in Hamirpur, Uttar Pradesh, a newly-wed woman died within a few days of her nuptials. Doctors said that she had sustained injuries that they had only seen in cases of gang rapes. Reportedly, her husband, Nitil Omare, a resident of Orai in Jalaun district, consumed sex-enhancement pills before their wedding night and assaulted her. This happened on February 4; three days later, she was hospitalised in Kanpur. On February 10, a week after her wedding, she succumbed to her injuries.

According to news sources, Omare and his family neither revealed the real condition of the woman nor admitted her to a hospital. His family called up her brother and sister-in-law to complain that they had married off a sickly woman. The brother and sister-in-law had to rush her to a Kanpur hospital. Her treatment began simply for dehydration. Ultimately, the sister-in-law coaxed the woman to tell her what had gone wrong, but it was too late. At their insistence, the woman’s post mortem was conducted and her real injuries came to light.

Nine out of ten survivors refused to disclose the nature of the violence their husbands subjected them to due to fear of stigma and financial dependence on their partners.

On February 12, SI Anoop Singh of Hamirpur police station reportedly said, “We haven’t yet received a complaint in this case. When we receive one, we will begin investigation.”

Omare and his family fled their home after the woman’s death. The incident was reported across some media platforms in February. When Outlook tried to reach the victim’s sister-in-law to ask for an update on the case, she refused to speak.

Mariam Dhawale, General Secretary at All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA), is one of the petitioners in the Supreme Court challenging the marital rape exception in Section 63, Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita. AIDWA encountered similar difficulties while trying to convince survivors to become petitioners in the case.

“Survivors who came to us with their cases refused to become petitioners fearing they’d be identified and stigmatised for taking a public stand against their husbands. Some of them continue to live with their partners and their struggle for sustenance prevents them from pursuing any legal remedies,” she says.

The fifth National Family Health Survey, conducted in 2019-2020 across 28 States and eight Union Territories, says that one in three Indian women, between the ages of 18 and 49, have experienced spousal violence. At least five to six per cent of these cases are of sexual violence. The survey also highlighted “under-reporting,” with nine out of ten survivors refusing to disclose the nature of the violence their husbands subjected them to. Factors causing this inhibition included fear of stigma and financial dependence on their partners.

Women’s welfare organisations that work on violence against women cases also encounter under-reporting when it comes to spousal abuse. Jameela Nishat is a feminist poet and founder of Shaheen Women’s Resource and Welfare Association in Hyderabad. She says that it is in very few cases that survivors reveal being subjected to marital rape.

“Last year, our organisation received barely five such cases. In most situations, the survivor and her family want reconciliation with the spouse, and it is only when he does not pay heed at the level of counselling that the survivors usually consider stepping out of the marriage,” she says.

The Second Sex

At the heart of the attempts to keep such marriages intact lies the idea that a woman cannot sustain herself independently in the society.

Survivor F, 31, came to Shaheen after looking up the organisation on the internet. “When she came to us, she could barely walk or sit,” her counsellor says. F, a class 10 passout, had been working at a call centre for 12 years. But after her marriage, her husband told her that she didn’t need to work anymore.“We found him through a marriage broker. But he lied to us about being educated and employed,” she says.

F’s husband was an alcoholic who abused her daily. “He only needed a wife to have sex with, not as an equal partner. I really wanted this marriage to work, but nothing changed even after three-four sessions of mediation,” she says.

F’s husband forced her to have anal sex. When she asked to be spared while menstruating, he said, “You are deliberately bleeding,” as he forced himself upon her. F was too ashamed to share her trauma with her father and brother. The women in her family, including her mother, refused to believe her. Only after F’s counsellor revealed her plight to her mother did she stop trying to send F back to her husband. “My mother-in-law and sister-in-law used to tell me that I need to tolerate what is happening to me because he is my husband,” F says, her voice shaking with anger.

After two years, F walked out of her marriage. She received free legal aid through the counsellors at Shaheen; however, the case filed in court on her behalf is only for maintenance after separation. When asked whether she wanted to file a criminal case against the man, her counsellor says, “But how do we prove it? Who will believe her?” F has no medical evidence of her injuries as she never went to see a doctor out of the fear of being publicly shamed. “I have been advised to file criminal cases only to compel him to give me a divorce—freedom from this marriage is all that I want.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

As the Supreme Court prepares to prioritise hearing three petitions to criminalise marital rape, and the debate over it rages in the public domain, a larger battle lies beyond devising a legal framework. The primary obstacle seems to be convincing survivors that they are, in fact, survivors of rape. Apart from the lack of legal protection, overcoming the social stigma attached to reporting marital rape is one of the biggest challenges the survivors face.

(This appeared in the print as 'To Rape A Wife')