19-year-old Shree* (name changed) ran away with her partner, another young woman from the same village in West Bengal’s Howrah district, in 2020. Shree had been married to a man from her village who had grown up with her. But soon after, she realised her heart was elsewhere. “I was in love with my best friend for years. But it was much later that I realised that this was not just friendship,” she says. After six years of marriage, Shree decided to run away with her partner. She had a young son whom she left behind. Now, Shree and her partner live in a rented room in Kolkata. They work odd jobs to make a living but make sure to maintain secrecy. Shree isn’t formally divorced. She misses her child but she knows that society won’t accept her relationship with a woman. If I return, they won’t let me leave,” she says, referring to her family and in-laws.

Shree is one among thousands of other queer persons in India who face discrimination, hardships and even violence for expressing their sexual orientation and gender identity. These issues, faced by members of the LGBTQIA community, do not usually get covered by the ambit of family laws. Yet the queer community is often directly affected by laws around marriage, inheritance, custody and adoption of children, which are under the purview of personal laws.

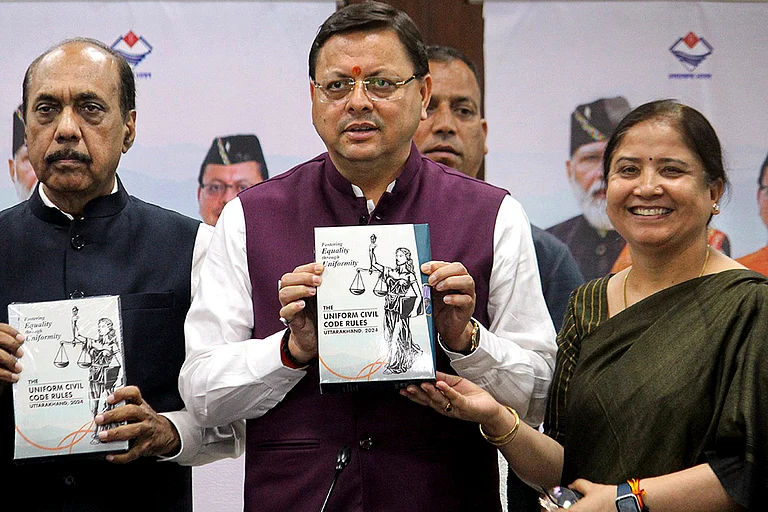

With the debates over the Uniform Civil Code (UCC)—a pet project of the BJP for years—gaining steam in the run up to the 2024 General Elections, critics have been questioning the validity of the claim. The Indian government’s penchant for the UCC has been propped on the assertion that replacing family laws would bring about empowerment for women. In other words, it has been pitched as feminist legal reform. A closer look at the UCC in its current form and the discourse around it, however, reveals that though purportedly feminist, the reform seems to ignore sexual minorities including lesbians and trans-women.

“Queer marriage itself is still taboo in India, legally as well as socially. So a UCC alone is not going to resolve many key issues that the queer community faces,” says Sophia Rajkumari, lawyer and queer legal expert from Imphal, Manipur. “For many in the queer community, it is still a fight for identity. In such a situation, it is hard to see how a UCC will have a positive impact on the queer community,” she adds.

If implemented thoughtfully, the UCC may open up ways for the LGBTQIA community to live dignified lives.

It is not just the right to marriage that is denied to queer couples but also the right to adoption and custody of children which remain contested questions for the community. In 2019, the government had passed the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill which denied live-in and same-sex couples permission to commissioning surrogates.

Moreover, trans activist Grace Banu adds that there are at present no guidelines in the UCC relevant to the queer community. In July 2018, members of feminist queer organisation wrote to the Law Commission of India with suggestions on family laws and seeking guidelines for the community within the UCC framework. One such suggestion included the request for the commission to issue guidelines for people to register their legal representatives through affidavits or other methods which are accessible and easy to execute with a standard format to streamline the process of inheritance among LGBT communities. “No such guidelines have been provided,” Banu states.

In terms of transgender rights, Banu argues that before demanding for a UCC, the trans community needs to focus on seeking separate horizontal reservations. “Reservations will bring empowerment, and allow minorities like the trans community to enter spaces of discourse and impact policies like the UCC, she states. “Without reservation, we won’t be able to call the nation or its institutions truly diverse,” she adds, suggesting that reservations will allow for more transgender people to

access education and employment.

However, marriage equality for transgender people is still a distant dream. “Despite the NALSA verdict and decriminalisation of Section 377, the trans community in India has very few rights and continue to remain invisible,” says Vyjyanti Vasanta Mogli, trans activist and one of the petitioners for marriage equality in the Supreme Court represented by Advocate Jaina Kothari. She states that at the moment, even marriage equality seems unattainable. “Marriage is essentially part of civil code, it isn’t part of criminal procedures. But it is absurd that many of the ones who are so vociferously resisting marriage equality are also the ones pushing for UCC,” she states. “We await the verdict. Until then, it’s hard to say if the UCC will have any impact on the LGBTQIA community,” Mogli states.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

At present, if implemented thoughtfully and is inclusive of gender and sexual minorities, the UCC may open up ways for the LGBTQIA community to live dignified lives. But members of the community feel that the UCC does not directly make them a priority. “It just shows that no government actually cares about the LGBTQIA community’s needs. In its present iteration, UCC is likely to only benefit some Savarna women,” says Banu.