Nothing could have been more brutal and bestial than a pregnant woman being gang-raped in front of her mother and the mother in front of her. Nothing could have been more gruesome and barbaric than to have the same woman witness a mass murder of 14 members of her family. Bilkis Bano, a Pasmanda Muslim, however, escaped death and survived to fight for justice. The Bombay high court upheld the conviction of 11 accused to life imprisonment on the charge of gang rape and murder and this year the convicts completed more than 15 years in jail.

On August 15 this year, Independence Day turned out to be a ‘horrendous day’ for Bilkis when the Gujarat government prematurely released all the perpetrators of the heinous crime from prison. The government chose to follow the retrospective Gujarat remission policy of 1992, despite having a more progressive existing remission policy of 2014, which was made post-Nirbhaya case. Shocked and horrified at the release of her rapists and murderers of her family, Bilkis and her husband started looking for a safe house.

Why remission?

The post-remission scenario appeared as a ghastly spectacle on our TV sets. The rapists and murderers, after their discharge, were welcomed by their women family members, who garlanded them and applied tilak (a pious mark) on their foreheads. Thereafter, a disturbing commentary made the rounds that the rapists belonging to the virtuous caste and kinship would not have committed the crime. Implicit in this narrative was the rhetoric that Bilkis is lying and, therefore, immoral and that there has been miscarriage of justice. But the question in the first instance is why such remission was exercised by the state government.

The idea of remission in criminal jurisprudence, taking into account the nature of crime, is the cancellation of part of the prison sentence generally for good conduct. The power of remission, referred to as a prerogative of the executive, is exercised largely based on subjective satisfaction. The question is: should the executive enjoy such discretionary power, when the decisions about remission reflect intuitions rather than the facts and ethics of the circumstances? If the discretionary power of remission is exercised with impunity and discrimination, the purpose of prison and the state being benevolent and reformist is defeated. It is important for the government to use ‘application of mind and reason’ and understand ‘justice as fairness’, while considering individual cases for remission. In the Bilkis Bano case, there is an error of judgment on the part of the executive to understand the seriousness of ‘differential principles of criminal liability’ in cases of gang rape and sexual violence against women. Remissions for the convicts of gang rape or, for that matter, any kind of rape, hollow out the laws and criminal jurisprudence system. The appalling spectacle post-remission of the 11 convicts in her case was an effort to trivialise rape and project it as part of a larger mass crime during the Gujarat pogrom of 2002.

Understanding rape

Most feminist scholars agree that rape is universal and takes particularistic characteristics in specific cultural settings. In her pathbreaking book Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975), Susan Brownmiller describes rape as an act of forcing a woman to have sexual intercourse, despite her resistance, and, therefore, the continuous sustenance of male domination over women by force, which is indeed the public secret of patriarchy. During war, or communal violence, a woman is raped because she is seen as an ‘enemy’ to be conquered by any means, and the foes, therefore, must lose their land, goods and women. This was carried out as a matter of normal revenge policy by the Nazis, the Allied forces in World War II, the American soldiers in Vietnam or during communal and mass violence in the post-Partition India. Then there is everyday rape, some reported, some unreported. In India, about 90 rapes are reported every day.

Unexplained volte-face

The Supreme Court sought responses, including all the information and relevant records pertaining to the remission and the Bilkis case per se, on a petition challenging it. The apex court categorically clarified that it did not ever grant any sort of permission for remission of the convicts and its suggestion to consider the remission in terms of the policy applicable in the state where the crime is committed should be construed only as taking up the case. However, the moot question is when the Supreme Court itself shifted trials to Maharashtra due to lack of faith in the judiciary of the state and the possibility of the state government influencing the trials in Gujarat, why did the apex court direct the state government to consider the plea and that too as per Gujarat’s 1992 remission policy within a short span of two months?

The implementation of the retrospective remission policy in the Bilkis case does not augur well, because the chilling impact of remission on Bilkis and other women in India is prospective and not retrospective.

The robust mass protests, as in the Nirbhaya case, were missing against the remission in the Bilkis case. From Nirbhaya to Bilkis, feminist movements against rape and sexual violence against women have gone weak. We witnessed a couple of protests in a couple of cities for a couple of days, but much to the chagrin of civil society, they died down. Feminists belonging to left-liberal, majorly left, ideology protested and demanded that the apex court rescind the remission. Where are the other feminists, particularly the right-wing feminists? Don’t they see Bilkis’s case as women’s case? Conservative feminism, so to say, is an oxymoron because feminism essentially is an ideology that challenges the conservative and traditional mores and codes embedded in patriarchy that enslave both women and men.

The way forward

The Bilkis case trial is unique in the sense that it dared to bring mass sexual crimes into the judicial discourse, which rape cultures had otherwise made ineligible for legal discussions. It is time to think about the enormity of the burden and courage that rape survivors carry. Perhaps, keeping Bilkis in mind, it is imperative to ask some hard questions about the deeper causes of rape and sexual violence against women and the inability of the law to remedy the situation. Perhaps, it is time to resolve the perennial differences in women’s groups and build an alliance to resist the widespread impunity that the perpetrators of rape enjoy. And also, it is time to talk about and create a knowledge base as to why some cases of rape go unreported.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Travesty Of Justice")

(Views expressed are personal)

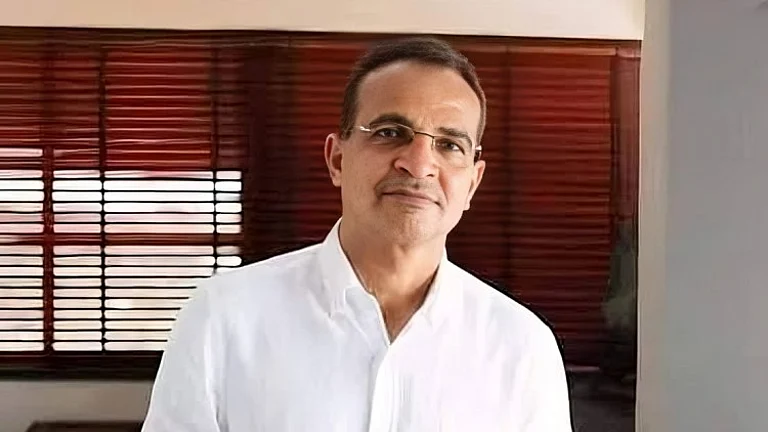

Tanvir Aeijaz teaches public policy at DU and is Director (hony) at the Centre for Multilevel Federalism, New Delhi