“When did you learn to cook, when you were young?” asks Rahul Gandhi.

“Yes, I was young. In 6th or 7th standard,” former Bihar Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav replies. “I had gone to Patna where my brothers were working and I used to cook for them.”

This brief exchange of culinary queries on August 4 this year between Gandhi, a political scion and one of the most controversial politicians of his era, Yadav, appeared an unusual one as both opposition politicians, prime movers of the INDIA alliance, lounged on patio furniture, waiting for the meaty contents of a thick aluminium pot to sizzle just right.

Gandhi and Yadav seemed deeply engrossed in their ‘Chat over Champaran Mutton’ at Yadav’s daughter Misa Bharti’s Delhi home, a departure from the popular ‘Chai pe Charcha’ discussions before the 2014 elections.

The choice of Champaran mutton may seem a far cry from the exotic foxtail millet leaf crisp chaat, jackfruit galette and glazed forest mushrooms served at the ‘all veg’ dinner for world leaders at the recently concluded G-20 event in New Delhi.

But Champaran mutton seems to be a deliberate choice opted by the opposition politicians, given the temperament of vegetarianism the ruling party has been fostering with abandon.

Could it be that the slow-cooked rustic lamb delicacy, associated with the Champaran region of Bihar, was an attempt by Gandhi and Yadav to invoke not just the spirit of liberalism, but also regionalism while cleverly forging a subliminal Gandhian connect? Mahatma Gandhi started his first Satyagraha movement in 1917 from Champaran against tyrannical British rule. Is Champaran mutton now being pitched as a symbol of secularism, of inclusion, both key planks of the INDIA alliance?

Promoting meat-eating on a national platform is bold in today’s political climate, even for Lalu Prasad Yadav who has forever maintained a rustic, people’s leader image. Once a ‘strongman’ known for his wit as well as a litany of corruption-related controversies, Lalu is considered by many to be an advocate of secularism and has in the past successfully channelled the M-Y (Muslim-Yadav) formula to help his Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) win successive state elections in Bihar.

On August 4 however, Yadav, who immortalised the no-holds-barred Bihar style of politics in the national capital, said that he had brought along the raw mutton from Bihar to Misa’s house in Delhi, so that he could cook it specially for Gandhi.

In an era when many male politicians in India embrace hyper-masculinity and weaponised celibacy, this video, with over three million views, presents a different political creed, which suggests that Gandhi is at ease with ‘feminine’ tasks like cooking and represents a secular, non-vegetarian, liberal and feminist perspective.

Though ostensibly organic, the video is hardly a coincidence. It was released on YouTube on September 2, shortly after the third meeting of the India National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), a joint alliance of 28 Opposition parties led by Gandhi’s Indian National Congress, which includes Yadav’s RJD, tasked with countering the BJP in the crucial 2024 general elections.

“I see it as a political strategy to construct an oppositional framing to the hypermasculine figuration of Modi—one that is historically tethered to Gandhian ideals of non-violence, liberalism and secularism. It is a competing alternative to Modi’s figuration,” says researcher Amrita De, who studies masculinities and feminist theory at the State University of New York at Binghamton.

But will this image engineering work in favour of the Opposition? To answer that, one must first understand why and how Modi’s brand of masculinity works at present as the dominant integrator of masculine identity, especially in the digital age.

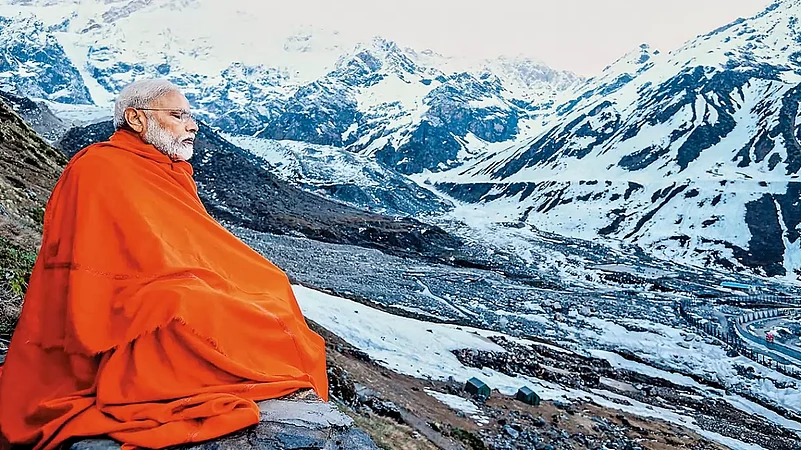

De explains that a majority of the semiotics of this social media branding are focused on projecting the image of Modi as “decisive and unflinching, inflected with a brash aspirational machismo.”

“The theatrical semiotics of his political campaign on social media engendered a brand of populist politics, uniformly integrating disparate public cultures underlined by class caste intonations into a singular ideological construction,” said De, who has authored a paper titled ‘Masculinities in Digital India. Trolls and Mediated Affect.’ “This discursive branding of him as an ideal leader is initiated through an innovative mix of Hindutva protectionism and developmental rhetoric.”

He has also successfully framed himself as the deliverer from Congress party’s corruption through the projection of the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign, announcing himself as the ultimate mascot of vikas or development for neoliberal India, De argues.

IIT-Madras Professor and author of ‘The Developmental Desire: The Crucible of Masculinity, from Nehru to Modi’, Jyotirmaya Tripathy feels that despite his overt displays, Modi remains an ‘enigma’ that needs further time to decode. “We don’t have the template yet that can reconcile opposites that Modi symbolises: both aggressive and accommodative, unabashedly masculine and subtly feminine, culturally right wing and economically feminine (to a large extent),” Tripathy adds.

The duality is reflected in his celibacy, a symbol of sincerity and selflessness in politics. Anthropologist Joseph Alter posits virility through self-control, prioritising public good over power-seeking strategies. “So, it’s exercising self-control in order to become powerful in a way that is not self-interested. At least the ideal of the philosophy is precisely that,” Alter states.

But is there really a measure to gauge ‘sincerity’?

The concept of hyper-masculine celibacy also reveals a duality within masculinity and underscores the complexity of this notion of manhood.

According to Tripathy, there is no inherent concept of masculinity; it’s a matter of perceiving traits or associations as masculine, a notion termed discursive construction in academia. He notes that the demeanour projected by PM Modi is assertive, questioning whether a figure like Jawaharlal Nehru would find acceptance as prime minister today. Tripathy speculates that Nehru’s pacifist approach and Anglophilia might not align with modern India’s aspirations, but his intellectual agility would endure, positioning him as a philosopher and thought leader in any era.

Gautham Machaiah, a Karnataka-based political analyst, emphasises that in such matters public relations and branding trumps masculinity itself. Leaders like Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, V P Singh, Charan Singh, H D Deve Gowda, and A B Vajpayee all strategically shaped their public images. However, in the digital age, leaders like Narendra Modi have their personas meticulously curated by PR agencies and online influencers, unlike in the past, he argues.

So, can similar branding and PR strategies around the construction of an alternate brand of masculinity work for Rahul Gandhi as well? After all, the Congress seems to be attempting his image makeover. From monikers like Pappu which are subversively rooted in projections of ‘failed’ masculinity, Congress’ and perhaps Gandhi’s own strategy is to pitch him as a liberal, Gandhian, almost ascetic bulwark of secularism and federalism.

From drinking Mohabbat ka Sharbat in Old Delhi to his vocal speeches in foreign universities and bike-borne road trips to Ladakh, Gandhi has managed to keep the cameras on him. However, analysts like Machaiah and Tripathy feel that despite his seemingly genuine intentions, Rahul Gandhi’s brand is still far from competing with Modi’s populism. “Gandhi’s branding is still confusing. You may like it or not but you know what Modi stands for. He stands for Hindus and for aggressive majoritarian politics. But what does Rahul stand for? Secularism? Feminism? Metrosexuality? Farmer’s rights? It’s not yet clear,” Machaiah states.

Machaiah notes that perceptions of masculinity depend on context, citing Manmohan Singh’s ‘weak’ image despite leading economic and nuclear reforms. He attributes this to Congress’s failure to promote Singh’s achievements, similar to Rahul Gandhi’s struggle with his successful Bharat Jodo Yatra.

Beyond the realm of constructed branding, Amrita De feels that the support Modi’s brand of masculinity gets in India is both constructed and organic. “There is definitely an affective restructuring propelled by Modi’s branding through digital mediation, which solidifies a sense of muscular nationalism, which is then disseminated with the goal of mass consumption,” she says.

De asserts that there isn’t a distinct starting point for this influence, but it originates from past Islamophobia, forming a generational base that backs Hindutva and presently, digital platforms amplify this effect.

The machismo in religious majoritarianism brings us back to the story of Gandhi and Yadav’s Champaran mutton. Can it become the unassuming face of an attempted shift toward a more secular, inclusive leadership?

Over the past few years, meat-eating or suspicion of cow slaughter for consumption has led to several incidents of lynching of minorities like in the case of Uttar Pradesh’s Mohammad Akhlaq in Dadri in 2015. Later investigations revealed that the meat in his house was, incidentally, mutton.

In India, where food has always been deeply political, is the INDIA alliance hoping to use Champaran mutton in the same way as Mahatma Gandhi tapped salt during the Dandi March? And, can this expensive non-vegetarian delicacy manage to emulate the national appeal of the more ubiquitous and humble salt? Perhaps we should let INDIA’s cooks stew in that dilemma for a bit.

(This appeared in the print as 'Macho vs Metrosexual')