The recent judgement of the Supreme Court of India on sub-categorisation in the reservation category of the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes is beyond comprehension. The Constitution of India does not recognise ‘‘a caste’’ but the group of castes, and hence, the judgement is against the constitutional mandate. Besides, the idea of representation gets completely demolished under such bifurcations as its methodology is deeply problematic in the light of diversity. The assumption about over- and under-representation has no empirical data, consequently, everything is based on imagined ideas and presuppositions. As has been pointed out by many that the communities who gave up their traditional caste occupation and opted for education are the ones who are employed in government services.

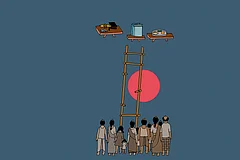

In the recent Parliament session, Member of Parliament Chandrashekhar Azad submitted that only two per cent jobs are in the government sector and the rest are in the private sector. This shows that the government sector provides only a small pool of jobs whereas the large pool of employment is in the private sector, which has no reservations. However, such a glaring reality does not become an issue; and the concept of reservation in private sector employment is neither demanded or even thought about. The worst part is, similar such bifurcation on the basis of under- or over-representation is not considered in the claimed open as well as the Economically Weaker Section (EWS) category. The open category too should go under such methodological deliberations as for the fact that how every time subversions are created constantly would become a reality in the public domain.

Perception about under- and over-representation of the communities within the ambit of quota reservation of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes is a matter of cultural misnomer propagated due to vocal visibility of certain groups/castes that has become part of the cultural syndrome of the caste-Hindu communities, which would not like to accept the idea of representation as part of constitutional democracy. Such cultural thinking is a matter of no concern as it helps to safeguard the interests of the dominant section. It eventually created a norm/standard of caste-Hinduness that gets legitimised every now and then.

Cultural syndromes are constantly protected by the governments in power. Take the example of nomenclature ‘‘Hindustan’’, which is regularly invoked as the name of the country in public and in Parliament debates and discussions. The Constitution says that the name of the country is “India i.e. Bharat”. But the leadership hardly has any sense of realisation, including those who flash the Constitution and keep on saying ‘‘Hindustan’’, which itself is unconstitutional. This becomes a huge syndrome to inculcate a process of nation building in the light of what was, what it is today, and what it will be in the future. The majority is a syndrome that overpowers everything as a part of the political and social syndrome, however, it is the hegemonic caste-Hindus who in reality are a numerical minority and act as the dominating force that defines public perceptions as well as the functioning of the State. Thus, there is no unbiased thinking that becomes a goal or a desired ideal.

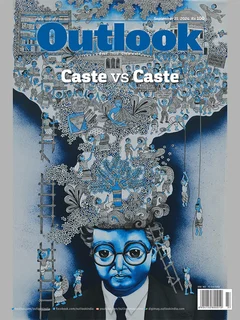

The claims of modernity in the social and cultural spheres are a matter of public perceptions and claims. Such claims are now being questioned by the ideas of “Ambedkarian aesthetics”, which I define as follows: The term ‘‘Ambedkarian aesthetics’’ is a world free from prejudices, inhibitions and metanarratives of hegemonic/Brahminic modernity. Its historical trajectory is to subvert the narrative of the ‘‘given’’ and propose to get into a process of dismantling inhibitions that have been nurtured over a period of time. The historical past, both ancient and modern, are constant reminders of ideas of contradictions that have been part of lives, including the life of works of art. For many, it is a constant engagement to kill ‘‘protected ignorance’’. Modernity in India is a Brahminic modernity that never allowed Indian citizens to become unbiased. Their functioning itself is one such thick-skin syndrome that is not addressed as a problem.

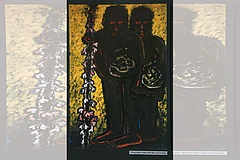

Expressive capacities from the margins have raised the question of the nature of language itself. This is very well articulated through Dalit literature. It forced to dismantle the canonised idea of language. Similarly, in the creative visual world, the symbols used by Ambedkarian thinking are often not entertained or accepted by the dominant caste-Hindu groups. Their perception is ruled by transcendental ideas. On the other hand, such transcendental aesthetic pursuits are questioned and challenged by the aesthetical thinking as resolved through the Constitution of India. This has always created discomfort among many syndromist caste-Hindu groups and thinking that is largely governed by the vedantic thinking. The idea of sub-classification is not a matter of concern, on the contrary, the material basis of the community is largely liberating elements in their creative expressions and have enriched the cultural practices.

There are young creative minds who have excavated the history of their communities and are making use of the material that was part of community practices. Such community material practices have become part of material traditions and vibrancy in the actual making of artworks. Nevertheless, as and when their ideas are generated through the Ambedkarian thinking, there is an immediate reactive behaviour, thus, the true nature of a vedantic syndrome comes like an apparition. The sub-classifications are no criteria, but the nature of patronage extended to such artists is minuscule and does not go on to become the norm. Saleable quality and their material means have become one important ‘‘syndrome’’ of promotions, but the germination of ideas behind the artworks has become a matter of ghettoised safe-guarded domain that will not allow to change perceptions. There is no rational self in the process but an accepted norm of presuppositions involved in the politics of judgement in the creative realms.

Any ideas reflective through material practices that question the syndromes of caste-Hinduness are collectively fought and a sense of rejection is created among the dominant groups of society that eventually produce cultural margin. India celebrates Teachers’ Day on the birth anniversary of a person who allegedly published his own student’s PhD thesis in his name. The then government in power suddenly forced the idea that his birth anniversary be celebrated as Teachers’ Day. No one has undertaken a public deliberation on this. There is neither a rethinking on such celebrations nor any rational investigations. It is converted into a convention and a norm. This norm is created and imposed by the syndrome of Brahminical cultural nationalism that constantly promotes a culture of psychotic senselessness.

Consciousness is key for any transformation. Consciousness in India is largely a consciousness of senselessness. No material means can change the consciousness of senselessness. Realisation of upward mobility among the social and community groups of the touchable communities is that of going towards caste-Hinduness (savarnatva), not equality. It’s a syndrome that keeps subverting the constitutional ideals. Therefore, being democratic and modern become mere claims by the majority of the population that remains irrational. The newly constructed landscapes of architectural designs are a part of modernity, but the demographic-hidden caste-Hinduness (savarna) promotions are not realised through such mechanisms. The minorities are forced to become part of cultural syndromes that produce fear, terror and subjugation.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Y S Alone The Writer is Professor, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi

(This appeared in the print as 'syndromic promotions')