Ever since her husband’s death, the middle-aged widow of Shamlu ‘Bama’ Kohrami lives in fear for her young children’s lives. Kohrami had gone searching for his lost oxen in Keshkutul village, located in the Naxal-inhabited Bijapur district in Bastar, Chhattisgarh, in July this year. He was allegedly killed in an encounter with the police.

“They claimed he was a Maoist. But he was just a farmer,” she insists. The widow has demanded compensation and written assurances from the government and local leaders, formally guaranteeing that her children will not be falsely labelled as Maoists and killed. Against hopes that her demands would be heard during the 2023 Chhattisgarh Assembly elections, Shamlu’s widow, Nande Kohrami, was shunned by politicians. Her village, part of the “Maoist belt”, felt neglected despite the electoral process.

Bastar, where elections usually take place in the crosshairs of violence between security forces and Maoists, has seen an increase in the number of polling stations in “sensitive” areas this year and some districts like Dantewada have recorded a slight increase in voting percentage. The mood in Bijapur, which recorded the lowest voter turnout, nevertheless remains tense. While state and security forces’ narratives blame the “Maoist boycott” of elections for the low voter turnout, the region has seen a steady flow of anti-government protests led by unarmed Adivasi villagers for nearly two years now.

Jal Jangal Jameen

Twenty-one-year-old Vinesh Kumar Podiyam from Rekawa village at the Bijapur-Narayanpur border feels that elections in Bastar are not a celebration of democracy. “They say that India became independent in 1947, but we Adivasis are not yet free,” he says.

Podiyam is a member of the Adivasi Moolvasi Manch, which has been waging a democratic war against what he describes as “anti-tribal development”.

Adivasis, he says, are fighting for jal jangal jameen, opposing the construction of six bridges across the Indravati River in Bastar. Built without consultation, locals argue the bridges aim to enhance mining connectivity.

“Adivasis cannot access these roads. They (CRPF) notice when we come to markets to buy supplies. They target us when they think we are carrying a lot of goods into the forest. They claim we are carrying it for Maoists. They do fake encounters or put us in jail without cause or hearing where we are tortured until many die. Is that freedom?” Podiyam asks.

In 1910, tribal leader Goonda Dhur of Jagdalpur (today an urban centre) led the Dhurwas of Kanger forests in Bastar to battle against the British, marking the first fight for jal jangal jameen in the region. Today, Adivasis in Bastar continue to struggle, facing state repression.

In March last year, the Moolvasi Manch staged a peaceful dharna against the alleged exploitative development in Bijapur. On March 26, security forces lathi-charged and arrested eight organisers, detaining them for three months.

“About 50 people in the crowd were grievously hurt in that incident. We lost much in terms of supplies, including food and medicines,” Podiyam recalls. That lathi-charge put a halt to the protests, which gained strength again in 2023. “We were demonstrating until June this year and we plan to resume once the election season is over,” says 19-year-old Sunita Tamo from Belnar village. Sunita is a member of the Mahila Adhikar Manch, a sister body of the Manch that works specifically on Adivasi women’s issues. Belnar and scores of other villages Outlook visited in Bastar did not have taps at home, electricity or steady drinking water supply.

In 2021, Adivasis, including Tamo, Podiyam and thousands of others, protested in Silger against the setting up of an army camp on their land, before being lathi-charged. Alleged firing by security forces resulted in three deaths. Ongoing resistance in Sukma, Bijapur and Dantewada follows protests against “development” and fake encounters, leading hundreds, including Tamo and Podiyam, to abstain from voting.

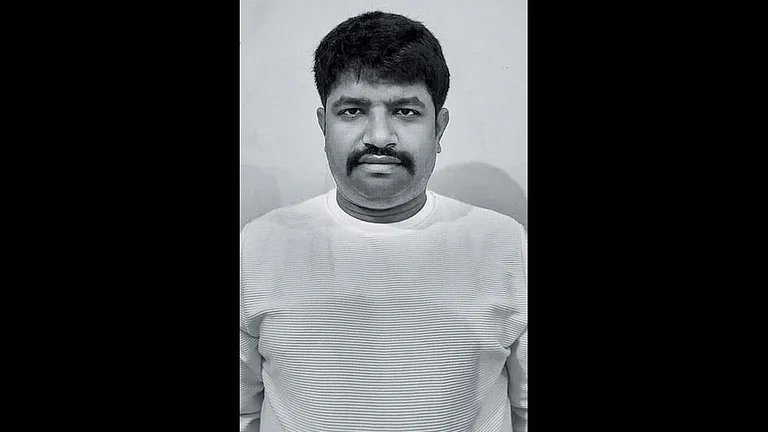

Locking up or “encountering” innocent Adivasis when they question governance or police brutality is a familiar tactic for security forces in Bastar, explains Adivasi activist Rajendra Kadti. “When tribals ask for their rights, the police call them “Naxal” and lock them up on fake charges. They beat the villagers with sticks. They don’t behave this way when the media is around,” says Kadti, a member of Sarva Adivasi Samaj.

Across the Indravati

Despite the real and perceived threat of “left-wing extremism”, Adivasis in Bastar share a dual relationship with Maoists, who sometimes act as guardians of Adivasi rights against exploitative punjiwaad (capitalism). But they are also quick to often kill innocent Adivasis, suspected of being police informants.

The Maoist movement in Bastar gained momentum from the 1980s, evolving from the People’s War Group, India’s first Naxal faction. By 2004, it merged into the Communist Party of India (Maoist), now controlling vast forest and hill regions in Dandarkaranya. Until the early 2000s, Maoists were figures of legend, but their impact escalated with the formation of Salwa Judum in 2004-05, leading to significant bloodshed, according to Mangal Kunjam, a Bijapur-based scribe and member of the Sanyukta Panchayat Jansangharsh Samiti, a body of village headmen in the Bailladilla region.

Salwa Judum, active between 2005 and 2007, comprised armed vigilantes terrorising rural tribal areas in a purported anti-Maoist effort. Its members were accused of killing innocents, raping women and destroying villages in the name of counter-terrorism. “If they suspected one person of being a Maoist, they would kill the entire family, even babies,” Kunjam and Kadti recall. Because of their terror, Adivasis turned to Maoists in large numbers and joined their cadre. One such man from the Bailladilla region, where Kunjam grew up, was Badru. But more on him later.

“Their (Maoists) recruitment strategy was interesting. They started with educating us about our rights and our history,” Kunjam says. Original owners of the land and crucial in the anti-colonial fight, the histories of the Adivasis, like the one featuring Goonda Dhur, are lost in modern India.

“Growing up, we didn’t know who our ancestors were or what they did. We didn’t know that the forest belonged to the Adivasis. The Maoists taught us our own history, something the government should have done, not an armed militia,” he says. Maoists, for instance, started celebrating the shaheed jayantis of tribal leaders like Goonda Dhur, Gain Singh and Birsa Munda. These celebrations were dubbed “Maoist-backed” events by state agencies.

Schisms within Adivasi identity were exploited by Hindu groups campaigning in the region to bring Adivasis back into the Hindu fold. Mukhiyas (headmen) and landlords were some of the first to join forces with them. They were, in return, recognised as “dwij” or twice-born Brahmins.

Mahendra Karma, former Congress MLA from Dantewada and founder of Salwa Judum, was among the first such converts. In 2005, with the coming of the BJP government in Chhattisgarh, the communal divide amongst tribals sharpened. Kunjam and thousands of other Adivasis chose or were forced to move out of their ancestral villages in the Abujmarh region across the river with Salwa Judum members to temporary relief camps. Those who refused to move were killed after being branded as “Maoists”.

To convince people to move, the government as well as the security forces assured the villagers of government jobs, cushy homes and cash rewards. A majority of the tribals who made the move, eventually got nothing.

Kasoli village in Dantewada is home to hundreds of families that relocated from Abujmarh with hopes of rehabilitation and a better life. Nearly 15 years on, the families continue to stay in those camps, which have mushroomed into villages. No jobs came their way, nor has any form of rehabilitation. The immigrants remain at the edge of town and forest, shunned by both the government and the Maoists. “We don’t even get 100 days of work under MNREGA,” states Jai Ram, who moved to Kasoli from Neeram in 2005, when he was just a child.

His six-month-old daughter, Nayantara, gurgles in his lap as the sun sets. Ram longs to return to his village. “In the forest, I could have raised her for free. There is food to grow and water to drink. In the basti (urban slum), we have to pay for everything and we don’t have any money,” he says.

While the Maoists showed the Adivasis the path of protest, the tribals today feel that their community has been led astray by both the government and the Maoists. “Since 2013, nearly 1,000 top and mid-level Maoist leaders have done atmasamarpan (surrender). They became decorated members of the security forces and helped them hunt for Maoists. Villagers find it very hypocritical,” Kunjam states. People like Badru, he says, who had enthusiastically preached the jal jangal jameen ideals two decades ago, are now parading with the CRPF.

Adivasi Politics Taking An Independent Turn?

Efforts to build a social and political entity among Adivasis have a long history. In Bastar, new outfits specifically batting for tribal interests have emerged. Former Congress leader and cabinet minister Arvind Netam has floated the Hamar Raj Party to challenge the Congress and the BJP’s politics of appropriation.

“This is the first attempt to formally consolidate tribals as a political entity in Chhattisgarh. It is important to start somewhere,” he states. More than ever before, says Netam, Adivasi factions need to unite and fight against the anti-tribal and Brahmanical policies of the central and state governments.

“Neither the Congress nor the BJP will ever pass the baton on to an Adivasi. We have to fight our own battles,” he told Outlook. Hamar Raj Party’s Bijapur candidate, Ashok Telandi, says that if elected, he will work to implement the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act and renegotiate development plans in the region after consulting locals and gram sabhas.

Locals, ironically, seem to have no faith in the party, with a majority leaning towards the region’s other political bigwigs. Sarva Adivasi Samaj (SAS), the parent civil body from which the Hamar Raj Party was born, too, has distanced itself from Netam’s outfit.

“Relentless work by civil society organisations has led to the creation of a certain level of empowerment and self-awareness among rural Adivasis. Suddenly making it all about elections confuses the populace and dilutes the work done by civil society as it pits tribals against each other,” says SAS Bhairamgarh block president Sitaram Manjhi. He explains that every party, including the BJP, the Congress, the CPI and others, has fielded Adivasi leaders as election candidates. Adding more leaders to the fray just creates further division in the “samaj”, he says.

“Unity is important for the Adivasis to realise their goals. But by creating new parties, this unity is being divided and the movement is suffering,” he says. Another SAS member, Sunil Ursa, adds that the party is too young and locals view it suspiciously. Many think that it will not be efficient at developmental work, while others feel it may act as a “vote cutter” and against the interests of deserving candidates.

“It’s not like the party is going to get a full majority and form a government that truly represents Adivasis. Eventually, it will join some bigger party and become a slave to some industrialist or the other,” Ursa says.

Locals in Bastar prefer Netam’s party to work first at the grassroots with Panchayat elections, progressing to Zilla Panchayat, cultivating a voter base before targeting the assembly polls, emphasising on strategic groundwork.

But trouble has been brewing for some time, especially on the religious front in Bastar. Fissures have appeared among Adivasis practicing the indigenous religion, Hindu Adivasis and Christian Adivasis. At present, the 12 seats in Bastar (11 of which are reserved for ST) are under Congress rule. The BJP, however, is expected to do well in seats like Narayanpur, where the party has been accused of supporting communal and anti-tribal Christian narratives. The saffron party seems to have the support of both Hindu as well as non-Hindu, non-Christian tribals. Many in Dantewada as well as Bijapur also dubbed “excessive proselytising” by Christian pastors and church groups as a “threat” to the indigenous Adivasi culture.

Historically, political forces have exploited such perceived threats to weaponise Adivasis against their own. The Adivasi response to communalisation during this pivotal Bastar election, where the BJP appears to be creeping to victory in some seats, will define the trajectory of their political assertion in Chhattisgarh’s future.

(This appeared in the print as 'Inheritence of Loss')

Rakhi Bose and Raunak Shivhare in Bastar