In 2013, a group of about 10 people in their early 30s, who viewed cinema as a medium of developing political dialogue, came together to form the People’s Film Collective (PFC). Their idea was to take documentaries on socio-political issues in different Indian languages to the common people these films talked about.

The first such film screening took place at the closed Gouripur jute mill at Naihati in North 24-Parganas district, where an agitation by retired workers was taking place. These workers had not received their provident fund, gratuity, and pension payments for 16 years. Under a makeshift tent just outside the gate of the closed mill, PFC screened Anand Patwardhan’s Occupation: Mill Worker, a 1996 short documentary on Mumbai’s textile mill workers, and Gadi Lohardaga Mail, a documentary from Jharkhand on the memoirs of a narrow-gauge rail line. The event also screened a campaign video on Gouripur mill workers’ struggle.

The public reception to the screening session and the interaction that followed convinced the group that more such screening events were required. “We want to communicate with people, politically through cinema. The interactions that take place after a film screening matter the most. Films raise different questions and give people something to think about,” says Kasturi Basu, a science researcher, documentary filmmaker and a founding member of PFC.

Basu recalls that a parallel film society movement, focusing on non-fiction, had started taking shape in different parts of India from the first decade of the new century. There’s Pedestrian Pictures in Bengaluru, Vikalp in Mumbai, Marupakkam in Chennai, Samadrusti in Bhubaneswar, and Akhra in Ranchi. Calcutta’s strong film culture of the 1950s and 1960s that focused on fiction, died down by the 1980s, and no such initiative of documentaries ever consolidated. “We felt a vacuum in West Bengal. So many documentaries and short films were being made across India, but such screenings do not get space in theatres, TV channels and digital platforms. Moreover, the underprivileged hardly have access to these platforms,” says Basu.

This realisation led the group to create a bridge between the underprivileged and the films that provoke people to think independently. One of the subsequent screenings took place among construction workers at Bandel area in Hooghly district, where a worker had lost one of his legs in an accident and other workers were raising funds for his treatment. Among the films screened was Patwardhan’s 1985 documentary, Hamara Shahar (Bombay: Our City) that included comments on the lives of construction workers. “While screening such films among the working class, we often had to stand next to the projector and translate the dialogues live. It’s almost like translating the subtitles impromptu, while lowering the film audio. This was, however, not required while screening for students in urban areas,” Basu recalls. After several such screenings in different parts of the state in 2013, the People’s Film Festival started as a three-day, open-to-all event of independent cinema—short and long documentaries and fiction—in 2014.

The PFC does not accept donations or sponsorship from any government institution, corporate house, or NGO. None of its events requires a ticket or a pass. The organisation and its activities have been sustained by the monthly membership fee and donations. It decided to stick to this model even for the film festival, which required around Rs 4 lakh. “Those who donate also tend to turn up at the screening events, often bringing more friends along,” she says.

The group has always paid extensive attention to campaigns ahead of the events, from posters and promotion campaigns using cars along with a microphone to skits by the street side. The group is able to meet its fund requirements during the festival, where a decorated donation box is kept at the venue. The audience has contributed amounts ranging from Rs 100 to Rs 10,000.

Over the past few years, the number of members of the collective has stayed around 30. Of them, about 10 have been with the PFC since its early days. During the annual film festival, the group gets about another dozen volunteers, mostly college and university students. This event that is less than a decade old has become a part of the city’s cultural calendar. PFC has been receiving 1,500-2,000 submissions of short films and documentaries for the festival for the past four-five years.

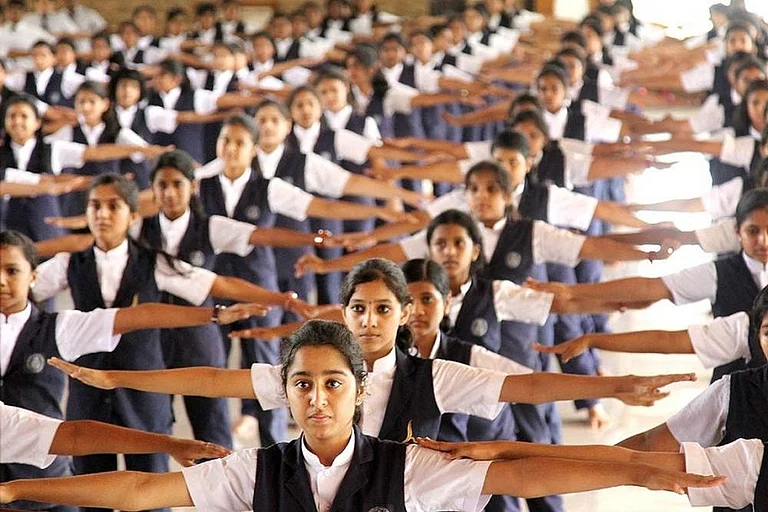

In 2016, the group launched a new initiative called Little Cinema, screening films for children. This initiative was taken to government schools and localities where the underprivileged live—from the slums of Calcutta to the far-flung districts of Murshidabad and Uttar Dinajpur. These programmes were held in association with local, rights or cultural organisations. One of the happy outcomes of PFC’s initiatives has been that a few college students in Calcutta have showing up regularly at festival venues. These students had developed a taste for cinema in their school days in Raiganj, a town 400 km north of Calcutta, after PFC members brought their film festivals here for three successive years. These young adults had enjoyed attending these festivals and those memories have propelled them to continue this activity for the years to come.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Cinema of and For the Masses")

Liked the story? Do you or your friends have a similar story to share about 'ordinary' Indians making a difference to the community? Write to us. If your story is as compelling, we'll feature it online. Click here to submit.