Phulwa gire-la chapal pa gamak aawela

Papa aisan bar khojani tensan rahela

Jaake Dilli-Ludhiyana mein basal rahela

[The flower fell down on the sandal and is spreading aroma/ O papa, you found me such a groom who gives me tension/He often goes and lives in Delhi-Ludhiana]

—Bhojpuri song translated by Asha Singh in her paper ‘Folksongs as an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women’s Articulations of Migration’

“Dear husband, I bought a tika (forehead ornament) in a jiffy

But in the rush, a portion of it fell down

My dear love, I will shower all my youth on your lovely face,

In which month will you come?”

I will not come in Jeth, Baisakhi (May, June)

I will come in the month of Sawan (August)”

–‘Gaali Geet’, a song sung by ‘left behind’ women in Bihar

Married when she was just 15 years old, Pata Mondal spends her days tending to her in-laws’ Der kathajomi (about 170 gaj, or 1,600 sq ft of land) in the Sunderbans in West Bengal while also looking after her two-year-old son. Her husband, a migrant worker, lives in Assam where he works as an attendant. He gets leave four times a year; it is only on occasions like Durga Puja and Diwali that he comes home but Mondal feels that it is barely enough time for him to get to know his son. When asked about herself, Mondal, whose married life has been one of loneliness and ennui interspersed with anxiety, says, with a sigh, “In eight years of marriage, I have barely lived with my husband for a year in total.”

The land that she tills is not her own. The house she lives in is in her husband’s name. Mondal has no income, and stepping out for an evening walk is the only time she gets to herself. It’s a lot of loneliness but no solitude, she says. When the COVID-19 lockdown hit, the 23-year-old had been pregnant with her son. She recalls the days of anxiety and horror spent locked in her thatched shanty, hoping for a miracle. “I thought I would lose the child. So many people were dying.” Her husband was working at a construction site in the Andamans at the time and Mondal recalls how he was stuck there for five months. “I had to take loans to secure money for his passage back. We have not been able to pay them back yet,” she says.

Then there were the cyclones — Amphan in May 2020 and Yaas a year later. Both times, Mondal’s husband was far away from home. The cyclones left acres of farmland inundated with saline water in the Sunderbans region, and the roof of the Mondals’ house caved in on one of the two rooms that the family of seven occupied. The damage has put further financial strain on the couple. “There isn’t enough arable land left for us to cultivate. We grow what we need but now we mostly rely on state-supplied rations and relief materials for survival,” Mondal says. She adds that her husband sends home about Rs 6,000 a month which is barely enough to feed seven mouths and pay off debts. While he is away, Mondal is the one who has to deal with lenders who, every now and then, come asking for their money back.

“Sometimes I wish that he would take me along with him. Survival can be hard here, especially for women like us,” she says. But she knows that it’s not possible. Her husband does not earn enough to accommodate her and the child in Assam. Moreover, she has to stay at home and take care of the child and her elderly mother-in-law. “That’s my duty as the wife,” she laughs.

Mondal’s story echoes that of millions of women in India whose lives are directly impacted due to economic migration. Yet her story is relegated to the footnotes of the migration saga that shapes India. In terms of economic contribution, Mondal’s labour in the fields and the kitchen doesn’t seem to count. She is but a ‘dependent,’ with the added financial liability of an infant.

Miles away, in a village in the Muzzafarpur district of Bihar, 48-year-old Medina Begum has more autonomy than Mondal. She supports her family by working as a construction worker under MNREGA—a scheme that is supposed to guarantee at least 100 days of paid work in a year and pays between Rs 210-Rs 228 per day of work. But in the last year, Begum says, she barely got 20 or 25 days of work. To add to her woes, her husband and son have been living at home ever since they lost their jobs during the pandemic.

Whether she earns or not, the kitchen is Begum’s territory and amid skyrocketing food prices, she often finds it difficult to make ends meet. “I don’t know how to feed them on such meagre income,” she states.

In Katargaam—an industrial region in Surat, Gujarat—Bharti, a migrant worker from Uttar Pradesh, says that she moved to Gujarat with her husband six years ago and has since been working as a saree weaver. She lost her job last year when over a dozen textile mills shut down post-pandemic. The family now survives on her husband’s daily wages. Bharti who has two children often feels a sense of being ‘othered’ in a city that treats her and her family as ‘outsiders.’ She misses home and the open fields of her village. But she knows that back in her village in Baliya, there isn’t any work and therefore, no future for her children.

Of Women Left Behind

In her work on migration and marginalised women, artist Ranjeeta Kumari from Patna documents the invisible stories of women’s labour and loneliness through visual poetry. Her work explores the gap between domesticity and the dreams of the women who are ‘left behind,’ by repurposing the objects they use in daily life into reflections of their fantasies. In Behind the Lines, her watercolour series, the humble mitti ka chulha (earthen stove), kadhai (metal pan) and channi (sieve)—articles of duty and domesticity—are fused with intimate parts of the woman’s body such as her hair or sequins from her saree.

“What do they imagine while cooking and cleaning, these ‘left behind’ women? What do they dream about in their solitude?” Kumari asks. In many of the images, her subject’s dreams and reality fuse into kitchen smoke. “The artworks were meant to highlight the links between domesticity, aspiration, and the unacknowledged labour of women who are left behind or spend their lives within the char deevar (four walls) of their homes,” says the artist.

To add to the financial instability, the COVID-19 pandemic may have also contributed to anxiety in the minds of migrant workers at the prospect of leaving their homes behind.

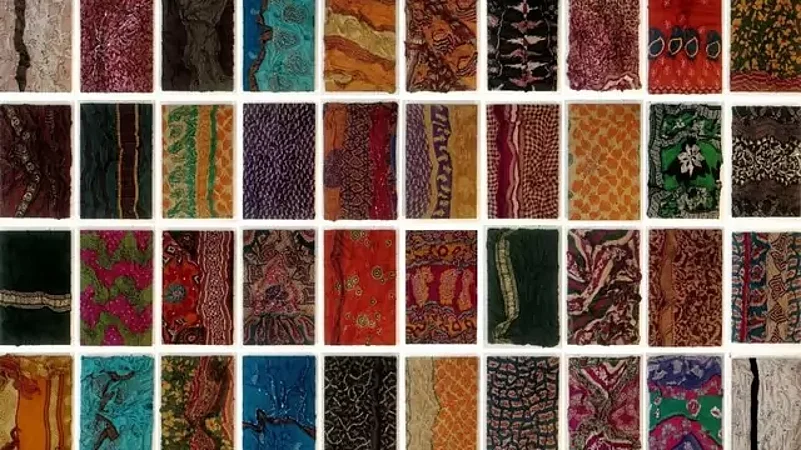

Kumari’s series titled Portraits of Women was created by repurposing old sarees worn by the women she has known. Though there are no faces in the portraits, the sarees are indicative of an individual identity that remains invisible, much like the women who own them. While they speak to the viewer at an emotional level and are derived from her personal experiences, Kumari’s visual poetry is also a pointed reflection of the consequences that migration and income inequality have on women like Mondal and millions of others. Is there anything they can call their own other than the chulha and the saree, the artist seems to ask.

Under-paid and Under-acknowledged

The 2001 Census showed that about 154 million out of a total of 221 million female migrants (69.6 per cent) reported marriage as the reason for migrating. But a more nuanced reading of the data showed that in rural areas, 31 per cent of the female migrants who moved because of reasons pertaining to marriage were working, as per the data of the National Sample Survey of 2007-08. Thus, women who moved because of marriage constitute a large share of the female workforce.

Studies of migration in India tend to focus on economic aspects like employment and income while neglecting the impact that migration has on the physical, mental and financial health of the women involved. “Migration is always a household matter as it impacts the household economy and interpersonal man-woman dynamics and familial relations. But women, as stakeholders, remain invisible as they do not directly participate in the employment or income generation sector,” says Kanhu C Pradhan, a researcher at the Centre for Policy Research. Unpaid labour is one of the biggest obstacles in the path of women’s economic emancipation. According to an Oxfam report, women perform 75 per cent of unpaid care around the world. In India, the unpaid work of women including domestic chores and farm labour would account for 49 per cent of the gross domestic product if accounted for in monetary terms.

Pradhan is of the opinion that many states in India continue to fare badly when it comes to improving the living and working conditions of female migrants, which could result in women dropping out of the migrant workforce.

In 2019, the BJP government at the centre launched the ‘One Nation One Ration Card’ scheme which allowed for the portability of PDS benefits. In theory, a migrant worker with documents from Bihar can get access to subsidised rations and other benefits offered by the destination state. However, Pradhan points out that theoretical entitlement often fails to translate into on-ground assistance especially because officers in the host state demand proof of residents which cannot be furnished by urban migrants who often live in informal rented accommodations without proper proof of residence.

To add to the financial instability, the COVID-19 pandemic may have also contributed to anxiety in the minds of migrant workers at the prospect of leaving their homes behind. “Many are hesitant to move their families to cities as they fear a repeat of the horrible experience migrants had in 2020 when the government imposed a sudden lockdown,” points out Pradhan. While it is difficult to assess the total impact of the migrant crisis on women, stories like those of Mondal, Begum and Bharti point to the need for more nuanced research that looks at women not just in terms of numbers but also in terms of their lived experiences which otherwise would be lost to the margins of history.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Colliding Invisibilities")