On Monday, a street vendor in Delhi’s Kamla Nagar market was charged with obstruction of a public way. This was one of the first cases registered under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, which has now replaced the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Similarly, in Bhopal, a case was registered against a person for obscenity in a public place. These cases highlight the extent of transformation, or lack thereof, that the new criminal laws have brought to India’s criminal justice system (‘CJS’).

Both cases have imprints from the system’s colonial past. The former symbolises the state’s excessiveness against its most marginalised sections, while the latter shows the persistent utilisation of a provision rooted in Victorian morality—both colonial relics.

While these laws were introduced with the promise of decolonising the criminal justice system and shifting the focus from punishment to justice, the actual changes reflect minimal progress in this direction. In fact, the efforts lack any substantial engagement with the ideas of decolonisation and justice.

Why decolonising the criminal justice system is important

India’s CJS, in its current form, was conceptualised in a colonial setting. It was created and implemented by a colonial administration. While introduction of the Indian Penal Code,1860, Code of Criminal Procedure,1872 and the Indian Evidence Act,1872, did modernise the CJS considerably, certain problematic underpinnings persisted.

The CJS was designed as a paternalistic system aimed at civilising Indians and used for the economic and political exploitation of the Indian subcontinent. Laws, legal procedures, and institutions were all employed to achieve this for the colonial administration. This led to extraordinary control mechanisms and the imposition of Victorian moral standards on Indian society.

Preventive detention laws, wide powers of arrest for the police, surveillance, vague and omnibus provisions criminalising any expression of dissent were hallmarks of the colonial CJS.

The enduring colonial legacy

Despite the promises of decolonisation, these same colonial practices and tools remain deeply embedded in the current CJS. Consider this -

There are around 25 preventive detention laws currently in force in India, many of them prescribing detention for everyday crimes, including 'anti-social behaviour'. From 2020- 2022, on an average 80,000 people were preventively detained under these laws every year.

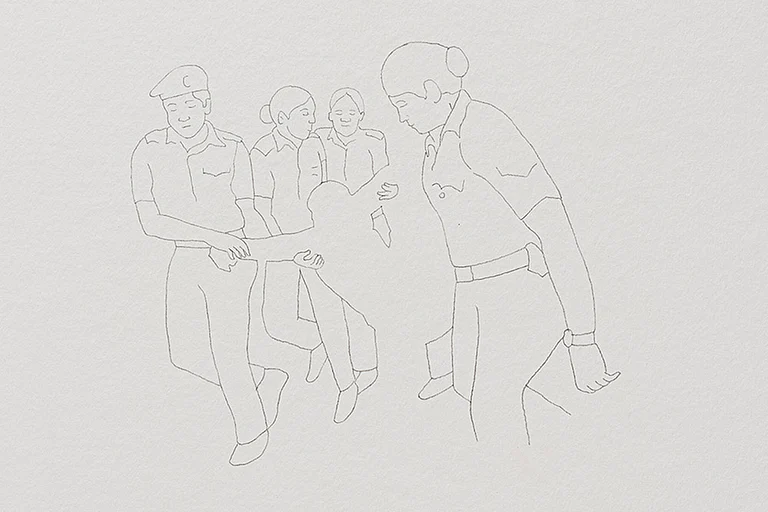

Chapters IX and XII of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (‘BNSS’) allow for extraordinary police powers of arrest, just like the provisions of the colonial CrPC - which in 2022 led to preventive arrests of over 8 million people.

Facial recognition technology is being increasingly used in policing across India, resulting in arrests, detentions, and random scanning of citizens nationwide. This widespread surveillance has found no recognition in these laws.

Similarly, wide and ambiguous provisions that criminalise free speech and expression, such as the offence of publishing 'misleading' information and offences against national integrity, continue to persist in the BNS.

The colonial penal policy

To further illustrate the enduring colonial legacies, consider the cases highlighted above. For the offence of obscenity [Section 296, BNS]—an offence vaguely defined to criminalise any act that is deemed obscene and is to any person's annoyance—a person can be sent to jail for up to 3 months or fined Rs. 1000. This is the exact same punishment that the law imposes for assaulting or using criminal force [Section 131, BNS]. It is also three times the punishment for wrongfully restraining a person under Section 126 of the BNS.

There are numerous such instances where similar punishments have been prescribed for vastly different offences and vice versa. For instance, making false statements on oath or affirmation [Section 216, BNS] is punishable with imprisonment up to 3 years and so is subjecting a woman to cruelty [Section 85, BNS]. Similarly, while fraudulent cancellation of a will, authority to adopt or valuable security can attract imprisonment up to 7 years or life imprisonment, the buying, hiring or obtaining a child for prostitution attracts maximum 14 years, but no life imprisonment.

This arbitrariness and inconsistency in punishments under the BNS, are also a relic of the colonial past, where criminal laws and jail terms were deemed appropriate responses for any form of deviance and very little thought went into understanding the value of such punishments. Otherwise, why would annoying someone attract the same punishment as assaulting someone?

Some notable changes

The new laws do introduce some notable changes to the CJS. It recognises community service as a form of punishment and introduces gender neutrality to offences such as ‘Voyeurism’ and ‘Assault to disrobe a woman’ with respect to the offender. Further, victims are assured timely updates on the progress of investigations. Forensic investigations are mandated for offences punishable by seven years or more imprisonment and specific timelines have been set for certain processes.

However, when the edifice of the colonial CJS remains intact with all its tools and policies, mere cosmetic changes and integration of technological advancements into the system, do little in the way of decolonisation and creating a citizen-centric CJS.

To truly decolonise India's criminal justice system, it is crucial to address its colonial foundations through legislative changes and a fundamental reimagining of institutions and objectives. As long as preventive detention, extraordinary police powers and pervasive surveillance persist, a just and modern CJS will remain unattainable.

(Naveed Mehmood Ahmad is Team Lead, Crime & Punishment at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy)