On September 12, after the Congress announced the route for Rahul Gandhi’s ‘Bharat Jodo Yatra’, the CPI(M)’s official twitter handle posted a caricature of the Gandhi family scion, asking if the rally should be called ‘Seat Jodo’ instead. It said that keeping the rally duration in Left-run Kerala at 18 days against only two days in the BJP-ruled Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, was a “strange way to fight BJP–RSS”.

The Left, surely, was expecting the Congress to invest more time and effort in the BJP-ruled states than the one ruled by a ‘friendly force’ like them. Measured in its response, the Congress was quick to announce that the rally duration in Uttar Pradesh was five days, not two. Senior leader Jairam Ramesh said that the CPI(M) should have kept in mind the various factors, including security, which led to the finalisation of the route.

Rahul Gandhi’s yatra connects India’s length from Kashmir in the North to Kanyakumari in the South but not the breadth—it leaves out Gujarat in the West, West Bengal and Bihar in the East and the whole of the Northeast.

ALSO READ: Bharat Jodo Yatra: Poised To Make A Mark

Once arch-rivals in the national space in the years after Independence, the Left and the Congress have come closer since the 1990s with the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at the Centre—citing protection of the secular fabric of the country from Hindu nationalists.

However, the small southern state has been a thorn in their friendship. Kerala is not only the last bastion of the Left, where they are in power, but also a Congress stronghold. The differences intensified after Rahul Gandhi decided to also contest from Kerala’s Wayanad parliamentary constituency, besides his home turf of Amethi in Uttar Pradesh, in 2019. Wayanad proved a saving grace as he lost from Amethi. Whether it was an effect of his candidature from the state remains debated, but the Congress won 15 of the state’s 20 Lok Sabha seats, nearly 30 per cent of the 52 seats it won nationally. Two years later, the Left returned to power in the state, marking the first instance in four decades of the ruling party retaining power for more than one term.

No wonder then that the Congress and the Left are trying their best to get as many parliamentary seats from this state as possible in 2024. In September, after the CPI(M) criticised his ambitious march on foot, the Kerala Congress leaders dubbed the CPI(M) as a ‘team of BJP–RSS’. Rahul Gandhi has, though, so far kept his focus on criticising the BJP and its ideological parent, the RSS, on both social and economic issues, during his yatra in Kerala.

ALSO READ: Bharat Jodo Yatra: History In The Making

A Friendship of Compulsion

If the BJP has managed to bring the Left and the Congress closer at the national level, Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress (TMC), too, has played a certain role in this. West Bengal, with 42 Lok Sabha seats, has stood witness to a largely contrasting scene compared to Kerala, exhibiting the best example of the Congress–Left bonhomie.

Cornered initially by the TMC and later by the big-bang entry of the BJP after 2014, they forged an electoral understanding in the 2016 Bengal assembly elections, failed to reach a seat-sharing agreement at the eleventh hour in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and again came together to fight the 2021 assembly elections in alliance.

Here, if the Congress has to fare any better than its miserable performance in 2021 in West Bengal, it has to recover ground it lost to the TMC. An offshoot of the Congress, the TMC eventually grew bigger and effectively marginalised the parent with a sustained poaching drive on leaders, including MLAs and MPs.

The TMC has extended its mission to establish itself as ‘the real Congress’ to the northeastern states of Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya and the western state of Goa, building its organisation mostly by poaching Congress ranks. In Meghalaya, the Congress’ Mukul Sangma joined the TMC along with 11 more MLAs, turning the TMC into the main opposition party in the state Assembly overnight. Even though the TMC’s Goa mission failed in the assembly elections last year and its performance in the Tripura rural poll was far from impressive, the Congress bore its brunt.

In Assam, the largest northeastern state with 14 Lok Sabha seats, though the TMC’s focus is mostly on the Bengali-dominated areas of lower Assam, its foray is likely to hurt the Congress more than the BJP, according to political observers. Ripun Bora and Sushmita Dev, two former Congress leaders currently leading the TMC’s charge in the state, have repeatedly claimed that Banerjee can provide better leadership against the BJP than any Congress leader. Dev, now a Rajya Sabha MP, is also looking after the TMC’s organisational affairs in Tripura.

Dwaipayan Bhattacharya, a professor of political science at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, thinks that the fight for secularism alone cannot help the Congress in its contest with other non-BJP parties. This is especially because policy differences between the Congress and other secular forces like the Left and the TMC are not very clearly distinguishable. “The Congress needs some kind of federalism in the organisation. It has long remained heavily centralised and high-command dependent, which is why they often failed to address the questions of regional aspirations. They need to build state-wise socio-cultural movements from the grassroots level if they have to recover,” says Bhattacharya.

The desperate situation in Tripura has possibly prompted both the Left and the Congress to extend their camaraderie to the northeastern state, where they remained bitter rivals for several decades until the BJP swept the 2018 assembly elections. Here, the alleged unleashing of political violence by the BJP on Opposition parties is bringing the Left and the Congress closer, with Manik Sarkar of the CPI(M) and Sudip Roy Barman of the Congress publicly speaking on the need for ‘all secular democratic forces’ to come together against the BJP for the 2023 assembly elections. However, the refrain sounds more like a message to each other.

Apart from the TMC, the Congress has to contend with a new challenge in the form of TIPRA Motha. Launched by former state Congress president and Tripura royal family scion Pradyot Deb Barma, the outfit has gained significant influence in the 20-tribal dominated assembly seats. Debbarma is unlikely to respond to an alliance offer, political observers feel.

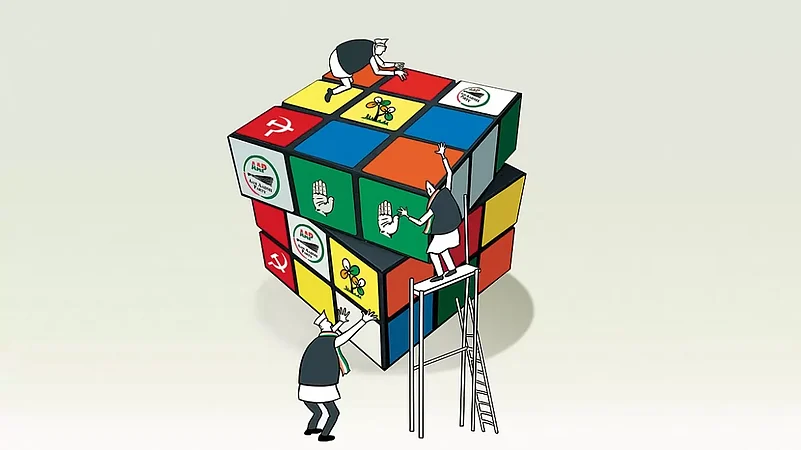

Of course, there are other anti-BJP ‘secular’ forces with which the Congress is likely to enter into an electoral alliance, for instance, the Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar, the Nationalist Congress Party in Maharashtra and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam in Tamil Nadu. However, such alliances also bring the party in competition with other anti-BJP forces, which makes Congress’ recovery battle more complex ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

Policy Matters

When the Congress transformed from a national platform in pre-Independence days to the largest political party in post-colonial India, the party had three forces with a national presence in opposition, the Left (communist parties), the Hindu nationalists (Hindu Mahasabha, Bharatiya Jana Sangha and Ram Rajya Parishad) and the socialists (under leaders like Jayprakash Narayan and Ram Manohar Lohia). While the Left and the socialists remained the dominant opposition forces till the mid-1960s, the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who also professed to socialist ideals, has been credited with having provided “a centrist leadership to a right-dominated” Congress, in the words of historian Suranjan Das. After Nehru, his daughter Indira, too, pushed for a socialist agenda between 1969 and 1976 and had even got the Left support both inside and outside the Parliament. After her, the Congress has mostly been seen as sitting ‘right of the centre.’

Meanwhile, its principal rival also changed. The socialists splintered into regional forces from the 1980s onwards, the growth of the Left stagnated and the Hindu right emerged as the main opposition force at the national level in the 1990s. Besides, there was the rise of regional forces, many of them offshoots of the Congress, differing little on ideology or policy and banking mostly on the personality cult of their founder leaders.

According to Rahul Verma, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research and co-author of Ideology and Identity: The Changing Party Systems of India, there is little distinction between the Left and the Congress when it comes to social policies, even though these parties have very different positions on economic policies. “Despite this, the main distinction between the Left and the Congress in Kerala lies in their social base. The Congress gets more votes from religious minorities, both Muslims and Christians, whereas the Left relies more on Hindu votes in Kerala,” Verma tells Outlook.

There is little distinguishable difference between the Congress and the TMC on both questions, though the latter is an offshoot of the former, he says. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which is “trying to pitch itself somewhere between the Congress and the BJP on both social and economic policies”, is more clearly distinguishable from the Congress. He sees the AAP as poised to be the Congress’ principal challenger in becoming the second largest party of the country, especially if AAP equals or surpasses the votes that the Congress garners in the Gujarat assembly elections.

Bhattacharya, while noting that the Congress is an all-India party with the potential to act as the fulcrum of an opposition alliance against the BJP, points out that the party’s “hugely depleted organisational strength in many states”, coupled with strategic mistakes on leadership questions, has repeatedly troubled the party. “Since most parties now follow certain forms of welfarism in their economic policies, the distinction is often blurred. However, building mobilisation from the grassroots to establish the welfare benefits as rights can give a party an edge over the others,” he says.

Verma, on the other hand, opines that since there is little difference between the social policies of the Left, the Congress and the TMC, the Congress will have to exhibit greater energy to perform better than these parties in Kerala, West Bengal or for that matter in some northeastern states in elections next year. “Strategy options for the Congress are now limited. Policy positions cannot change overnight and there is no guarantee of success even if they change. If the Congress knew what it needed to do, they must have already put a plan in action,” Verma says.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Marriage of Convenience")