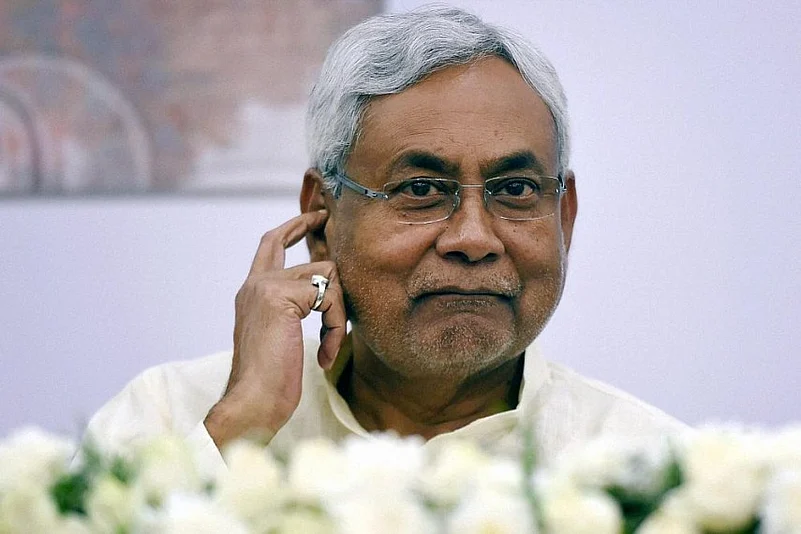

Though its timing may be politically intriguing, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s campaign to liberate the Ganga from the clutches of the controversial 42-year-old Farakka barrage, located about 16 kilometers from the border with Bangladesh in Bengal’s Murshidabad district, is in tune with the centre’s quest for making the country’s most sacred river to flow uninterrupted (aviral) under Namami Gange Yojana – the ambitious Integrated Ganga Conservation Project.

Ever since it was commissioned in 1975 to divert water from the Ganga to resuscitate then Calcutta port, the Farakka barrage has remained a political flashpoint between the two countries. Despite the existence of a Joint River Commission (JRC) to monitor lean-season flows down the barrage, there are no two opinions among any of the 156 million Bangladeshis that the barrage has done irreversible ecological harm to the lower riparian.

Such has been the popular sentiment in Bangladesh that every conceivable problem in the country is attributed to the impact of Farakka. Not without reason, as the JRC has estimated that loss to agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and navigation in Bangladesh on account of reduced flow in the river was as high as US$3 billion during 1976-1993. The losses have only continued to mount, fuelling inter-generational hatred among the masses towards their powerful neighbor.

By calling for dismantling Farakka, Nitish Kumar has spotlighted unmitigated collateral damage upstream of the barrage in Bengal as well as Bihar. Holding it responsible for the floods in Bihar, the Chief Minister has called for removal/decommissioning of the Farakka Barrage.

It is a bold undertaking by Nitish Kumar, bolstered by the fact that 2017 marks the centenary year of Gandhi’s Champaran Satyagraha when tens of thousands of landless serfs, indentured laborers and poor farmers were liberated from ruthless militia of their colonial masters. The present campaign is distinct as it seeks to liberate the river; a lifeline for millions, from the reductionist engineering that has only spread misery, both upstream and downstream.

While political motivation for his campaign remains unclear, Nitish Kumar has voluntarily lent political voice to decades of research which suggests that in addition to reducing river flow and consequent salinity ingress in the Sundarbans, the back waters have caused unwarranted floods and unmitigated riverbank erosion upstream of the barrage. The memory of 2016 floods that impacted over 22,000 people in 31 villages in Malda district is fresh in peoples’ memory.

Opening 109-odd gates of the 2.5 kilometer barrage may involve multiple actors. Not only is the functioning of the barrage governed by a bilateral treaty, the massive structure is located in Bengal and is under operative control of the Ministry of Water Resources. With billions of tons of sediments accumulated upstream of the barrage, any act of decommissioning will need detailed assessment of river’s complex eco-hydrology and fluvial geo-morphology.

While there is no denying that seeking uninterrupted river flow is a noble cause, and liberating the Ganga a long drawn out process at that, Nitish Kumar can serve the cause better by first letting rivers in north Bihar free of their embankments. If the Farakka barrage has been the cause for floods in Bihar, the eight major rivers,including Kosi, Baghmati and Gandak, are no less in their contribution to floods in the state!

All major rivers in Bihar have been jacketed between their banks. As a matter of fact, the politician-engineer-contractor nexus is so well entrenched that at any given time of the year either some length of the embankments is under repair or a new length under construction. No wonder, cumulative length of embankments on the rivers in the state is 3,620 kilometers. And, under undisputed political patronage the work is far from finished.

The engineering solution of raising the banks of the river, called embankments in engineering term, has raised the river bed higher than the adjoining lands. It is no secret that the Kosi river flows some 15-20 feet above the ground level at many sections of its embanked length. Thousands of hectares of adjoining land have been water-logged for good, as the raised embankments impede drainage into the river.

It is hard to believe that Nitish Kumar is unaware of these facts; he had been on the scene ever since he was a member of the Bihar’s Second Irrigation Commission in 1994. However, the story of the sorrow of Bihar doesn’t end here. There are 698 villages trapped between these embankments in Bihar. A conservative estimate indicates that no less than 40 lakh people live within these embanked rivers, their only escape being to face humiliation of migration to Mumbai and Delhi.

Having raised the issue of man-made disaster like the Farakka barrage, it is no less compelling for Nitish Kumar to address the plight of his riverine population first. By freeing rivers of north Bihar, he can erase the ignominy of people of Bihar.

Farakka can still wait, Mr. Kumar!

(Author and analyst, Dr Sudhirendar Sharma was the member of the Independent Fact Finding Team that had published Kosi Deluge: The Worst Is Still To Come a month prior to the devastating Kosi Floods in 2008)