A small tiffin box that has some leftover daal from the morning meal, a couple of clothes wrapped together in gamchas, and a box of earthen toys for her children to play with—that’s everything Anita has in here, at the Mori Gate relief camp in Delhi, where hundreds of people affected by floods have sought shelter. As the water levels recede near their home, hope recedes too. “I went home today to see what is left of it. Nothing. The little that was not drowned has now been stolen. My door’s lock was broken and all my belongings are nowhere to be found,” cries Anita, a young mother to four children.

While children play around in the basketball court of Sarvodaya Vidyalaya, where the camp has been erected near the Yamuna Ghat, mothers look distressed. Most of them work as florists at Yamuna Bazaar market and earn about Rs 200-300 a day. Their husbands work as migrant workers in other states or work at the nearby Nigambodh Ghat. With a meagre monthly income, families here now worry about how to rebuild the homes that have been all destroyed by the flood as Yamuna water levels broke a 45-year-old record and crossed the danger mark.

Around 250-300 people from Yamuna Bazaar, Anguri Baag, Nili Chetri, and areas adjoining Nigambodh Ghat have taken shelter at Mori Gate. After they visit their homes every morning, to take note of the damage and undertake the cleaning process, they return in low spirits. “There is nothing that is left of us. We have never seen floods of this extent. All our furniture has been damaged, rooves have fallen apart, and there is so much mud and silt covering everything,” says Sibha Devi, 48, a resident of Yamuna Bazaar.

Similar worries are echoed by several others who do not know when they will have a home again, and how they will rebuild them. “With all our savings gone and bare minimum earning, I do not know where will I go with my children. My husband does not stay here and works in Jaipur. He does not earn much either to be able to build a house so soon,” cries Sharda, a 25-year-old woman with three children.

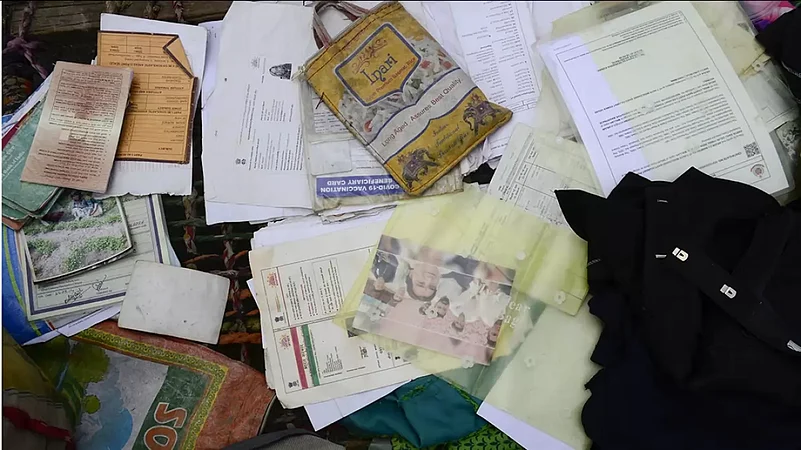

With everything that has been washed away by the floods, children wear a face of gloom because it’s their education that also comes under question. A 20-year-old Munni, who had to leave her education two years back due to an economic crisis arising from the Covid lockdown, was preparing to join an open school to pursue a course in stitching skills. However, whatever books and documents she had gathered over time, are all lost now. The losses that every family here incurred during the pandemic were slowly dying out when suddenly the floods added to their woes.

On July 11, the Delhi government said it has shifted over 7,000 people to nearly 2,700 tents and rescue shelters after the water level in the Yamuna River went beyond 206 metres. The Yamuna had breached the ‘danger mark’ of 205.33 metres on July 10 afternoon. By 11 pm. on July 11, it had swollen to 206.83 metres, which is its highest recorded level in 10 years, a senior official said.

Yamuna Bazaar is all Mud and Silt

A week after the floods hit the low-lying areas along the Yamuna Ghat, one would hardly find a concrete footing when they walk the streets of the Yamuna Bazaar. The boundary walls and walls of houses show a six-foot mark of mud lining. “This is the level till which the waters had risen,” says Khushi Chand, a social worker and a land rights activist.

While shopkeepers have just been able to open the shutters of their makaans and wipe the mud-wrapped goods to be sold, the youth is busy chasing snakes out of their homes and trying ways to drain the water.

“The government should be sending their volunteers to help in these relief works. However, no visits post the floods have been done yet. The workers are only found on the main road. The inner lanes and alleys are all left to be taken care of by the locals,” says Chand. He further accuses the government of a “wrong flood prediction”.

“On the night of July 11 (last Tuesday), the NDRF personnel came and chased locals out of their homes with sticks. People panicked and rushed out of their houses. Only two buses were provided for an area that houses nearly 500 families,” says Chand, adding, “Why could the government workers not turn up well before time and make the process a little less hassle-free? In that case, families would have had the time to at least grab their essentials and documents. More so, their entire flood prediction was wrong.”

Unequal Rehabilitation?

All their hopes have now turned towards the rehabilitation services of the government. At the Mori Gate camp, officials collected the Aadhaar cards and bank details of the people and promised each family a sum of Rs 10,000 for rehabilitation. However, people affected by the floods wonder whether this token amount would be of any help.

“It has taken us lakhs of rupees to build one small house and they are offering only Rs 10,000? Moreover, there is no electricity, and all meters have been damaged along with the pipelines. There is no clean water to drink. We want the government to first fix these basic necessities so that we can at least move back to our homes,” says 32-year-old Munni Devi.

No Documents, No Relief

The banks of Delhi’s Yamuna Ghat have seen a large influx of migrant workers whose documents are not from Delhi. And for them, there seems to be no relief.

Poonam, 30, who has been staying in Delhi for nearly five years for treatment at AIIMS, is running pillars to post to seek rehabilitation. Although Poonam’s parents were residents of Delhi, she was married in Uttar Pradesh’s Ghazipur district and all her documents belong to UP. She paid a rent of Rs 3,000 and stayed in Yamuna Bazaar. While her husband undertakes cleaning services at the Nigambodh Ghat, she can make no living on her own due to a brain illness. There is no hope for her family to survive this disaster, says Poonam.

“The government will not give me any money or provide help because my documents are not from Delhi. I feel so helpless, I have tried to explain to them the entire situation but they have shooed me away. What do I do? Where do I go? Is there no way that migrant workers from other states, who have been severely affected by the floods, will receive any help?” she asks.

No Relief, Yet Again

While there is a scope for rehabilitation, it is not equal for all.

Beneath the Sarai Kale Khan flyover resides nearly 200 families, who had to be accommodated in 15 camps which were put up but with no regular flow of electricity, water, and basic amenities. Mostly scrap workers, families here say that they will need weeks to clean the mud and repair the damages caused by the flood. Adding to that is the lack of official relief funds from the government.

“These are extremely backward areas. Why will the government care? All they did was put up camps, click a few pictures, had their show on media, and that’s that. No words of rehabilitation have been communicated with us,” says 50-year-old Sahir Ali, who now feels too nauseated within his own home because of the constant foul smell from the mud and the moist.

Ali, who buys disposed of aluminium cans and sells them to recycling companies, has suffered a loss of nearly Rs 75,000. Besides, families are also scared of the constant threats of snakes and insect crawling in and out of their homes.

Eviction: A Double Jeopardy

On either side of the flyover in Bela Estate, people, who have not got any camp to seek shelter, have put up tarpaulins to reside with their families. Till last week, they were staying along the Yamuna Ghat after their homes were demolished in March, early this year, due to a beautification drive ahead of the G20 summit.

“It was the government that destroyed our homes first and now it’s their action whose consequences have destroyed our homes once again,” says Heera Lal, who is staying inside one of the camps at Bella Estate.

Lal says that it took a media report for the government to allot them a few tents beside the tarpaulin structures, which have been put up by families themselves. But locals here cry similar allegations of all these being a show for the media. “The water tanker came only for one day. On another day, a local leader came just to distribute two bananas to each family and take enough pictures of their activities. All our food and essential supplies are coming from NGOs,” says Shanti Devi, who is staying with her three children under one tarpaulin.

Cause and Effect

Families staying here have been victims of a recent eviction drive following the construction of a biodiversity park. “A park that was estimated to be constructed at some crores of money has nothing left, not even anything worth one digit-sum maybe,” says Heera Lal, who believes it’s the government that is solely responsible for “messing up with the biodiversity of the area around Yamuna bank”.

“Floods of this extent never happened and this was bound to happen, nevertheless. When the new Parliament was being constructed, we would often see trucks of bricks and construction waste being dumped into the Yamuna. They would also take away sand from the Yamuna, which was long banned by the court in 2015. Yet they did. They destroyed the natural biodiversity in a bid to create an artificial one. And of course, this had to happen,” says Lal.

Commenting along similar lines, Shanti Devi adds that where they lived once, there was a sight of several peacocks. Ever since the construction work of the park began, several peacocks were spotted dead.

Despite possessing valid documents as residential proofs, families here have been accused of ‘illegally’ staying on the lands of the state. “Where else do we go? You throw us out telling us we are illegal migrant workers and then your man-made floods come as double jeopardy,” they say.

Domino Effect of Climate Change

Large areas along the Yamuna banks have seen migrations in two forms—settlements in jhuggis-jhopris and a post-independence urbanisation that has led to ecological degradation. While residents under concrete roofs sit safely inside their houses, it’s the other section—for who migration for work has been a desperate coping mechanism—are the ones who remain affected. And a rising climate change poses a further threat to their “illegal” settlements.

“What the state needs to do is identify areas that can act as natural buffers against these impacts of migration. Delhi has over 500 listed water bodies and many of them are now covered with either garbage or construction material and debris. The same has happened along the riverbed area in the natural drainage system. The government has ignored the settlement of people around these areas and the larger social cause behind it. And that kind of leads to the situation we are in,” says Dr Manu Gupta, co-founder of Seeds India, an organisation working around people affected by climatic disasters.

Dr Gupta believes that there is a strong linkage between climate change and the kind of migration we have seen in recent times. In a domino effect, environmental degradation has created climate refugees for several decades and some of the most environmentally degraded areas in the country have pushed people out, creating a large influx of migrants and internal displacement.

“There are certain traditional practices that allow them to stay in these areas but once exceeded, they are forced to resort to some of these desperate measures like migration,” says Dr Gupta. However, he believes that the Delhi floods, in some way, were man-made. “A lack of anticipation and poor maintenance of the system led to this kind of chaos. I think these floods could be better managed with better cooperation between states, and irrigation departments which often regulate water flows. I think this could have been averted altogether.”