The evocation of Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi, the country’s only female prime minister, seems be neverending in the political discourse. Like Banquo's ghost in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, their legacies continue to haunt Indian politicians – both the ruling and the opposition camps. Some utilise them citing the ‘secular’ credentials and others invoke the ‘horrors of Emergency’.

Since he became the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi brought in the legacy of Nehru several times. During a parliamentary debate in February, 2024, PM Modi said that he was “lazy”. In another instance, he said that Nehru “was against reservation”. However, politically Nehru had been considered one of the major secular and inclusive leaders both in colonial and post-colonial India. During the inauguration of Somnath temple, Nehru asked then President Rajendra Prasad to not attend the programme. In his letter, he clearly mentioned the Indian state cannot identify with any particular religion.

If Nehru has been one of the most sought-after figures for the BJP to criticise, Indira Gandhi is not far away. Just after the election results where the BJP failed to retain its absolute majority in the Parliament, the government issued a notification and declared June 25, the day when Emergency was declared, as ‘Samvidhan Hatya Diwas’.

Incidentally, amid the political drama, Kangana Ranaut-directed Emergency, in which she essays the life and political preoccupations of Indira Gandhi, was about to hit the theatres on September 6. However, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) stalled its release.

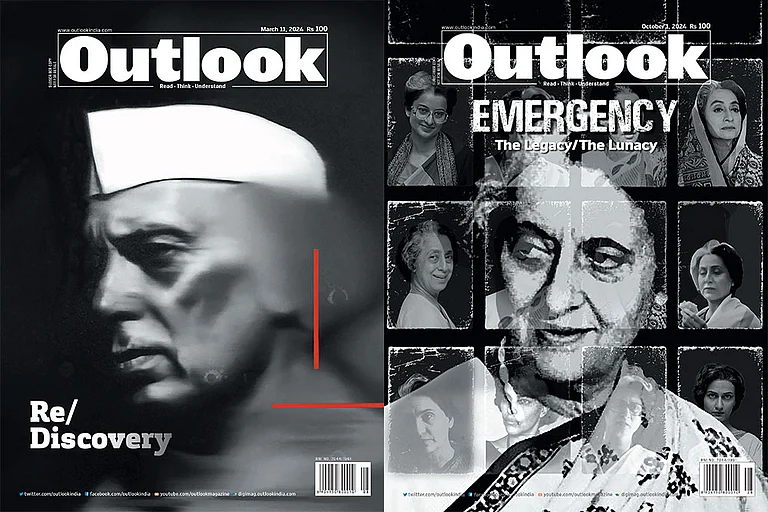

Read stories from Outlook's 11 March 2024 issue titled 'Re/Discovery'

The Emergency of 1975 is a pivotal moment in Indian political history. It was on June 25 that year, just a few minutes before the clock struck midnight, that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of internal Emergency that lasted for 22 months. It was one of the darkest periods for Indian democracy, characterised by press censorship, suppression of civil liberties and forced sterilisation.

Both Nehru and Gandhi have often been criticised for the choices they made during their tenures. But is that all their legacies entail?

In Outlook’s next issue, we not only take a look into Ranaut's film but also dive into what went on in those 22 months of Emergency. How did civil society react to the clampdown, and how did journalists and activists resist censorship?

In this issue, Kalpana Sharma writes about how Himmat Weekly, like a few other newspapers, ran blank editorials to mark the dark period. Kumar Ketkar writes about the exciting and challenging times for journalists who wrote in the volatile decade of the 1970s. Prem Shankar Jha writes on how during both the Emergency period and the last decade of the Modi government, his writing has been devoted to questioning the government’s policies and actions.

We also look into the BJP's and the Congress’ concerns about what they perceive as authoritarian tendencies. Indira Gandhi, like Nehru, remains a controversial figure and their decisions have impacted many. Perhaps, the Emergency will always overshadow the rest of Indira Gandhi’s legacy.