The story of the Ramayana has been retold many times and it is believed that there are more than 300 versions of the Ramayana. There have been myriad interpretations and retellings of these versions across the Indian subcontinent. The millennial generation has seen various screen adaptations of this epic, varying from Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan to Adipurush, the most recent and lavish Bollywood-ised version of the epic.

As of today, even after so many stage and screen adaptations, not many millennials can name more than three versions of the Ramayana. While some of us are busy debating upon the term ‘mythology’ or ‘itihasa’, some even refuse to accept that there are other versions of the Ramayana.

Many of us are even unaware that apart from the popular Valmiki and Tulsidas versions, there are different narratives written by women. We don’t come across enough titles that narrate the Ramayana from a woman’s perspective probably because we were so focused on deifying the central male characters that somewhere we may have neglected the female characters of the epic.

Much like history, mythology too can be a bit of a men’s club. Some popular versions from the 16th century have inadvertently incorporated the impact of socio-political influences of their times with regard to the status of the women in the story, viz. the ‘Lakshman Rekha’ incident, which although was not a part of the original manuscript, has now become a metaphor for women, thereby circumscribing their conduct. Some stage and screen adaptations have created strong impressions of the women characters in the epic, and we see a different portrayal of Devis vs. Rakshasis women.

Lesser-known women characters like Urmila (wife of Lakshman), Mandodari (wife of Ravana), Tara, Kaikesi, Kaikeyi, Shanta (elder sister of Rama), Manthara, Surpanakha, and Sarama (wife of Vibhishana) are neglected in the artistic interpretations of the epic. In our minds, we have a rather stereotypical sketch of their personalities, classified first by birth and further by deeds. Over time, we have come to believe them and we still stick to the monolithic side of the key characters.

Shanta, Urmila, Mandodari and Tara remained unsung and forgotten until the most recent retellings were published. Surpanakha and Kaikeyi are plainly seen as negative characters because they chose to stand up for themselves in the story. Ahalya, a woman defined with matchless beauty, the wife of sage Gautama, accused of adultery, was turned to stone after the curse of her husband when he found her with Indra; only Rama’s touch could release the curse. Sulochana, the virtuous wife of Meghanad and the daughter-in-law of Ravana, who immolates herself on the funeral pyre of her husband, remains lesser-known because she belonged to the anti-hero’s family. These women characters of the Ramayana struggle with existential, moral and reputational battles even in the most modern depictions.

In his narrative, Valmiki, who is known to be the first composer of the Ramayana, had presented rather illuminating perspectives about the status and the influence of the women. For instance, despite being called selfish, Kaikeyi’s wishes were upheld by Dasharatha and Rama, irrespective of the consequences. Valmiki also presented Surpanakha, a Rakshasi woman, as an impactful character in the epic. Even later narratives of the Ramayana had strong women influencing the course of events, providing useful counsel to the menfolk. They were a source of inspiration, defined as courageous, devoted and knowledgeable.

We celebrate Sita and her sisters for their immense contribution to Rama’s heroic journey, but on the other hand, the women of Lanka become victims of ‘cancel culture’ as they belong to the opposing side of the narrative, hence there are barely any retellings about the women of Lanka.

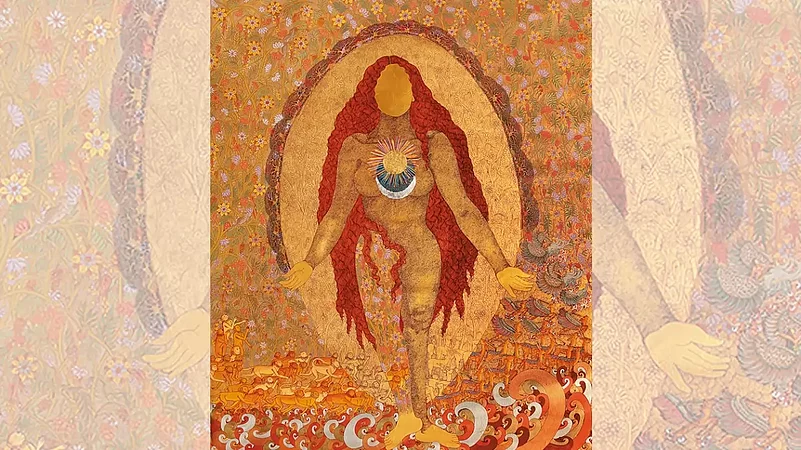

What is striking is that depiction of Devi and Rakshasi women today has been classified as per their roles into pre-defined narratives and we often come across misleading renderings of their appearance and behaviour. It is miserable to see how Surpanakha and other Rakshasi women of Lanka are not just depicted as ugly, but some television and stage adaptations have gone to the extent of giving them fangs and horns, as if we have not body-shamed them enough. Readers and viewers are thus conditioned to relate unattractive appearances with poor moral fibre. Trijata, the Rakshasi woman who befriends Sita and consoles her throughout Sita’s stay in Ashoka Vatika, is portrayed as pot-bellied and ugly even though she plays a positive supporting character. This shows how the appearance of a woman remains prejudiced based on her origin.

While ‘Devi’ women are portrayed as good, ‘Rakshasi’ women are depicted as ugly and evil. Disfigured women like Manthara with a ‘hunchback’ are portrayed as evil and manipulative, while beautiful women such as Sita and Mandodari are depicted as kind, pious and righteous. The physical traits automatically associate one’s outward appearance with character. Furthermore, depending upon the narrative and portrayal, a woman’s behaviour and character are perceived differently in the same story. Shanta and Surpanakha are both royal princesses; Shanta’s act of seductively dancing and luring a sage into marrying her is not despised because she is Rama’s sister, whereas Surpanakha’s behaviour when she liberally approached Rama for marriage is considered immoral because she is Ravana’s sister.

Similar to Medusa (from Greek mythology) and Lilith (from Jewish folklore), many women from Indian mythology remain misinterpreted and misjudged. In present times of gender equality and non-discrimination, if we review our perception, we may conclude that we have viewed many occurrences in the epic through the prism of patriarchy. Moreover, applying an intersectional lens to the portrayal of women in popular culture highlights how our perception can be highly misjudged and misleading.

The women of Ramayana seem to have been discriminated against, based on their birth (Devi or Rakshasi), gender, origin and political belief or background. Not only can it take away the essence of the ‘itihasa’, but upon a feminist view, this one-dimensional depiction of women has displayed inaccurate diversity even within womanhood.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Devi Versus Rakshasi')

Manini J Anandani is the author of Mandodari Queen of Lanka