Kenku, 50, hurries back to her hut after drawing about eight buckets of water. While she was drawing the precious liquid from the depths of the heated bowels of Rajasthan’s dry earth, six other women had kept her company, vigorously drawing their own share of water.

Kenku rushes back to apply ointment over the burnt skin of her neighbour’s son. The little boy, who constantly cries in pain, has sustained severe burns after a pot of boiling milk fell on his right leg.

His mother is probably kilometres away, working at a construction site. Medical facilities are scarce, which has worsened the wound. Water is scarce too, forcing Kenku to ration the quantity of water she can use to regularly clean the wound.

In Ramdev Nagar village in western Barmer, water is a precious commodity carefully utilised for drinking, cooking and feeding cattle, but seldom for cleaning and washing.

In the Sheo constituency’s Thar desert pocket, Ramdev Nagar, located in Rohidaala gram panchayat, showcases the severe water crisis afflicting Rajasthan’s more densely populated pockets.

Desperate cries for water begin before the break of dawn and continue till noon. Groups of women in and around villages, to date, walk for hours to fetch water. The bedis (borewell) built by the government dry up in summer. The tanka constructed for holding rainwater are often caked with silt deposits, which make water unpalatable in the hot season, when the tank runs shallow.

The big tanks, built at a few kilometres’ distance, often run dry as authorities fail to replenish them. Reverse Osmosis machines with instructive government slogans on the importance of water, lie locked up in a state of disuse. Walking to the neighbouring village—dominated by upper-castes—for water, too poses another set of caste-oriented challenges.

“Since 1952, multiple elections have been fought, but our only demand remains safe, clean and regular drinking water,” says Heeralal, a local villager and principal of a government senior secondary school in the Gagariya block. There are toilets built in almost every hut, but one may spot men and women walking distances to defecate. “What use are any of these latrines without water?” asks Kenku.

Water is primary to any development and its scarcity hampers various human needs and rights. Reports indicate worsening safe drinking water availability due to climate change, disproportionately affecting women and children. Rajasthan, constituting 5.5 per cent of India’s population, has only 1.1 per cent of the country’s water resources. Government data from the summer of 2022 reveals that out of 285 blocks, 203 were overexploiting groundwater, highlighting the critical water situation in the state.

“For 72 years, elections in Rajasthan have been fought on three issues—water, electricity, and roads—yet, it has been only a few years since electricity reached a few villages here. Not much luck with water,” continues Heeralal. During every election, tall claims promising har ghar paani (water in every home) take centre stage with every successive government ‘committing’ to it.

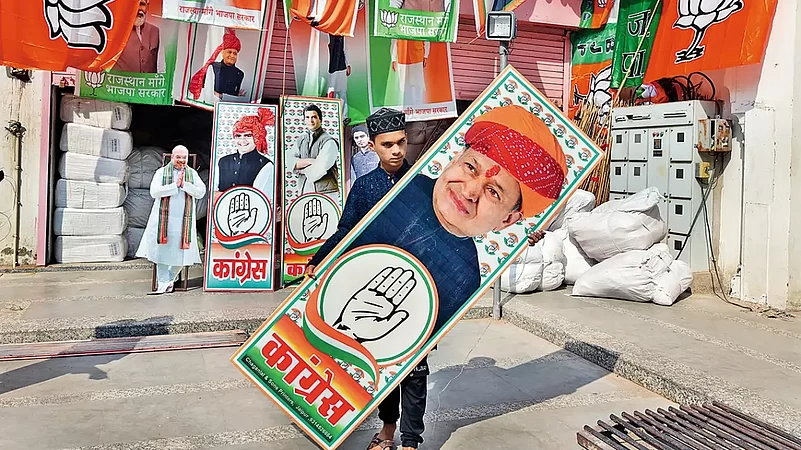

Since 1993, Rajasthan has witnessed alternating governments led by the BJP and the Congress. Both parties often point fingers at predecessors for the persistent water scarcity. This blame-game politics creates a destructive cycle, leaving the voters as the ultimate losers.

In Jaipur’s Vidhyadhar Nagar (rural), BJP MLA candidate Diya Kumari, a local royal, is cheered by supporters. Kumari is the granddaughter of Man Singh II, the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jaipur during the colonial era. In the same constituency’s Ward No. 2, Kaushaliya Devi Jangid pleads for regular drinking water. Kaushaliya Devi spends Rs 400 every third day to top up her 500-litre water tank. Kumari blames the Congress government and the Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) for the chronic water shortage. As a sitting BJP MP from Rajsamand, Diya Kumari criticises the Congress vis a vis development and advocates for a “double-engine” government to ensure Central schemes and water supply to every home.

Vidhyadhar Nagar has been represented by BJP’s incumbent legislator Narpat Singh Rajvi, who disappoints long-time BJP voter Kaushaliya Devi. Rajvi is the son in-law of three-time Rajasthan Chief Minister late Bhairon Singh Shekhawat. Despite Kaushaliya Devi’s Brahmin lineage and loyalty to the saffron party, she criticises Rajvi’s inability to provide water to the area.

There are other critics too. “The sitting MLA here has done no work. We don’t even expect it from him anymore. However, we trust Kumari, who is like our daughter. She will get this work done,” says Neha Gupta, another young woman from the Shankar Colony.

Internal party conflict arose when the BJP fielded Kumari, the sitting MP, instead of the incumbent Rajvi, who was denied a ticket from Vidhyadhar Nagar. Rajvi was shunted to another seat in the Chittorgarh region. Despite Rajvi’s 2019 promise to enhance water infrastructure, the region still faces water issues, with no improvements made during his tenure.

Water Woes

Interestingly, water, or rather the lack of it, has rarely featured as a key poll issue.

Kanaram Barupal, a young advocate from the Bandra region in Barmer, laughs when asked why the water crisis is not a broader electoral issue. With a disconsolate smile, Barupal says, “It’s shocking how people from outside Rajasthan believe that water is or should be an election issue. At the ground level, this is not even treated as an issue, let alone polls. People make peace with it.”

“People living in harsh conditions initially have hopes when politicians come to power because of their tall claims. When the time comes, nothing happens and as a result, the ability to hope for basic needs is shattered multiple times, over decades. They have come to terms with that and perhaps stopped demanding,” comments Chhavi Rajawat, a former woman sarpanch from Soda village in Tonk, who is known for her work in the area of water crisis management and rural development.

In Bindhani, Barupal’s ancestral village also in Barmer district, the water crisis persists. Pipes laid out near the Munabao Road, which leads to the India-Pakistan border hint at hopes tied to the Indira Gandhi and Narmada Canal projects. Although water has reached some areas like Ramsar, distant villages like Bindhani remain untouched, leaving locals longing for the promised relief from the Sardar Sarovar Dam water.

A lack of synergy between bureaucracy and politics has further worsened the water crisis.

“Either there is a lack of extensive research at the government level or the research is never being implemented. This could be due to a lack of collective enthusiasm to work towards taking sustainable measures for preserving water in a desert state,” says Rajawat, emphasising that if the government has limitations, the private sector must step in to mobilise resources. However, nothing is being done, and the state remains in a dark zone, an area where groundwater depletion exceeds the rate of recharging.

As an outcome of the water crisis, women’s lives which revolve around fetching water in the gendered spaces of the state are heavily impacted. “My entire youth passed by, collecting water. There were RO machines set here and there near our villages, but today they are all non-utilised and locked up due to lack of servicing over the years,” says Prameela, a 23-year-old mother from Ramsar.

At 18 years old, Prameela was married and moved to the outskirts of urban Bandra, where the water shortage is less severe. Despite challenges, she feels fortunate to have a chance to pursue higher education. While girls attend schools, inadequate infrastructure hampers their educational opportunities.

In a Gagariya block senior secondary school, students study on their own due to a lack of teachers in subjects like Urdu, English and Maths. Mid-day meals are scarce and despite complaints to district authorities and MLA Ameen Khan, there has been no corrective action. Despite these issues, Khan, a Congress incumbent, continued to win elections for five terms, making his removal difficult, according to locals.

“We have voted for the Congress and would continue to vote for them because, with the Congress, there is less danga (riots),” says Hakimram, a 75-year-old resident of Ramdev Nagar. Sheo, with a significant Muslim and SC/ST population, traditionally supports the Congress. Villagers face casteism and gender-based violence from neighbouring Rajput villages, whose upper-caste inhabitants are largely BJP loyalists. Residents like Radha, a 60-year-old Dalit woman, fear BJP’s Hindutva ideology might exacerbate their situation, making them apprehensive about the party gaining ground in the region.

At 84, Khan is one of the oldest candidates in the fray, having won the Sheo constituency five times since 1980. However, Khan’s candidature stirred another internal rift when speculations were rife about whether the ticket could also be given to the District Congress Committee president Fateh Khan. Ameen Khan accused Fateh Khan of dishonesty, offering his own son instead as his alternative. He claimed that the Congress would win Sheo only if either he or his son were given the ticket.

When Outlook visited the constituency, voters were divided over the choice of candidate, with a local voter even cautioning Congress won’t get votes, if Fateh Khan did not get a ticket.

“Vikas (development) is nothing. It’s about taking our money and giving it to us in twisted ways. We don’t care about this, but Fateh Khan must win,” the local resident said.

Winning with Welfare

In the 2018 Assembly elections, Congress got 99 seats, while the BJP won 73 out of the total 200 seats. Gehlot assumed power with support from the BSP and some other non-BJP legislators. Given the anti-incumbency trend, the battle in Rajasthan raises questions about a desire for change or continuity. “The locals hold high expectations from the government. When promises aren’t fulfilled, they seek change, aiming to replace them and nurture fresh hopes,” says Barupal.

Congress voters and MLA candidates are firm in insisting that there would be no anti-incumbency this time because people reportedly have their faith in the Congress on account of the “schemes” that its government has delivered.

In Jodhpur, Barmer, Udaipur Jaipur, and Alwar, locals’ opinions on Gehlot’s Congress government vary. Some continue to believe that Gehlot’s leadership and welfare schemes, like the Chiranjeevi Health Insurance, Annapurna food kits and free mobile phones, might ensure his comeback.

At the opposite end of the political spectrum, the BJP cadre and leaders feel that Gehlot’s schemes have been nothing less than an eye-wash. “The schemes have been refurbished versions of what the BJP had started at the state and centre levels,” says Balwant Singh, a Rajput voter from Gehlot’s Saradarpur constituency. He counters pro-Congress views, citing the cylinder subsidy as a modified BJP scheme. A section of the voters, confident of a Congress victory, however, cite the dominance of non-Rajput settlements in the area as the reason.

Speaking to Outlook, Diya Kumari criticises Congress for unfulfilled mobile phone distribution, claiming phones never reached many households.

“Giving out freebies is a way of insulting people. Locals in Rajasthan like to earn what they deserve. They need roads and water, not mobile phones,” says Kumari, who reiterates that the “essence of women empowerment” lies in eradicating the water crisis.

Despite praise for the Chiranjeevi health scheme, Barmer lacks proper hospitals, forcing villagers to travel 200 km to Jodhpur for treatment. Earlier this year, during a dengue-like fever outbreak, local residents faced dire conditions, with many having to seek treatment in Jodhpur due to limited space in the district hospital. These issues might transform into matters of electoral concern, though caste and community politics still dominate the spotlight in the state.

The Caste-Community Combo

Caste has always played a crucial role in Rajasthan’s politics. No party can secure substantial votes without support from dominant caste groups. Despite aspirations for progress, caste divisions persist, acknowledged by all, hindering efforts to transcend them. In the paper, titled ‘Politics and Caste in Rajasthan’, published by Indian Political Science Association, authors L S Rathore and K S Saxena write: “In the Indian political system, in general and Rajasthan politics in particular, caste has become a well organised, homogenous and articulate factor and State politics cannot be judged without a reference to caste. In India and particularly in the politics of Rajasthan the castes and sub-castes dominate social life and inevitably influence their members’ attitude to other groupings of a social and political character”.

In Vidhyadhar Nagar, the saffron party is likely to win due to its Rajput and Brahmin support among traditional BJP voters. Carved out in 2008, the constituency altered the caste dynamics, with various communities seeking representation. BJP fielded Kumari against Rajvi, while Congress struggled to find a suitable non-Rajput candidate. Sitaram Agarwal is now contesting on behalf of the Congress against Kumari in this evolving political landscape.

In Viratnagar, in the Kotputli-Behror district, locals seem to be backing Congress’s sitting MLA Inder Singh Gurjar to win. Traditionally, BJP supporters, the Gujjars (OBC), shifted allegiance to the Congress due to Sachin Pilot, who is contesting from Tonk. The community wields influence in 30 seats including Dausa, Karauli, Hindaun and Tonk. They support the Congress due to the perceived ‘vikas’, despite not specifically being aware of the accrued benefits. This highlights the shifting political landscape in the region.

These caste equations have sprung surprises for many parties over the years.

In Malviya Nagar, Congress MLA candidate Archana Sharma disputes claims of rising crimes against women, attributing increased reports to better reporting of such instances to the police. Rajasthan ranks second in reported rape cases as per National Crime Records Bureau data. Despite this, some voters believe Sharma could win due to her Brahmin identity. Brahmin and Vaishya voters hold sway in Malviya Nagar where the BJP has fielded incumbent MLA Kalicharan Saraf, a Vaishya. The election outcome remains uncertain amid these complex social and political dynamics.

Muslim voters in Rajasthan this time round, appear to be swaying towards the Congress; perhaps in a collective bid to resist the BJP’s Hindutva politics. In Alwar (urban), Mubarik Khan Malik, 24, tells how the BJP’s sadhu-sant (seers and saints) politics in the region only polarise one community. “They have not even won the election, and they have already started speaking about bulldozer politics,” says Malik referring to recent speeches by Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath and Mahant Balaknath, BJP’s contestant from the Tijara seat in Alwar, who has frequently made headlines for communal violence.

As she navigates the heat of the campaign for the upcoming state assembly polls, BJP’s Diya Kumari expresses hope that Rajasthan’s political and electoral discourse moves away from the twin phenomena of caste and community politics. But Rajasthan’s voters, for now at least, do not appear to be on the same page as their princess.

(This appeared in the print as 'Caste(e) Iron')

Shreya Basak in Jaipur, Barmer, Jodhpur, Dungarpur and Alwar