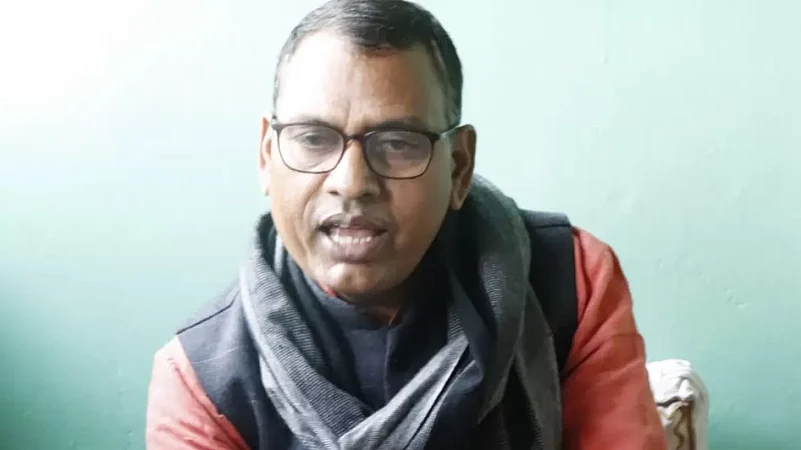

Translation of Dalit writing in different languages into English is essential for reaching a wider audience, claims Bhanwar Meghwanshi, a former member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and author of I Could Not Be A Hindu: The Story of a Dalit in the RSS.

“Hindi has its limitations and English has its advantages,” says Meghwanshi, whose memoir Mei Ek Karsevak Tha was first published in Hindi in 2019 by Navarun.

The Hindi original did not get much attention from either readers or critics.

“People read it, they said it’s a fine book,” says Meghwanshi. “But no major Hindi newspaper reviewed it. Some of the readers wrote about the book on social media, including their own experiences. But this, too, did not attract the attention of Hindi litterateurs.”

However, when the English translation by Nivedita Menon, professor of political thought at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi, was published by Navayana in early 2020, not only was it reviewed by the English media, Hindi newspapers and litterateurs also revisited it.

“At times, you get validation from an English translation,” says Meghwanshi.

Creative process and controversy fears

The book has a rather long gestation period — from social media posts to English translation and critical acclaim. “I wrote 52 chapters on Facebook about my days in the RSS,” says Meghwanshi. “My friends insisted that I give it the shape of a book.”

However, getting the book published was not an easy task. “Between 2014 and 2019, I sent the book to many publishers who asked for it. But neither did they reject it, nor did they publish it,” says Meghwanshi. “No one was ready to publish it.” Finally, in 2019, Navarun decided to publish it. “However, they were worried that it might lead to a controversy,” says Meghwanshi. “I told them if anything happened, we would fight it together.”

Despite the lukewarm reception that the Hindi original received, Meghwanshi was keen on an English translation. S Anand, the founder of New Delhi-based independent publisher Navayana, which specialises in bringing out Dalit writing, connected him to Menon. “I was familiar with her work, but I had never met Professor Menon,” says Meghwanshi. “I sent her a message requesting her to translate my book.”

At first, Menon was sceptical about taking up the project. She felt that a non-Dalit writer translating a book by a Dalit writer might be criticised. However, Navayana had already published an edition of B R Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste, with an introduction by Arundhati Roy, and it had been very well received.

“I also told Professor Menon that if any issues cropped up, we would fight it together,” says Meghawanshi. “She liked my message and agreed to translate my book.”

The translation did not provoke any controversy among Dalit intellectuals. On the contrary, it was very well received. French political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot, who studied electoral self-assertion by Dalits in his book India’s Silent Revolution, reviewed Meghwanshi’s book: “The book…enlightens the reader about the situation of the Scheduled Castes within the Sangh Parivar and in today’s Indian society at large.”

The need to write

Megwanshi believes it is necessary for people from oppressed communities to write about their experiences. He says that writing such accounts in the first person can be especially appealing. “A first-person account is more authentic and appeals to the masses,” he adds. “It is a simple way to connect with people. After reading your account, people will identify with your story and your message.”

This is not only a narrative strategy but also the need of the hour. “If you do not speak up now, whatever you might have said previously will be a waste,” says Meghwanshi.

A memoir is a particularly poignant genre, he adds. “Writers from oppressed castes and communities [such as Muslims] must write their memoirs. If they don’t, who will? One should not be shy about using the first person. Many people told me I was too young to write an autobiography. I said I was not going to wait till my death to write it. My experience with the RSS resonated with people,” says Meghwanshi.

Meghwanshi believes his book will inspire a lot of people to write about their experiences. He gives the example of Mool Chand Rana, another former member of the RSS, who founded an organisation for advocating Dalit rights, Samajik Samrasta Manch. “He is also writing about caste-based discrimination in the RSS,” says Meghwanshi. “It is now time to write our narrative.”

Meghwanshi was recently in Kashmir to meet Right to Information (RTI) activists.

“RSS produces a lot of literature about Kashmir. It has been going on for a long time. Kashmir, Kashmiri Pandits, and Article 370 are subjects dear to RSS leaflets, books, and newspapers,” he says. “I don’t think Kashmiris have written as much about the region as people from the RSS.”