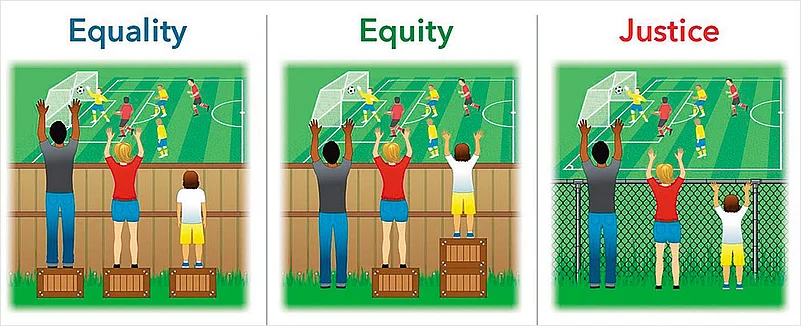

The equity approach distinguishes between equity and equality. The accompanying image best illustrates the equity approach, which is built around fairness and justice and factors in the contextual inequalities diverse groups of youth face. These inequalities pertain to caste, ethnicity, religious identity, gender, class, (dis)ability, geographic location, sexual orientation, and any other factor that may impact a young person’s well-being and opportunities.

Since these inequalities are structural and systemic, equity measures also need to be structural, focused on building relevant public institutions, effective public goods and services, adequate budget allocations and public education to create an enabling environment.

India has 37 crore people in the 15 to 19 age group, constituting 27% of its population. Of this, about 25% are from historically disadvantaged Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities, and about 19% are from religious minorities. The proportion of marginalised young people would be much higher if we included youth from the following groups: those with a disability, LGBTQIA+, nomadic and de-notified communities, migrants, slum or street habitats, and those living in areas affected by left-wing extremism, conflict or disasters. Young women from these communities face additional challenges of violence and patriarchal impositions. The intersection of various vexed factors further complicates the complexity of marginalisation and disadvantages.

We often adopt the ‘equality approach’ of providing services and resources in equal measure to all young people

In our desire to build a harmonious society, we often adopt the ‘equality approach’ of providing services and resources in equal measure to all young people. However, in most cases, young people from marginalised communities are unable to access or benefit from these services and resources. This anomaly widens the gap between marginalised and non-marginalised youth groups. What we, in fact, need is a well-modulated, nuanced and robust system to incorporate diversity, complexity and inequality while building equity measures. The task is daunting and needs urgent and immediate attention to prevent our youth population dividend from diving into a disaster.

Many rights legislations also include equity measures to address the specific challenges faced by marginalised communities – be it the SC-ST Prevention of Atrocities Act, The Forest Rights Act, POCSO, legislations related to violence against women in domestic and workplaces, or the RTE. The government has set up commissions and specialised agencies to oversee the framing and implementation of equity measures for marginalised communities. Population proportion budget allocations under the SC/ST plans facilitate the implementation of the equity measures.

Since these inequalities are structural and systemic, equity measures also need to be structural, focused on building relevant public institutions, effective public goods and services, adequate budget allocations and public education to create an enabling environment

However, sadly, behind the smokescreen of this robust legislative structure, implementation has floundered. Moreover, far from enhancing and expanding equity measures, some of them have, in fact, been rolled back. In the academic year 2022-23, the government discontinued pre-matric scholarships to SC, ST, OBC and Minority children in classes 1 to 8, stating that the Right to Education provides free and compulsory education till class 8. The national campaign on Dalit human rights consistently reports that mandated funds under SC and ST plans are being allocated to meet institutional costs and schemes that do not directly benefit individual members or the community.

According to data tabled in Parliament, between 2019 and 2022, funds for six scholarship schemes for religious minorities were reduced by 12.5%, and beneficiaries declined by 7%. The absence of adequate disaggregated data on the poor development indicators and their causative reasons further hampers the creation and implementation of equity measures. The government’s decision to omit disability-related data in the NFHS 6th round will make them even less visible.

India has a short window of time left to take advantage of its youth population dividend. The proportion of youth to the total population peaked in 2016 at 27.9% and is expected to decrease to 22.7% by the year 2036. Kerala and Tamil Nadu are already showing a downward trend. Notably, 52% of youth reside in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan, which are poor states with the greatest potential to create this dividend. However, it requires a “whole of society approach,” where the government, private sector, UN agencies, and civil society work together to forge a path forward in multi-dimensional indicators and multiple sectors. The youth, particularly those from marginalised sections, are invested in the process and hold the potential.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The author is Director, Centre for Social Equality and Inclusion