If the Mahabharata tantalises us with a female protagonist who has five husbands, then the Ramayana impresses with a male protagonist who looks at no other woman but his lawfully wedded wife. It almost seems that the two epics are talking to, and challenging, a society that has normalised monogamy for women and polygamy for men. Ram is described by poets as Eka-Bani (one who needs only one attempt with his bow to strike a target) and Eka-Vachani (one who always keeps his word) and Ekam-Patni-Vrata (one who is forever faithful to a single wife).

Marital fidelity is an important theme in the Ramayana, and this is foreshadowed by the very first tale we encounter when we are introduced to the epic. Valmiki, the poet-author of the epic, witnesses a hunter shooting down one of a pair of cranes. The surviving female mourns her loss with piteous cries that fills Valmiki with agony. It reminds him of Sita mourning her separation from Ram, Tara mourning the death of her husband, and Mandodari mourning the death of her husband, Ravana.

Tara remarries Vali’s younger brother, Sugriva, who then becomes king of Kishkinda. Mandodari remarries Ravana’s younger brother, Vibhishan, who then becomes king of Lanka. But Sita does not remarry. Nor does Ram. Remarriage is okay for the vanara (monkeys, forest-dwellers) and rakshasa (demons, barbarians?) but not for the Arya, followers of the Veda.

The Ramayana’s great plot twist comes after Shurpanakha seeks Ram’s hand in marriage. She is a rakshasa-woman. A widow, whose husband was accidentally killed by her brother, Ravana. Ram rejects her proposal. So does Ram’s brother, Lakshmana. Both argue they already have a wife. She does not understand. Surely men can have more than one wife. And she is a widow, free to marry others. Her way makes no sense to the Arya. When Dashrath, king of Ayodhya dies, no one expects any of his three widows to remarry. Not even the 21st century audience of the grand epic.

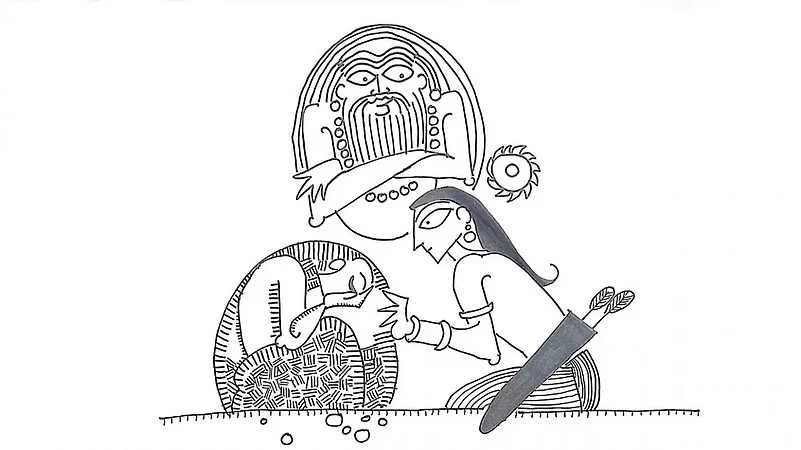

Ram is so faithful to his wife that in Andhra folk art, when he is shown fighting the rakshasa-woman Tadaka, his face is turned away from her, thereby informing viewers that Ram will only look upon the face of one woman —Sita. When he wanders in the forest, and women approach him and seek to marry him, such as the hermit-woman Vedavati, he politely declines. In some retellings, he promises to engage with them only in his next avatar when he becomes Krishna. These women are reborn as the milkmaids of Vrindavana and the many queens of Krishna in Dwarka.

During his forest exile, Sita is abducted by Ravana, who locks her up in his pleasure garden, Ashoka-vatika, on his island-fortress of Lanka. Sita is away from Ram through the rainy season. There are many stories, especially in Ramayana retellings, that are told to convince listeners that she could not possibly have been raped. First, that Ravana carried the ground on which Sita stood. Second, that Ravana was cursed by Nalakubera that if he touches any woman against her will, his head will burst into 1,000 pieces. Third, that Ravana was actually Sita’s father. Fourth, Ravana is unable to hurt Ram as he is protected by Sita’s power born of sexual fidelity, a power that belongs to faithful wives or the ‘sati’. Sita survives the trial by fire, proving beyond all doubt that she is pure in mind and body. Yet, there is public gossip. In later versions, the gossip is traced to a washerwoman—a symbolic character amplifying the fact that the gossip itself is a ‘stain’ on royal reputation and it cannot be ‘washed away.’

Sita’s story is foreshadowed by the tale of Ahalya we encounter in the very first chapter of the epic, when Vishwamitra takes Ram to the ashrama of Ahalya’s husband, Gautama. In early versions, Ahalya is simply invisible, atoning for her crime of infidelity, until Ram forgives her and renders her visible. In later versions, she is a rock, cursed by her husband, reanimated by the touch of Ram’s foot. Her lover, Indra, is cursed too. In early versions, he is castrated. In later versions, his body is covered with bleeding vaginas, which turn into blood-oozing sores, which turn into eyes. In early versions, she willingly accepts Indra as her lover. In later versions, she is a clueless innocent faithful wife tricked by the king of the gods.

In folk versions, found in Odisha and faraway Thailand, Ahalya and Gautama have three children—a daughter and two sons. When Gautama shows more love for the boys, the daughter reveals that the boys are Ahalya’s children born of Indra and Surya. Gautama curses the boys to turn into monkeys, who are named Vali and Sugriva. Ahalya then curses her daughter, Anjana, that she too will bear a monkey child, who is named Hanuman.

Whatever be the case, Ram is asked by Vishwamitra to rescue Ahalya, purify her, enable her reunion with her husband. Yet, in the final chapter, despite all evidence of her faithfulness (she never succumbs to Ravana) and her purity (Ravana does not force himself on her), Sita is abandoned. To make matters worse, she is pregnant. Her children are born and raised in the forest. Kusha and Lava sing the first Ramayana composed by Valmiki before him, like common entertainers. In fact, in Sanskrit, the word ‘kusha-lava’ refers to ‘lowborn’ itinerant musicians and storytellers.

At the time when Ram is marrying Sita, in Janak’s palace, he is challenged to a duel by Parashurama. We are told that Parashurama beheaded his own mother, Renuka, on his father Jamadagni’s order. Renuka’s crime was that she desired another man momentarily and lost her sati powers, reserved for women who are totally faithful to husbands. Later, Renuka is resurrected by Jamadagni on Parashurama’s appeal.

Renuka is polluted in thought. Ahalya is polluted in body. Sita is polluted in reputation. Clearly, fidelity matters to the epic storytellers. This is why the feminist movement has great discomfort with the Ramayana and the love poured on Ram by the political establishment.

That Ram does not remarry, that Ram places a golden effigy of Sita to represent his wife during his Ashwamedha Yagya is an important point. By virtue of being the eldest son of a royal family, Ram is forced to align with royal rules, and the patriarchal construct of his society, but by refusing to remarry he expresses his dissent. He turns out to be ultimately the surviving heartbroken bird, trapped in the cage by the hunter called raj-dharma, while his female mate is set free in the forest. But who bothers with such details in India’s greatest epic?

(Views expressed are personal)

Devdutt Pattanaik is the author of 50 books on mythology

(This appeared in the print as 'Faithful Husbands, Faithful Wives')